Tani Walker’s superb voice resonates around the crowded Freo Social venue. Head thrown back, she sings of the Noongar season of Bunuru (February to March) and a hope for relief from the Western Australian heat. She is part of Richard Walley’s Six Seasons, a series of songs each celebrating the Noongar seasons of Birak, Bunuru, Djeran, Makuru, Djilba and Kambarang. Tani shares the crowded stage with vocalists Natasha Eldridge, MC Flewnt, and Joel Davis with Richard Walley playing didgeridoo. The fantastic Junkadelic Collective accompany them, filling the hall with big sounds and funky rhythms.

This musical event was the headline act for the BRINK Festival which happened in March this year. I was a co-founder and producer of BRINK, the short festival that grew out of protests around how the Arts are funded in WA. We aimed to offer local artists an alternative to the Woodside-funded Fringe World so they could create work in a way that supports their values, instead of having to compromise them.

And artists are struggling, in more ways than one. It’s tough out there.

During the COVID pandemic, when it came to supporting precarious workers, many artists were either deliberately forgotten or casually overlooked when it came to government support. Whilst salaried workers in arts organisations may have received JobKeeper, many individual artists were left to survive as best they could.

What’s new, you might ask? Haven’t artists always struggled? Yes, there’s very little money in the Arts, and this seriously needs to be addressed. But that romantic image of a noble artist in their garret is annoyingly persistent. Arts funding has been in decline over many decades as planet- and society-destroying, neo-liberal economics have become the “norm”.

This financial hardship is driving artists towards making profoundly disturbing choices. It’s affecting their well-being; it’s allowing dubious behaviour and practices to occur; and causing many exceptionally creative people to leave the profession for good. To survive in the Arts today means to conform, to play nice and stay quiet, to be part of a funding arrangement that serves the interests of private entities and less and less the interests of the public at large. Unless one is lucky and privileged enough to have a private income, artists must face the consequences of these pressures and wrestle with another, and perhaps more disturbing, crisis: their very legitimacy.

Many artists see their work as more than merely a product. It’s part of their identity. They literally put their bodies, philosophy, and emotions into the public space. They can be our social conscience and ask the hard questions, they help us wrangle with context and issues. And as we admire them for their creative talent, we can also imagine and explore our own concerns, emotions, fears. Art helps us question, learn, imagine, dream. Art can change us.

Whilst the BRINK Festival in no way solved the dire situation many artists find themselves in, it was a small, artist-led attempt to take back our power as creative workers. It was a response to how art and artists are seen increasingly as a commodity to be exploited in the cause of something else, usually big business or a sector like tourism. This lack of direct support for the Arts can be seen more clearly when we look at the economics of art making.

The number on Arts

The independent think tank, A New Approach, states in its 2019 report The Big Picture: Public Expenditure On Artistic, Cultural And Creative Activity In Australia that

“Australia’s federal, state and territory, and local governments together currently commit more than $6.86 billion of public funds to arts and culture each year, which is approximately 1.0 per cent of the combined total expenditure made across all levels of government.”

This figure is based on an estimate from government and Australian Bureau of Statistics figures and refers to in 2017-2018 financial year. Since then, along with COVID, even further cuts have occurred.

Compare this to the billions in subsidies given by the Commonwealth to the fossil fuel industry, which The Australia Institute (TAI) states was $10.3 billion for 2020-2021.

In addition, another recent report from TAI, Creativity in Crisis, makes an excellent case for the dollar value that the Arts contribute to GDP, the large number of jobs artistic activity creates, and how, with more support, the sector can be an on-going economic driver. The oil and gas creates 0.25 jobs per $1 million turnover, just a fraction of the 6 jobs per $1 million created by those working in arts and entertainment sector (p.13).

However, the report also outlines how the Arts sector has fallen victim to the ‘market first’ ideology of successive governments. Arts spending as a percentage of Australian GDP now places us 24th out of 33 OECD countries.

