COVID-19 has thrown Australia’s university sector into crisis. For the past two decades, the tertiary education industry has expanded on the back of rising international student enrolments. However, the coronavirus pandemic, and the resultant border closures, have disconnected universities from these enrolments, one of their most significant revenue streams. Universities have been hard hit: Job losses have already commenced as casuals and fixed-term employees have been told their contracts will not be renewed, and forced redundancies are slated for those campuses most dependent on foreign student revenue. Unsurprisingly, the forecast revenue crunch and lay-offs have fuelled pessimistic analysis about the future of higher education in Australia.

Yet I will argue in this piece that the pandemic presents a thin silver lining for the sector. University job losses have helped draw significant media attention to the pernicious practice of employing casuals to shoulder the increased burden of teaching more students without satisfactory remuneration and workplace rights. It presents universities with a chance to reflect on this trend. It is this relatively opaque employment practice that I will examine in this article by reflecting on my journey through casual academia.

Although casualisation pervades all of Australia’s higher education providers, my story will centre on the Australian National University (ANU) – not because ANU is the worst offender. It isn’t. But my experience as an ANU casual academic over close to a decade can help shed light on how structural wage theft can become a business-as-usual strategy at one of Australia’s leading research universities, and how the inequitable treatment of casuals can become normalised within the corridors of institutions that pride themselves on calling out injustice.

Personally, the present pandemic, and the damage that it has wrought on universities, has forced me to reflect deeply on my experience as a cog in the academic machine. Although I thankfully managed to secure a fixed-term contract in the middle of a global pandemic and economic downturn, the experience of working at the coalface of casual teaching has indelibly impressed upon me the unjust nature of this employment practice. This reflection has also allowed me to further understand the institutional and economic logic behind the Australian university sector’s increasing dependence on sessional academics. In an increasingly unfavourable research funding environment prompted partly by government policy shifts, this economically profitable practice cross-subsidises research activities and benefits high-salaried tenured and fixed-term academics whose KPIs are primarily centred on research grants and publications, not teaching. Moreover, the sector has priced casual academic labour incorrectly through irrational pay rates (and associated workloads) which it has enshrined in enterprise bargaining agreements, thus resulting in the market failure of too many (exploited) casuals and a needlessly larger academic workforce.

My Experience of Casual Academia Before the Pandemic

My casual convening story starts in June 2016 while I was in the midst of my seemingly never-ending PhD thesis on Chinese environmental policy reform. Back then, my Head of School offered me a casual academic contract to teach one of our School’s more significant later-year courses. I had tutored in this Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) course for several years, but I had no lecturing experience beyond a guest lecture in another course. My PhD supervisor had retired the year before, and the School needed someone with the knowledge of the course and its themes to take it on. Having already exhausted my PhD stipend, I welcomed the opportunity to increase my income above what a casual tutor typically earns. I was also grateful for the opportunity to learn new academic skills, such as presenting lectures and administering courses. This opportunity presented itself as a ‘promotion’, and one in which I strongly believed I was entirely unworthy of having received. Over the years, I was presented with three more opportunities to convene courses in and outside of my School – only one of which I accepted. Between July 2016 and June 2020, I worked seven out of nine semesters as a casual convenor; the other two semesters I was a fixed-term convenor.

Being too engrossed in the excitement of my new academic identity, I was entirely unaware that I was just one of the countless casual academics who had been seduced by ‘casual convening’. This is an employment practice whereby universities hire casuals on a ‘sessional’ (i.e. per semester by the hour) basis to convene university courses. Over the years, ANU has employed casual convenors to take over the running of courses often when academics are on sabbatical or long-service leave, but also increasingly when fixed-term or full-time academics move on or retire. In my experience, casual convenors are typically a mix of PhD students and early-career researchers.

