Я качался в далеком саду I rocked in a distant garden

На простой деревянной качели, On a simple wooden swing,

И высокие темные ели And tall dark firs

Вспоминаю в туманном бреду. I recall in a foggy delirium.

– Osip Mandelstam, 1908

Recently I arrived at the notion that to think (or to be) “on the left side of history” is a productive way to understand the problem of injustice. On the window of the café at my current place of work there is a taped A4 printed page that reads “permanently closed”. There is no doubt this is due to a lack of customers. It is inside the foyer of the Menzies Building at Monash University’s Clayton campus, which I estimated has about 600 offices, as well as meeting rooms, teaching spaces, and lecture theatres.

There is a small injustice here, I feel distressed for the operators of an isolated hospitality business. Is this history from below?

Or a history that is not concerned so much with its righteousness, but instead with the vicissitudes of the event—here easily ascribable to the Covid pandemic. Still, it is structurally the case that because all doors to the building remain locked, enterable only by swipe access, there is barely anyone inside their offices, let alone students in the classrooms and lecture theatres. Most people remain working remotely, and perhaps they will from now on. To dwell in this simple truth, perhaps, to yarn critically about this seems almost quaint. Not that this just popped itself into my head—I’ve been grappling with how to teach partisan histories in my class this semester. The time when academics would be apolitical in the classroom has seemingly passed, at least for now. I want my students to know what I think too, after all, whether we like it not, our history is presently ‘of the present’.

Indeed, it is history as a discipline, as a pedagogical concept even, that is at its lowest ebb when we run out of the present. We are told this, and feel it institutionally. But from beyond the university discourse it appears that more is at stake than ever for history and its related fields: federal governments are openly looking to re-establish the past after years of unmoored promises for the future. Former US President Trump’s 1776 Commission aimed at a ‘patriotic education,’ for example. Nostalgia is intoxicating older generations into strange fantasies of the significance of ‘the family,’ young people are reading and writing more than they have ever before. Publishers were not prepared for this, so they’ve had to write and publish a lot of their reading materials themselves, propelled no doubt by social media platforms and digitisation.

I am quite sure that these thoughts are one outcome from my time spent developing a unit called ‘ATS3394—Decolonisation: Past and Present’. I am teaching this curriculum within the same week as I am writing it, most weeks, throughout semester two of the academic year, and as a fixed-term lecturer on a 5-month contract at the School of Philosophy, History, and International Studies (SoPHIS) at Monash University’s Faculty of Arts. (The unit, a part of the History Department, is still in progress as I write this.)

The order of the school is written into its name, it seems: philosophy first, then history, then international studies (whatever that means). At an early-in-the-semester school meeting, followed by a discipline-level meeting (the interim Head of School is also a Historian), the word “evisceration” was politely banned from use at the school. It had previously been used to refer to the cuts recently made to the program’s offerings. Instead, we were asked to speak in more positive terms about the challenges that lie ahead (there is a new Dean of Arts at Monash, a Historian!) At the end of the meeting, the (interim) head of the History Department announced his retirement.

The fact of my contingent appearance as a teacher at the school (I have worked casually at the Monash Art Design and Architecture Faculty, MADA, since 2017), and the really random request that I write and teach a unit—as a non-Indigenous person with a doctorate in Art History—that is listed on the handbook, and apparently already with 100 enthusiastic students enrolled and ready to decolonise everything, seemed to confirm in my mind at least what is obvious if you take the sector’s cries at its word: there is a crisis at our tertiary education institutions so deep that it appears existential.

The academics who had cried wolf, I imagined, didn’t really have a mouth left to call from when the shit actually did hit the fan—the Covid pandemic should have toppled the institutions, one professor told me, surprised that it hadn’t really worked out that way. They are so hollowed out and reliant on international student income, so the argument goes, that they only needed the slightest change in the wind to fall over. The empty Menzies Building seems to accord with this theory. Yet Zoom, and boredom with lockdowns perhaps, weren’t figured into this equation—which was aimed more at management than anything key to the operations of the university, like teaching or research.