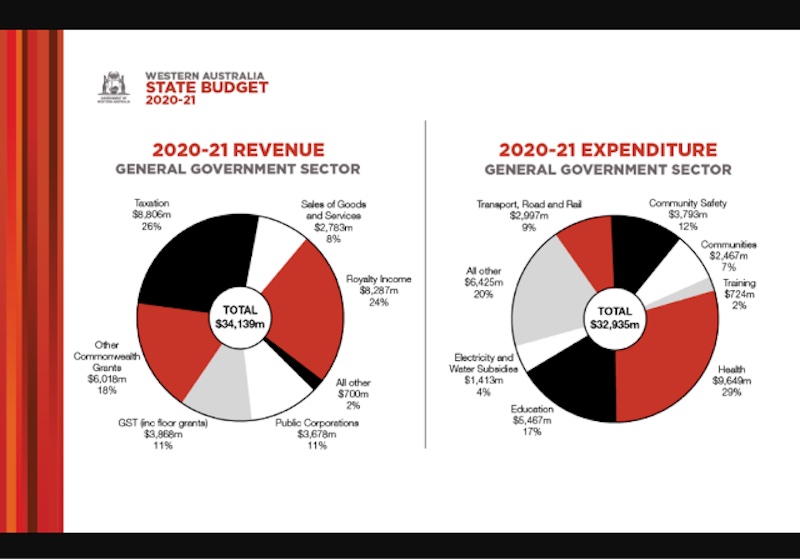

It is often hard to even find these figures in the fancy pie charts showing government spending created for public consumption. For example, in the one below from Western Australia’s 2020-2021 budget, Arts and Culture are not even big enough to mention, and it’s lumped into the “other spending” category.

Arts amid capitalism

There’s a danger in only valuing the Arts within the essentialist framework of the capitalist, neo-liberal economy. This tends to diminish the community good of examining our lives through shared experiences, through story-telling and emotional connections. So, it’s significant that the TAI report also makes a pitch for us to “recentre arts and culture as a public good: affordable, accessible and participatory.”

There are very few artists who can claim to be working full-time in the sector. Most go from project to project and grant to grant, supplementing their income with teaching or through other, often non-arts-related, casual work. Money is scarce. Over the years, to make up for declining government support, and to cover ever-rising costs, many arts organisations have sought support from individual philanthropists, philanthropic foundations, and corporate sponsors.

Philanthropy, or the tradition of returning wealth to “good causes” through donations, does not appear to resonate too well with most people in Australia. Creative Partnerships CEO, Fiona Menzies stated in 2020

“not everybody feels that the arts and culture are worthy of philanthropic support, compared to other cause areas. Sometimes this is just a sense that I get, but at other times people are openly critical, even hostile, about the arts receiving philanthropic funds.”

As a society, we value welfare safety nets that provide collective support for the elderly, the disadvantaged, the unemployed and the sick. When artists per se are not seen as falling into those categories, then why should they be given a hand-out? So the thinking goes.

Even small, community-based arts organisations are feeling the pressure. Meridian Regional Arts Inc. in Merredin WA, worked hard to receive a Lotterywest grant as part of a COVID relief package this year. However, they still felt that had to make a statement to justify their good fortune:

“The arts isn’t a waste of money. It is a vital contributor to the Australian economy and turns the small amount of money invested into it into real economic gains for communities.

There are going to be people who have their feathers ruffled by arts projects happening in town, and if that is you, if you feel frustrated by the idea of the arts, know that by it happening here there is a good chance there will be positive gains for the community…

The money for this project has not been taken out of the Merredin Shire Budget. This money will not reduce the amount of money that is spent on hospitals or roads or education. But we hope it can do some good here.”

When it comes to philanthropy, of the donations that have attributions, many come from the rich and the super-wealthy, and this fact should be driving any argument about art as a public good. Without open and transparent funding processes, art may become a private good. It will be used to ‘art-wash’ corporate images and boost the egos of millionaires and billionaires desperate to create a ‘legacy’. Even worse, it could have the effect of silencing criticism of the powerful through art, or worse, that the Arts become tools to promote propaganda.

Appreciating this read? Be sure to CHIP IN to help fund future articles from Green Agenda.

Funding, propaganda, and conformity

Going too far? Not really. History shows that with the rise of any authoritarian regime, the artists, writers, poets, stars of stage and screen, are the first to be ‘re-educated’. This is why PEN and similar organisations exist. Why Amnesty International frequently calls for the release of imprisoned artists and intellectuals, alongside political activists. For many years I’ve worked with and supported an artist who is in exile from a dictatorship. He was imprisoned and tortured multiple times for writing poetry and plays. He has experienced first-hand the fear of a dictator who understands the power of art to move people; how it can help them reflect on their society and culture and give them the courage to resist their oppression. Even Plato was wary of the poets.