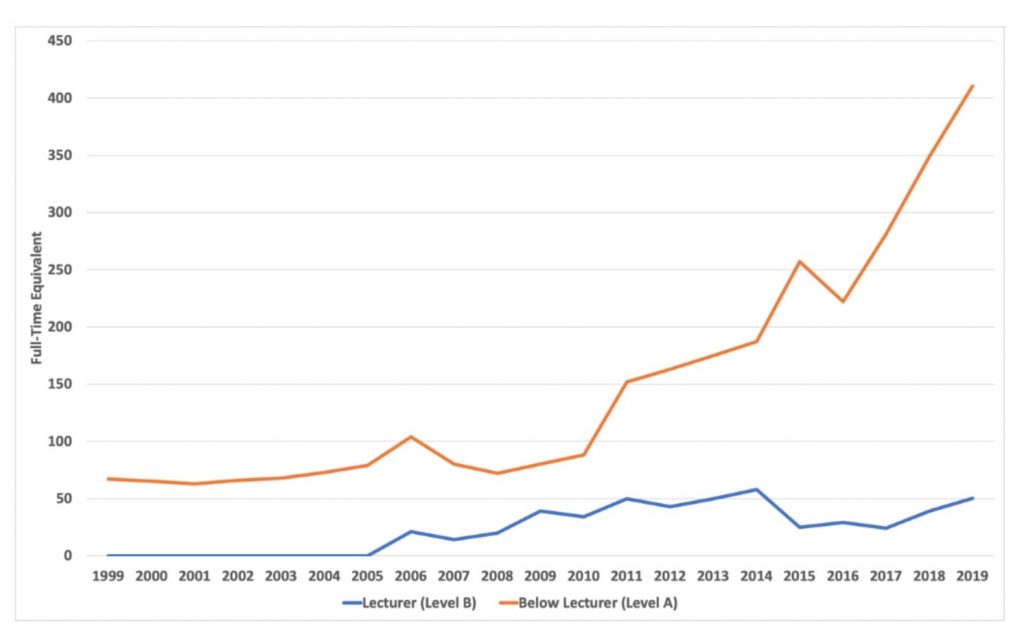

Figure 1: ANU Casual Staff Levels in Full-Time Equivalent – Level A and Level B (1999–2019)

Source: Department of Education: Selected Higher Education Statistics (Various Years)

Figure 1 illustrates the casual academic trend at ANU. In particular, it shows how ANU’s use of Level B academics (i.e. casual lecturers) has ebbed and flowed over the years, averaging around 35 full-time equivalent (FTE) each year since 2006 when I believe they first started recording this practice. Figure 1 also reveals that the past few years have witnessed an explosion in ‘Below Lecturer’ Level A academics (i.e. casual tutors). In 1999, the ANU only employed the equivalent of 67 FTE tutors, yet twenty years later they employed 410 FTE. ANU’s trend is reflective of the broader trend in Australian higher education towards casual teaching (see Figure 2).

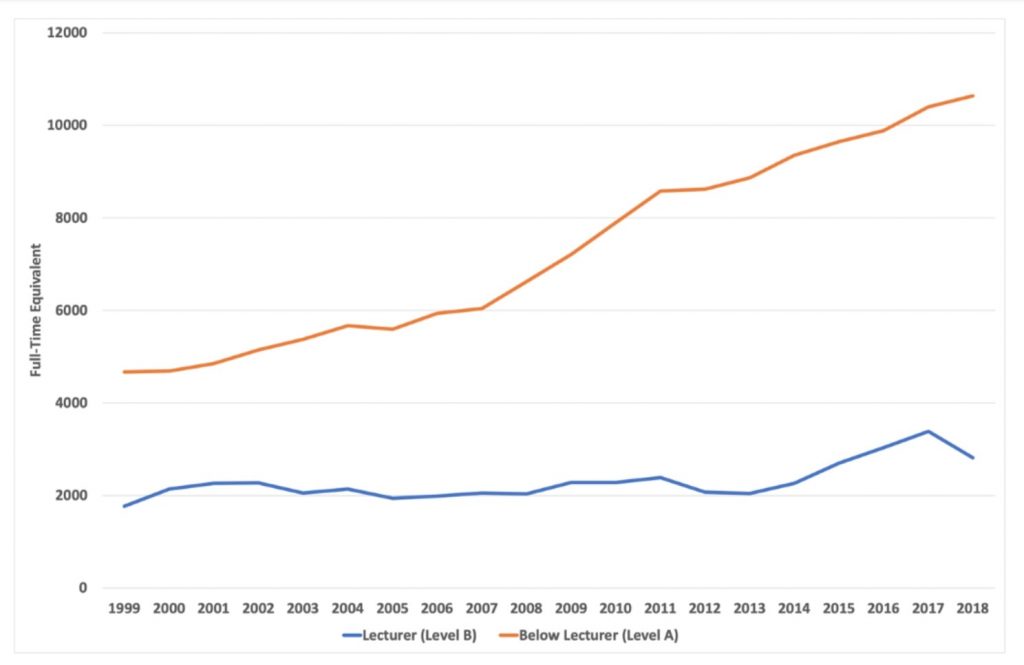

Figure 2: Australian Casual Staff Levels in Full-Time Equivalent – Level A and Level B (1999-2018)

Source: Department of Education – Selected Higher Education Statistics (Various Years)

(For those of you who are outside academia and not well-versed in its HR terminology, Level A = associate lecturer or casual tutor; Level B = lecturer; Level C = senior lecturer; Level D = associate professor; Level E = professor).