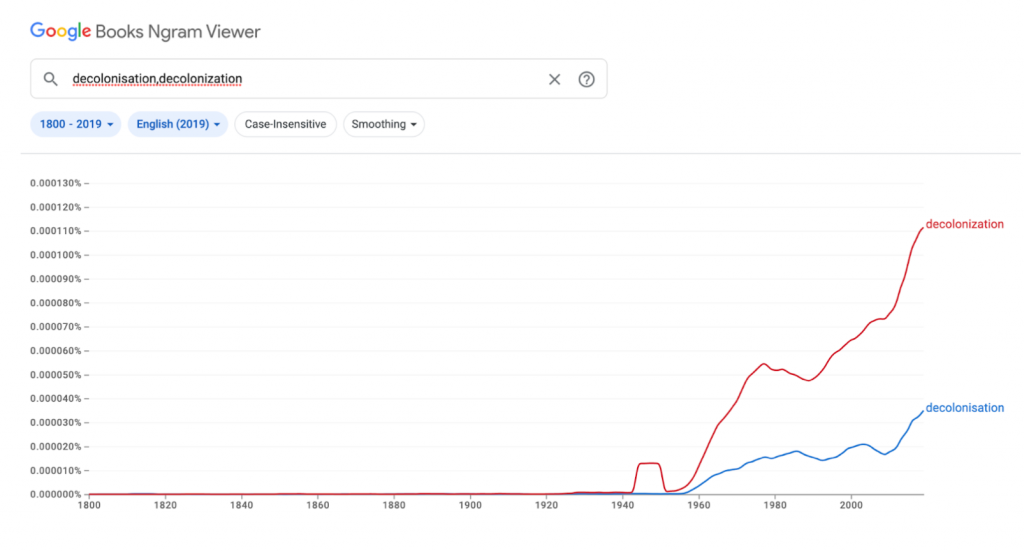

Regardless, by taking on the assignment to teach decolonisation I now had too much work to do. None of the First Nations academics already working at Monash University would talk to me about decolonisation. Fair enough, I thought, my task was to define a term that has had its meaning relentlessly evacuated, as corporate jargon takes over any term that has experienced a steep enough upward trajectory (fig. 1). But I vowed to talk about the ‘past’ as events related to the structures of settler-colonialism and the ‘present’ as unsettled debates currently pressing in on the calving continent of so-called Australia. When I spoke with Gary Foley about decolonisation, his response was posed in the way he thought Paul Coe may have put it: ‘the question is really what are you doing teaching this subject? It should be taught by a colonised person. It’s a bit—here is a word I learnt when studying at university—“problematic” isn’t it?’

Fig. 1 Google Books Ngram Viewer search for the terms decolonisation & decolonization.

And then I read Chelsea Watego’s Another Day in the Colony. As an academic that had blown the whistle on racism at the institution, her work was like dynamite for the sandstone blocks and manicured grounds of the Academy. Further, as a member of the National Tertiary Education Union, and now a National Councillor for the Union, I felt a deep sense of embarrassment and frustration that its Industrial Officers and Executives had calculated it was not willing to support Watego, a member, through a race and sex discrimination complaint taken against her employer, the University of Queensland.

Appreciating this read? Be sure to CHIP IN to help fund future articles from Green Agenda.

I’m reading Watego’s account of ‘walking away’ from her workplace with students for the Decolonisation unit, and at a moment when the idea of work in Australia seems to be in danger of a reduction to the (simple) equation: ‘do what you hate,’ for money. Meanwhile, jobs the world over are becoming increasingly useless (as argued by the late David Graeber), and people in (predominantly) white-collar jobs are now considered to be ‘quiet-quitting’ if they only attend work is to collect a pay-check. They’ve lost any belief they had in the meaning of their work. So what we are seeing is the effects of what philosophers of technics, like Bernard Stiegler, had foreseen in the drive towards an ‘automatic society’: mass proletarianisation.

Coincidentally, I had written about hopeless labour late in 2021 when thinking about my time at my last employer, the University of Melbourne. I’ve since received back pay of over $10k through rolling wage-theft investigations. I was struggling with the idea that we might be responsible for having exploited ourselves through hope. Drake and Future ‘rap about the one-hundred thousand dollar rings they’re now wearing on their ‘cheapest’ fingers.’ I wrote out the line: “Hope is a lil’ bitch.” Future mumbles and it reminds me of a paradoxical aphorism offered by the high priest of the age of mechanical reproduction, Walter Benjamin: ‘Hope is for the hopeless.’ In other words, it is an ideological tautology, like a ring.