In Australia we don’t yet have an authoritarian regime, nor do we routinely imprison artists, we just need to starve them of funding until they conform. The cost of creating art has become so high that seeking extra, private funds is now a necessity. The price of materials, venue hire costs for both performance and gallery spaces, publicity costs, etc. are only part of this calculation. Most full-time paid work in the arts is not given to practicing artists but to the structures that support an arts bureaucracy. These salaried positions are expected to be in place so that arts organisations can gain acceptance from government funding agencies, philanthropists, and corporate sponsors. Alongside this, the often excessively high administrative compliance demanded – increasing governance requirements, extensive grant applications, drawn-out acquittal processes, commissioning of consultants to write reports to gain legitimacy, and so on – takes up a significant amount of that paid staff’s working day. No artists are offered similar salaried positions to make creative work.

But what if philanthropy is too hard to achieve? Or, more importantly, if the individual or foundation offering it doesn’t align with your values? This latter question is one that artists and arts organisation with any form of ethical framework must ask. Would you take money from a known sexual abuser, or someone who is racist, or who from a family that made their fortune from exploiting First Nations peoples and their lands?

No? So, without generating sufficient income, or having your own or a kind auntie’s resources, that leaves corporate sponsorship. This has become an increasingly important revenue source for arts organisations. The extent of this can only be surmised from the logos on websites and in the pages of event programmes. It’s very hard to find out exactly how much corporations give to arts organisations. Unlike political donations, most of these arrangements are carried out in secret. Even if an arts organisation also receives substantial funds from all levels of government, sponsorship deals are considered “commercial in confidence” arrangements. The public accounts of arts organisations are minimal at best, but they lump together their income into indecipherable line items with no real transparency.

This practice is further complicated by the personal involvement of employees from the very same sponsoring corporations. Over the years, many arts boards, particularly those of the major companies, have included employees from the fossil fuel and mining industries. Gabrielle di Vietri articulates this extremely well in her artwork Maps of Gratitude, Cones of Silence and Lumps of Coal (2019).

Despite the best efforts of many sponsors to label themselves as “good corporate citizens”, their sponsorship is not value neutral. These corporate individuals may generously introduce desperate arts development managers to the so-called ‘community engagement’ department in their commercial workplaces. And, being on the board, they can keep a close eye on how and where the money is spent. Referring to sponsorship as ‘community engagement’ is Orwellian double-speak at its finest.

For artists with a strong ethical backbone, the only act of free will left is to refuse this money. But that’s easier said than done. When artists questioned the sponsorship of the 2014 Sydney Biennale by Transfield (a supplier to Australia’s off-shore detention centres), they provoked a government backlash. An initial statement from the Biennale itself seemed to imply that artists can only be involved if they support the “understandings and beliefs” of the board, who unequivocally supported the sponsors. What about the understandings and beliefs of the artists themselves? They seem to have become irrelevant.

However, when the Biennale eventually severed ties with Transfield, then Attorney-General, George Brandis, threatened to withdraw commonwealth funding from organisations that refuse corporate funding on what he said was “unreasonable grounds”. Malcolm Turnbull went even further calling it “vicious ingratitude”. Brandis then diverted a large percentage of Australia Council funding to what was little more than a slush fund for the arts organisations he preferred.

Taking an ethical stance has become a dangerous endeavour. But what are the alternatives left to artists? In a resources heavy state like WA, there are not many. Or if there are ethical funding sources, they don’t appear to engage with the arts. It’s a stark choice between creating work for little or no payment as an act of moral integrity or compromising one’s morals and ‘working for the man’.

In recent years, taking sponsorship from fossil fuel corporations has become a necessary choice for many arts organisations. However, corporate interests using the arts is nothing new. In the 1995 book Free Exchange, Professor of Sociology, Pierre Bourdieu and prominent visual artist, Hans Haacke make an important point that this funding provides powerful symbolism; this support can be portrayed as the “disinterested generosity of the corporations.” But these donations are far from our traditional understanding of patronage. They verge on public relations exercises, with artists as the losers, caught up as de facto employees in a cynical marketing exercise. Bourdieu and Haacke also warned how “private patronage may justify the abdication of public authorities… to withdraw and suspend their assistance.” With the reduction in support for the Arts, this justification may already be underway. Furthermore, they suggest that these private funds still end up being paid for by the public, as it may result in the loss of government revenue if they are used as a tax deduction.