It is difficult to ascertain how many casual convenors and tutors have worked at ANU. Because of Australian government reporting requirements, universities only report the casual academic hours performed in a year, which is measured in FTE employees. (At ANU, “one FTE” equals 1725 hours). Official education data unhelpfully leaves undocumented the total number of casual academics. No universities have yet taken the initiative to publicise this data annually, seemingly because such transparency would shed unwanted light on the true nature of their employment practices. As a result, investigators find it difficult to establish accurate headcounts of casual academics, resorting to innovative methods which draw on UniSuper data and other FTE calculations.

Despite these significant limitations, I believe that knowledge of the hours that go into casual teaching can provide an indicative sense of ANU’s casual academic employment levels and its scale. At ANU, a casual tutor who takes on two tutorials of twenty students each in the College of Arts and Social Sciences (CASS) will be paid for 150 hours of Level A work (i.e. tutorial delivery and preparation, course administration and marking). Twelve such tutors will add up to just over ‘one FTE employee’ across a semester. As for casual lecturers, ANU only pays them Level B pay rates for their lecturing. For marking, tutorial teaching and course administration, they only get paid Level A pay rates. Therefore, to take on the casual convening of a course, the ANU will allocate just 96 hours for lecture delivery and preparation (based on a ‘developed lecture’ rate). Based on these hours, you would require nearly 18 casual lecturers teaching in one semester to add up to just ‘one FTE employee’.

In my early sessional years, I was oblivious to this broader sectoral and institutional trend towards casualisation, and it would take several semesters before the excitement of casual convening faded. At that point I started to realise why ANU management would provide an inexperienced lecturer with the opportunity to convene my School’s course. Yes, there was the benefit that I had tutored in the course, that I had received positive Student Experience of Learning and Teaching (SELT) evaluations and been vouched for by my PhD supervisor. Still, I believe that I was ultimately chosen because my availability was advantageous compared to continuing or fixed-term academic staff for several significant economic and financial reasons.

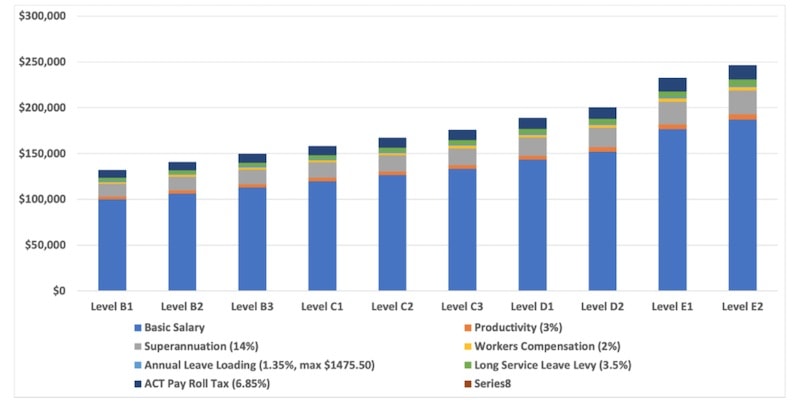

Chief among them was that the money that the university would spend on my employment was far less than it would have had to pay on a salaried academic who was the same level as my supervisor (i.e. a Level D). Figure 3 shows the yearly cost of full-time academic staff with PhD qualifications who have ongoing or 12-month plus fixed term contracts. As staff are promoted through the academic ranks, the cost of their salaried labour becomes increasingly expensive for ANU because of their basic salary, superannuation, work-cover, leave provisions, and payroll tax.

Figure 3: 2020 ANU Salary Schedule – Level B1 to Level E2 (incl. Salary Oncosts)