In the final chapter of Another Day in the Colony, Watego continually, unceasingly claims ‘Fuck Hope’:

Hope is a most ridiculous strategy for Blackfullas in the colony precisely because it doesn’t actually do anything – for us. It relies upon a false sense of respite from the reality of everyday racial violence in the colony; that we suspend all logic and cling to hope, a waiting for a future good while living in a permanent hell. It tells us to wait, that one day we will get our turn. It tells us that we aren’t worth fighting for right now, but what it doesn’t tell us is that day never actually arrives. Hope is a suspension of Black trauma in the midst of Black trauma, and a premature death sentence for those destined to be betrayed by it (Watego, 2021, p. 197).

On Twitter I see a conversation about the distinction that must be made between exploitation and oppression. Blak Australia is oppressed. The word hope, in its English usage, can be traced to the 12th century. In its Old English usage, it pertains to a “confidence in the future”. In the King James translation of the Bible in the early 17th century, Romans 4:18 is rendered into English in the following way:

Who against hope believed in hope, that he might become the father of many nations according to that which was spoken, So shall thy seed be.

Against all hope, Abraham had hope, and so became the father of many nations. As such it appears closest to faith. Paul’s epistle was written in the context of Hellenization, which we know today by the concept of assimilation. That is, Paul’s apostolic treatise is concerned both with the Christian mission and with colonisation. Therefore, the ancient idea of hope was directed against itself in faith towards the mutual establishment of both peoples and nations, specifically the Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

The powerful mix of Blak pessimism, of hopelessness in the face of what Watego terms—through her conversations with Gangalu woman Dr Lilla Watson—’colonial settlerism,’ coupled with an active nihilism that is about permitting an emancipatory logic to enter spaces otherwise dominated by white supremacy, aims at sovereignty. It is this structure—the one that allows the late Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II to be characterised by some loyalists as a sovereign who ‘worked to serve her people for every minute of her life’—that shows what it might mean to be unalienated from majesty. When we repeat the call: ‘sovereignty was never ceded,’ there is more than a symbolic notion that is at stake. It is the ‘unmitigated Blackness’ that Watego identifies, that snatches back at this idea of majesty, precisely by targeting the shibboleth of hope. Importantly, it starts by abandoning hope at the tertiary institutions. Their emptiness is hopeless, the effect is deliberate.

Over ten years ago now I started a blog using a quote from a Thomas Pynchon novel and titled it ‘out and down in the colonies’. The first image I’d uploaded was taken from the window of a cheap apartment in Mitte I’d found on Craigslist, looking down into a snow-covered construction site at the centre of Berlin. At the time I didn’t dare think about the work I could do concerning sovereignty. If collectivity was the problem, the answer was more collectivity. So I thought about sovereignty in the sense I’d gleaned from Giorgio Agamben, who in turn was reading Carl Schmitt and not thinking that far beyond the porous borders of Europe as an ideal for civilisation. Instead, as I realise only now, Pynchon had already held up this mirror to my colonial settlerism in 1973:

Colonies are much, much more. Colonies are the outhouses of the European soul, where a fellow can let his pants down and relax, enjoy the smell of his own shit. Where he can fall on his slender prey roaring as loud as he feels like, and guzzle her blood with open joy. Eh? Where he can just wallow and rut and let himself go in a softness, a receptive darkness of limbs, of hair as woolly as the hair on his own forbidden genitals. Where the poppy, and cannabis and coca grow full and green, and not to the colors and style of death, as do ergot and agaric, the blight and fungus native to Europe. Christian Europe was always death, Karl, death and repression. Out and down in the colonies, life can be indulged, life and sensuality in all its forms, with no harm done to the Metropolis, nothing to soil those cathedrals, white marble statues, noble thoughts… No word ever gets back. The silences down here are vast enough to absorb all behavior, no matter how dirty, how animal it gets… (Pynchon, 1973).

What we need now, if it is not clear, is a truer history of the present. Not silence, but hope against hope, to catch a fire.

Abbotsford, September 2022

If you appreciated the read, be sure to CHIP IN, even as little as $5, to help fund future articles.

Giles Fielke is a Lecturer at SoPHIS in the Faculty of Arts, Monash University. He is an editor of Index Journal and Memo Review. He is also a filmmaker and his most recent film, The Gardens (2022), made with Paddy Hay, was selected for the 11th Antenna Documentary Film Festival.

Image Credit

Feature image, Pipes by Dean Hochman.