On silencing and gag orders

This also goes beyond dollars. When fossil fuel corporations include in their contracts with arts organisations so-called ‘gag orders’, then the very purpose of Art as a public good is shattered. The Woodside-sponsored Fringe World in Perth added such a clause to their 2021 application form. It stated:

“The PRESENTER and the VENUE OPERATOR must use its best endeavours to not do any act or omit to do any act that would prejudice any of FRINGE WORLD’s sponsorship arrangements…

If you have an objection to a FRINGE WORLD sponsor, we ask that you consider whether participation in the Festival is the right platform for your presentation.”

The consequence of ‘prejudicing’ a sponsor is not stated, nor is it clear if any is possible. After all, Fringe World is an open access festival with artists taking the financial risk when participating. Nonetheless, the intention is clear: if you rock the boat, then you’re not welcome here. That fear of exclusion leads to self-censorship. After all, the arts industry is built almost entirely on professional working relationships and anyone disrupting the norm and upsetting the gatekeepers will risk being shut out. As Tom Ballard said in an article for The Guardian “If we don’t have artistic freedom, the chance to say what we want in those shows because of the commercial arrangements surrounding the festival, then I think we’re in really dicey territory, particularly now we’re really getting towards the crunch time with the climate crisis.”

Art sponsorship has become a tool for the seduction of a vulnerable public by commercial interests. But the public’s opinion does matter more than they may realise. If citizens speak out loudly and forcefully enough, opposing the damaging consequences of extracting and burning fossil fuels, then governments might just pay attention. But if they can be soothed into benign indifference or even worse apathy, then all hope for positive change is lost. Art-washing works, and business as usual continues.

Woodside has been sponsoring the Western Australian Youth Orchestra for three decades. At the start of this relationship, fossil fuel companies knew about the future impact of increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from their operations. In fact, many of them even commissioned scientists to do this same research. For thirty years, Woodside has been purchasing a social licence to operate using the very children and young people who will be most affected by the climate crisis. Many of them hadn’t even been born when this strategy was first enacted. Was it the company’s long-term intention to bank public goodwill in a cynical attempt to delay or deflect meaningful action on climate change? Was supporting children pursuing their dreams to play music seen as an effective ‘community good’ dressed up as art wash? As more and more artists, audience members, scientists and parents of aspiring artists, wake up to the climate crisis and its causes, they are also becoming aware of their tactics of deny, deflect and delay. These have been used by fossil fuel interests over the past forty years and increasingly are being exposed. Things are starting to change.

Pushing back

There has been pushback against these fossil fuel sponsorships. And some successes. Over the years, the disquiet and dissent amongst artists globally has grown. Campaigns by multiple groups, such as Art Not Oil, Reclaim Shakespeare Company, Liberate Tate, Artists against Fracking, Culture Unstained, and others, have managed to convince leading arts and cultural organisations to end their cosy deals with fossil fuel companies, many of which had been in existence for decades. In Australia, independent artists and concerned audience members are fighting back. From letter writing, to protests, to creative protest actions, they’re showing their opposition to business as usual.

One event that publicly stated early on that they will not accept sponsorship from fossil fuel corporations was Revelation Film Festival in Western Australia, affectionately known as Rev. The director, Richard Sowada, says he’s always been active in the areas of social and environmental justice, and Rev aligns with his values. However, it’s not been an easy ride.

After an article published in 2020, he experienced a backlash from funding bodies and arts administrators. Multiple comments on social media seemed to echo Malcolm Turnbull’s view on ingratitude or accused him of naivety, implying that this was how things were, and there’s no changing it.

Even as more artists question funding sources, no one in the film sector has publicly applauded Rev’s long-standing ethical position. But Sowada is not dissuaded. Arts organisations need to get their ethical frameworks in place, and as he says, “Climate change has been around for a very long time. The world has changed. The arts need to transition from what they are to what they need to be.” Rev is undergoing a full carbon footprint audit and will be integrating environmental and social justice performance indicators into their planning. He recognises that this is increasingly being demanded by audiences and artists alike. “We’ve survived because we’ve been open to change.”

It seems that fossil fuel corporations are still trying to hang on to their association with the Arts even as it is starting to look shaky. There appears to be a shift away from visibly ‘branding’ themselves as supporters of the arts as bluntly as they did before.