Source: ANU Enterprise Agreement 2017-2021 (Varied); ANU Salary Oncosts

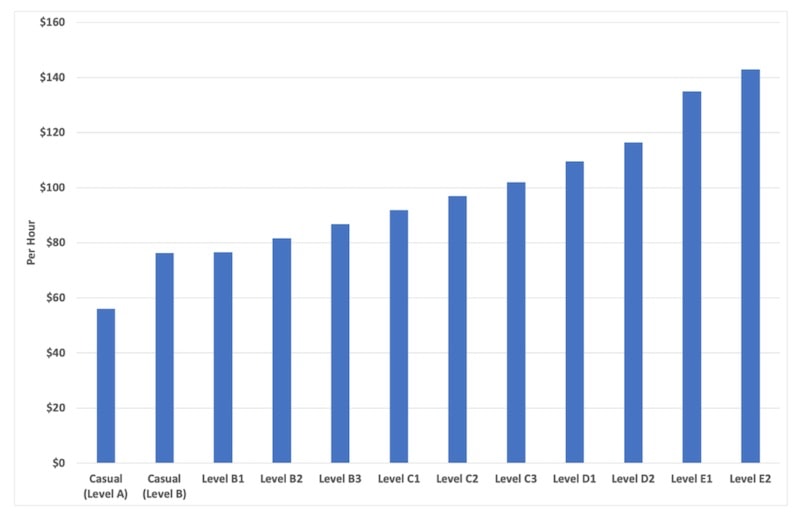

Figure 3 further illustrates how casual academics present as cost-effective teaching options for university managers. In particular, it indicates the hourly cost of salaried academics and casual academics (based on an FTE workload of 1725 hours per year). Although casual academics at ANU can earn experience and qualification loading (amounting to $6-$8 more per hour, depending on whether it is a Level A or Level B task), they cannot be promoted above their casual pay-scale, i.e. casual tutors will remain at a Level A and casual lecturers at a Level B. In contrast, salaried academics will progressively earn more per hour as they are promoted through the salary schedules. They also accrue considerably more superannuation and productivity provisions than casual lecturers (17% vs 9.5%). They are also entitled to annual, personal, long service and parental leave entitlements, thus adding to their overall cost to the university.

Figure 4: Per Hour Cost of ANU Academic Labour (2020)

Source: ANU Enterprise Agreement 2017-2021 (Varied); ANU Salary Oncosts

Another benefit to ANU was that they only paid me for teaching duties. If ANU had paid me for the whole year, then I would have had a wage similar to a Level B academic. A full-time Level B academic is expected to undertake teaching, research, non-course administration and outreach. Over the years, my tax statements showed that ANU paid me between $40,000 to $50,000 for taking on casual lecturing. If ANU had paid me as a fixed-term salaried employee in June 2016, then they would have paid me $86,646, costing them around $105,000 in salary on-costs. (I know this because I was able to secure an 11-month Level A lecturing contract in what would be the final stage of my PhD. I would return to casual academic employment after that contract concluded.) If they had employed an academic at a similar level to my retired supervisor, then it would have cost them $189,033. I was beginning to realise that this ‘casual convening’ was not what it was cracked up to be.

Research Funding, Overseas Students and Casual Academia

It was only once the pandemic hit though that I discovered there was a larger structural reason driving casual employment: over the past two decades, the Commonwealth Government has increasingly provided funding via project-based funding through the Australian Research Council, National Health and Medical Research Council and Commonwealth government departments, rather than indexed research block grants. Since the mid-1990s, funding from competitive Commonwealth grants (known as ‘Category One’) has increased within total Commonwealth research funding by 22 per cent, totalling 45 per cent or $1.6 billion in 2018. Such changes placed importance on high-salaried research academics who will secure competitive grants and produce high-quality research ‘well above world standard’. Moreover, the Australian government has also made research block grants ‘performance-based’ with past research income influencing how the government allocates the ‘Research Support Program’. (This is the research block grant that finances ‘libraries, laboratories, consumables, computing centres and the salaries of support and technical staff.’)

Reading through some blog posts by ANU’s resident higher-education expert Andrew Norton also taught me the importance of international rankings for overseas student revenue. According to this argument, increased research outputs influence research rankings which then increases the equivalent full-time study load (EFTSL) of overseas students, who base their education decisions on these rankings. The fees paid by the overseas students then fund more research outputs by buying out teaching with casuals, and the circle continues.

Moreover, it was only a couple of months ago that I also came across information in ANU’s annual reports that disclosed how the ANU’s long-standing operational grant, referred to as the ‘NIG’ (or National Institute Grant), has plateaued considerably if adjusted for inflation. Since its inception in 1946, the Australian government has provided the ANU with research funding that ‘recognise[s] the role the University plays as a national institute in facilitating key activities that are of national significance’. However, in 2018, the Australian Government provided the ANU with $199 million – just $2 million more to fund its research activities than it provided in 2004. The proportion of ANU’s NIG in overall university revenue had fallen from 31 to 13 per cent in the fifteen years leading up to 2019. The conversations that I had with my senior colleagues about the importance of Australian Research Council grants and other competitive grant income were starting to make more sense. Because ANU could no longer rely on its NIG to index yearly, these competitive grants provided the University with crucial income for research.

I began to appreciate that my type of employment and overseas student income was alleviating these structural funding issues for University management and researchers. While I was trying to wrangle my head around China’s environmental policy reforms in my PhD, I was oblivious to the significant increase in overseas undergraduate and postgraduate income pouring into Australia and the ANU. I knew I was teaching more overseas students. However, I did not register the magnitude of the increase and how the total fees that overseas students paid for their ANU education exploded from $116 to $328 million in the five years leading up to 2019, reflecting a broader trend in Australian higher education.

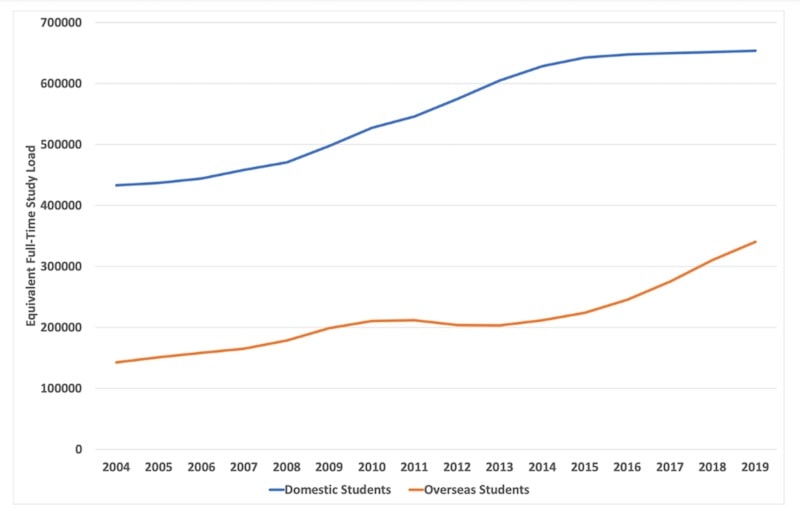

Figure 5: ANU’s Actual Student Load – Domestic and Overseas Students (Bachelor and Masters Coursework): 2004 to 2019

Source: Department of Education: Selected Higher Education Statistics (Various Years)

What all this means though is that, in an increasingly fraught competitive research funding environment, ANU has increasingly been forced to rely on overseas student income to fund its ‘core mission of research’. Moreover, the Gillard Government provided an additional source of income when it moved to a higher education demand-driven system that uncapped Commonwealth supported places (CSP) for domestic students. This funding change in 2012 and CSP quota increases in the preceding four years led to more Australian students studying at ANU (see Figure 5). These students and the Australian taxpayer provided more opportunities for eager researchers to ‘buy out’ their teaching with casual academics. University managers believed that, if the funds were there, it made little sense for researchers to take on the laborious task of teaching when the viability of the university in their eyes increasingly depended on research and (successful) grant applications – both time-intensive undertakings. It also seemed sensible to fill ad hoc and short-term teaching vacancies with casuals. Why foist significant teaching work onto salaried academics, which could impact their research output, when you could transfer that work to an inexpensive employee? The result of all this is that casual convening became established and ANU’s use of casual tutors grew by seven-fold in the space of two decades. Moreover, ANU’s academics were afforded enviably light teaching loads.

The pandemic has revealed the unsustainable nature of this business model. But for a time, it seemed like ANU had found a golden goose as shown by its research output, impact and outcomes; its international rankings; and its increasing number of overseas students prior to 2020 (see Figure 5).