After protests and publicity about artists not being happy with the sponsorship, Chevron, a long-time supporter of Perth Festival, appears to have shifted gear. In past years, a unique venue has variously been billed as the ‘Chevron Gardens’ and the ‘Chevron Lighthouse’. In 2021, Chevron was only listed as a ‘community partner’ in the festival’s brochure, without it being clear what that really means.

For two years, artists protested at Fringe World Festival. In 2020, they stormed the stage on opening night, calling for an end to Woodside’s sponsorship. Many local artists joined with Extinction Rebellion WA to protest the prominence of Woodside branding throughout the festival by reading extracts from the 5th IPCC report outside the popular Woodside Pleasure Gardens. This fenced off area of tented venues, food trucks, bars and portable toilets, situated in Russell Square in the heart of the nightlife suburb of Northbridge and has come to symbolise the festival’s identity .

Again in 2021, activism was prominent. The ‘Gag Enforcers’ greeted patrons at the ‘Woodside Pleasure Gardens’. These Enforcers used comedy to ensure everyone complied with the gag order and said nothing that might adversely affect the event’s sponsors. A video was also projected onto a nearby building showing the Australian bushfires and linking the causes to the very fossil fuels Woodside extracts and sells.

Appreciating this read? Be sure to CHIP IN to help fund future articles from Green Agenda.

After several other actions and an ‘Ask Me Anything’ with Sharon Burgess, CEO of Artage, the producer of Fringeworld, it was announced in July this year that Woodside will no longer have the naming rights to the Pleasure Gardens. On the surface these seemed like a step in the right direction and was greeted positively by artists.

Noemie Huttner-Koros, a co-founder of the Arts and Cultural Workers for Climate Action group, said in an article:

“… It has not been acceptable for me and many other artists to perform whilst simultaneously promoting a company committed to new fossil gas production… I’d like to thank the Artrage chief executive and board for making this decision. I and many others look forward to returning to the first post-Woodside FringeWorld in 2022 and continuing these vital conversations about climate justice and the arts.”

However, it appears that Artrage will still be taking Woodside’s sponsorship, but it is as yet unclear if this is a transition agreement to move them away from their relationship with Woodside, or just a retreat to take the steam out of further protests.

But what are the alternatives?

Arts organisations find it very hard to divest from this easily given fossil fuel money. Here in WA, the chance of finding other local sponsors seems very limited. Rio Tinto, whilst not a fossil fuel company, seems poised to further develop its ‘community engagement’. It funds CineFest Oz the annual film event in Busselton, WA. Many aspiring filmmakers hoping for exposure, find their work is relegated to screens in hotel foyers or as backdrops to lavish drinks events as corporate executives smooze with celebrities. But it’s a great boost for the local tourism industry and realtors though, just less so for the Arts.

Rio Tinto has a poor record when it comes to protecting First Nations heritage at home, for example, Juukan Gorge, and basic human rights overseas. It was recently awarded the Cane Toad Award by Friends of the Earth Australia for its activities in Bougainville, Solomon Islands. Alongside them, the Minderoo Foundation is sponsoring more and more creative events, as well as funding individual artists up to $25,000 each to directly to make work. This foundation is a family affair for Andrew Forrest, a man who has had various business interests from iron ore mining, uranium licences, the Port Kembla LNG facility, the development of hydrogen as a fuel, and he advocated and lobbied for the cashless welfare card. Co-chaired by Forrest and his wife, Nicola, his daughter Grace is also on the board, along with Andrew Liveris, a director of Saudi oil giant, Saudi Aramco.

As di Veitri notes in her video, many of the other sponsors of creative work and board members in arts organisations are connected in some way to the fossil fuel and mining industries including those that provide financial services or infrastructure support. But do we really need their money? Is the only way to be accepted as a ‘real’ artist through large-scale productions and a lanyard to give access to the inner sanctum of the major arts institutions? Indeed, have these grand gestures become merely symbolic? Going back to Bourdieu and Haacke, they see sponsorship of the Arts as a form of capital exchange: financial capital for the symbolic capital of art. They quote corporate sponsor, Alain-Dominque Perrin from Cartier, who says ‘[patronage] is a tool for the seduction of public opinion’. Perhaps the tax breaks received from such exchanges would be more accurately be called “tax seductions”.

If businesses engage with artists, arts organisations, or events, then some of Arts inherent authenticity will rub off onto them, their practices and products. The Arts are seen as merely a proxy for selling stuff better. But does it have to be this way?