Casual Academics, Course Fees, and Surplus Income

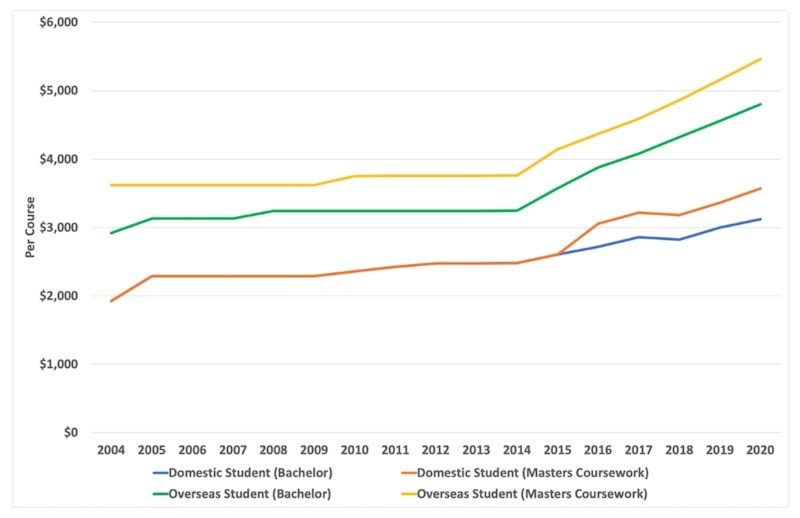

I also found out that the rationality behind the use of casual academics seems logical when you delve into the course fees paid by students. Figure 6 details the trend in fees that domestic and international students have paid for an ANU education in the Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) over the past decade and a half. Whether these two sets of student cohorts are lectured or tutored by a professor who has 30 years’ experience and won numerous (or no) teaching awards, or a PhD student who has several years or no prior teaching experience, has no direct bearing on the amount that they pay for their education. It only varies according to the level of the course (e.g. undergraduate or postgraduate) and the resident status of the student (i.e. domestic and international student). Therefore, course income per student remains standardised regardless of the convenors’ quality of teaching or experience. (Course revenue would only be affected if students dropped the course because of the quality of its teaching, which does happen).

Figure 6: Domestic and Overseas Student Fees for ANU’s Humanities and Social Science Courses (2004–2020)

Source: ANU’s Program and Courses

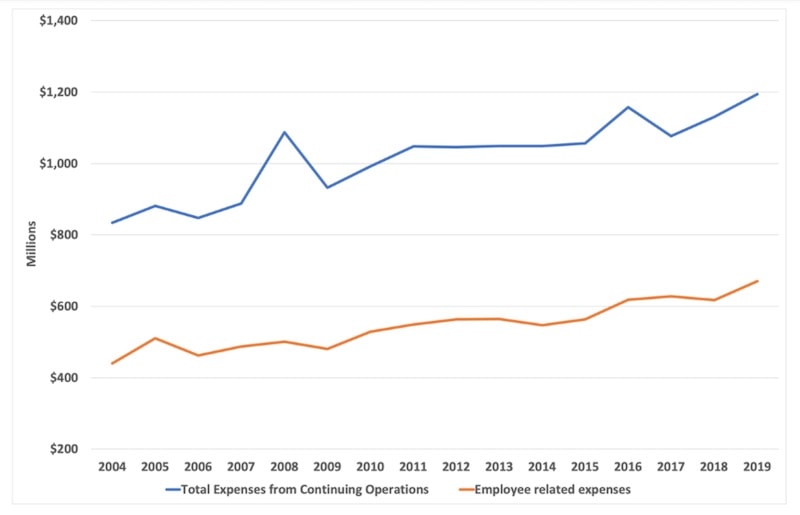

Because I was paid for just my teaching, I generated substantial profits for the University, the College and the School; something very welcome to them when viewed in the context of my earlier discussion surrounding research funding. Before I go into this surplus income, it is necessary to note that Australian universities have become increasingly expensive institutions to run, with overall combined expenditure reaching nearly $33 billion in 2018. ANU is no different. Funding employee-related expenses, universities services and equipment, building construction, investments among other expenses have all become increasingly costly. In 2019, ANU’s overall expenditure was over $350 million more than it was a decade and a half earlier (see Figure 7). Its employee-related expenses had also grown by $230 million over the same period. (These figures have been adjusted for inflation). ANU has also amassed significant assets totaling over $4 billion at the end of 2019.

Figure 7: ANU’s Total Annual Expenses from Continuing Operations and Employee-Related Expenses (2004–2019)

Source: Department of Education, Skills and Employment’s Finance Publications (Various Years); ANU: NTEU Information Request

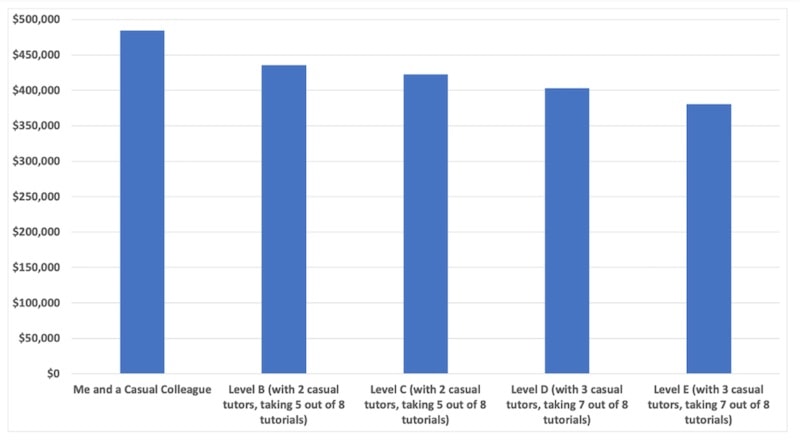

With that point squared away, let us get back to the question of course profits. Figure 8 clearly illustrates how casual convenors have generated significant levels of profit compared to their salaried colleagues (i.e. course profits = course fees – direct cost of teaching). While the amounts may vary, these surpluses occur regardless of course size because of the disparity in remuneration noted earlier.

Figure 8: Profit per Course – ANU HASS Course of 160 Students (Casual to Level E)

Source: Programs and Courses (Fees); Academic Staff Salary Schedule; Academic Casual Sessional Rates

For example, in 2019, when I convened my School’s course, I had my largest course enrolments with 160 students (148 undergraduates and 12 postgraduates) – up by 50 per cent from the year before. Based on its mix of domestic and international students, this course drew in around $522,000 in fees. Therefore, once the casual wages and oncosts of my casual tutor and me were deducted from the course revenue income, ANU was left with a considerable profit: just under $490,000 to cross-subsidise other parts of the School, College and University. Marx would call that some serious alienation from the fruits of labour. If that course had been taught by a Level B with two casual tutors taking five (out of eight) tutorials, then that surplus would have fallen to around $435,000. It would have fallen by more than $55,000 if it was taught by a Level E with a typical senior academic tutoring load (see Figure 8). My end-of-semester Student Experience of Learning and Teaching (SELT) evaluation scores averaged around 4.4 out 5, so why hire a salaried academic when you can have the casual sort who has already achieved reliable pedagogical and financial results?

Casual Wage Theft in the Academe

While these musings reveal the governmental, sectoral and institutional forces that have driven casual academic employment such as mine, they do not indicate the relatively opaque (and arguably immoral) financial logic that drives the proliferation of casual academics. That only becomes apparent once you realise that university enterprise agreements have miscalculated the time devoted to academic duties, thus making it even cheaper to hire casual academics. After a couple of years of teaching my courses, I realised that the hours that I put into the course were most certainly not reflected on my paysheet. I was investing full-time hours in the course through lecture preparation, course administration and marking, often forced to work on weekends and shelve all thesis writing, but I had the yearly pay that positioned me well below ANU’s lowest-paid professional staff and sometimes just a notch above the minimum wage. This was despite, as mentioned above, teaching a course that brought in several hundred thousand dollars in course revenue.

It only took some recent preliminary research into academic casualisation before I discovered that casual academic work was priced incorrectly because of a four-decade-old Academic Salaries Tribunal (AST) decision. That AST decision stipulated the hours required to perform various academic tasks. For some reason, universities have stuck with this decision, despite, as I will show below, strong evidence pointing to its unsound basis.

After I spoke up at an ANU Staff Forum about the plight of casuals, I attempted to calculate the time that went into academic teaching in order to calculate the ‘structural wage theft’ that I had experienced. It was quite easy to throw out buzzwords like ‘wage theft’ in front of the Vice-Chancellor, but it was somewhat more difficult to quantify this theft. However, before I start that quantification, it is important to define ‘structural wage theft’. This wage theft is not the sort that newspapers and the nightly news have reported in recent years. That type occurs when a celebrity chef or a national supermarket chain underpays their workers often by paying them less than the award wage. If you define wage theft in this manner, then you can confidently proclaim, like ANU’s Vice-Chancellor, that your university does not engage in this practice. Such wage theft has occurred at ANU, and at significant levels, but it is definitely not a widespread practice even if it would still occur in isolated instances. The type of theft that primarily occurs within ANU and other universities results from a correct reading of its enterprise agreements. That is why I define it as ‘structural wage theft’. This theft is embedded and normalised within these documents because university pay rates attribute incorrect levels of workload to academic tasks. In other words, casuals regularly cannot finish their work to a standard befitting an academic institution within the hours set by management.