Just as the transition away from fossil fuelled energy will take innovative thinking and a novel approach to energy delivery, use and reduction, so how we fund the Arts will require a new approach. Replacing one corporate sponsor for another with a less egregious business model is not enough. We need to rethink how and why we make and present our Arts so it can continue to be relevant and hold a valued place in the lives of our communities.

The BRINK Festival was a defiant attempt to contest fossil fuel sponsorship, but also a way for artists to work with dignity and according to their personal values. Yes, it was a small affair, featuring only ten events, but it was achieved and produced in less than five months with only a small local government grant as initial funding. Perhaps this is the way forward: high-quality, small-scale events that reflect communities and are made for and with them; real creative engagements that ask difficult questions, that tease out complexity and moral dilemmas; small scale symbols of resistance.

Practical steps to reduce carbon emissions is one way forward to lessen the impact of making art. The Sydney Theatre Company launched their Greening the Wharf project in 2007. Green Music Australia want to turn the music industry green, through waste reduction and carbon offsets, and to ‘become the cultural voice for inclusive environmental change’. It is essential that arts organisations take these steps as well as divest themselves from fossil fuel sponsorship in order to really gain credibility for their actions. However, at the heart of any support for the arts is a recognition of its value to society, how it is a public good.

The European Parliament understands that ‘Cultural activity has an economic as well as a social and mental health dimension, which is particularly important during the period of measures against coronavirus.’ Several countries have announced important support measures and indemnities for artists and arts organisations since March 2020.

Systems that financially support individual artists exist in other countries. France has a special unemployment insurance scheme for ‘intermittents du spectacle’ or unemployed arts workers. They receive a monthly stipend from the state providing they work a certain number of hours over a 12-month period. In Germany arts funding applications have the same status as job applications for unemployed artists, who are also covered by a specific social insurance system.

The Australian Greens recognise that artists play ‘an essential role in our nation’s cultural life and identity’. Our Arts and Culture policy calls for the introduction of a fixed income support scheme for artists, and for a range of other supports to ensure artistic and cultural experiences are available to everyone. Art is more than a playground for rich philanthropists or a means for corporate art washing. It belongs to all of us.

As the activist organisation Oil Free Sponsorship states:

“If we remove the cultural power of fossil fuels, we undermine the political, financial, and diplomatic support companies like BP and Shell desperately need to continue drilling ever deeper.

Fossil-fuelled culture makes it difficult to imagine not using any oil or gas. And by refusing association with fossil fuels we are enabling alternatives to flourish.”

Back in the cavernous hall at Freo Social, Richard Walley’s Six Seasons, draws to a close. The performers leave the stage to rapturous applause, and the thrill of their songs reverberates in the hearts and minds of everyone present. This performance was a celebration of our place in the world – the South-Western corner of Australia – and the knowledge and culture that has existed here for tens of thousands of years. As a country and as a society we need to recognise that First Nations People are still waiting for justice. The environmental destruction and social injustice carried out during the extraction of fossil fuels and other resources occurs on their traditional country. Sponsorship is not only used to buy a social licence to operate in the Arts, but it is also prevalent within these affected communities.

BRINK Festival, the creative protests, rallies, letter-writing, advocacy and lobbying are all part of a push-back, a way to begin these important and necessary conversations: how can we have an ethically, sustainable Arts and Cultural sector free from corporations damaging our climate? One that cares about country, about artists and about our children’s futures? One that empowers artists and gives them ethical options to practice their craft?

Artists want the freedom to create work that aligns with their values and their sense of identity. Is that really too much to ask?

Reference

Free Exchange (English translation), Bourdieu, Pierre and Haacke, Hans; Polity Press, 1995, (Cambridge, UK) ISBN 0-7456-1522-8

Further reading

‘Using Art to Render Authenticity in Business’, James H. Gilmore & B. Joseph Pine II, In: MERMIRI, T. (ed.) Beyond experience: culture, consumer & brand, Arts & Business, 2009, (London, UK)

Vivienne Glance is a writer, performer, reviewer, arts and environmental activist and has created work and produced events, including BRINK Festival, that address the climate crisis and other important issues of our times. (https://www.vivienneglance.com). She is a member of the Fossil Fuel Free Arts Network (FFFAN).

One thought on “The Art of Greenwashing: (De)funding creativity and silencing dissent”