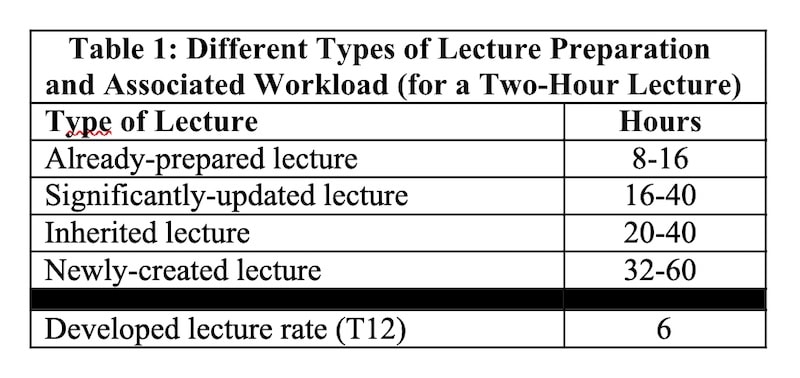

Take lecturing, for example. ANU’s Enterprise Agreement stipulates that casual academics can prepare a two-hour lecture in six hours. However, my experience quickly revealed to me that six hours was an unsatisfactory hourly allocation due to the varying levels of work involved with different types of lecture preparation (see Table 1). Conversations with several casual colleagues afford me the confidence to say that I am not alone in this view. When I first started teaching in my School’s course, the former course convenor provided me with ‘inherited lectures’ from a course that they had led for close to twenty years. These inherited lectures allowed me to prepare a lesson based on their PowerPoints. However, even these inherited lectures require significant work. They take around 25 or more hours of preparation because of the need to listen to past recordings, undertake further reading, prepare talking notes, master a narrative and refashion the PowerPoints to reflect your voice/style.

Over the years, as I continued to teach in the same course, I progressively moved to the ‘already-prepared lecture’. These involved far less work ranging between 8 to 16 hours of preparatory work (see Table 1). The range reflects the type of work that goes into updating and delivering a university lecture in HASS. These lectures can still involve significant work due to the need for updated reading, PowerPoint revisions and the need to reacquaint oneself with the lecture material (i.e. present it effectively and engagingly for two hours after not substantively encountering the content for 12 months).

I also wrote new lectures and significantly updated another few lectures. Although qualitative SELT evaluations demonstrated that this additional content enriched the course, it was, in hindsight, quite foolish, if I had wanted to avoid wage theft. ‘Newly-created lectures’ take quite a bit of time to create, roughly between 32 to 60 hours (see Table 1). The substantial time involved with these lectures comes from levels of reading involved in creating these lectures. If an academic wants to avoid lectures that regurgitate the narratives provided in textbooks in a paint-by-numbers style of teaching, then they have to read and synthesise large bodies of literature and information into an engaging story that fits with the broader themes of the course. (Sometimes, it takes a couple of years to hone that narrative!). Lectures that involve significant updating also involve quite a bit of work ranging from two to five eight-hour days, depending on the levels of reading needed to update the material.

I also soon discovered that the time needed to administer a course of between 100 and 150 students was quite significant. The university did provide me with 35 hours of course administration, but that was quickly consumed before Week 1 by answering student emails, liaising with administrators, creating online course sites, writing course outlines and devising new assessment, among other pre-semester tasks. Then from the start to the end of the semester, I was forced to devote at least 98 hours of work per semester (16 weeks incl. teaching break and exam period) to course administration. It varied from week to week, increasing early on in the semester and around assessment deadlines when students were most in need of email advice or face-to-face student consultations. Over the semester, it would average around six hours a week. I could have cut this time involved in course administration, by ghosting student emails or rejecting requests for in-face consultations because of my employment status. Such actions, though, would have jarred with my teaching ethos. (It also would have resulted in justifiably lower student satisfaction with the course).

Surprisingly, I did find that the hours allocated to tutoring work, as a casual convenor, were more than enough if I avoided preparing a new tutorial. According to ANU’s EA associated workloads, non-repeat tutorials allocate two hours preparation and administration and repeat tutorials allocate one-hour preparation and administration. Casual convenors who take on four or more tutorials will typically avoid unpaid overtime when preparing tutorials in the same course. They come out roughly even, or they do not have to complete some hours of work across the semester. For new convenors, more work needs to go into tutorial preparation. The reason for the lack of wage theft from this type of work is that student administration is placed under course convening responsibilities. Additionally, tutorial preparation for convenors does not involve watching their lectures! However, non-convening casual tutors do experience wage theft in other ways as I discuss later on in this article.

Marking was one area where I was able to avoid wage theft as I progressively became more experienced. ANU compensates marking duties on a rigid per student per semester basis – 90 minutes per student per semester in casual HASS contracts. In the early stage of my teaching career, I would put in more hours than allocated to ensure students comprehensively understood where they could improve (well in excess of the 90 minutes per student per semester). However, I soon learnt to mark to the hours that I was assigned. Unless it was a problematic essay, then I did not often exceed the 50mins allocated for a 2500-word paper. I found marking shorter pieces more challenging to keep to the allotted minutes (15 mins for 750 words), but then I would make up for that by having a final assessment that was marked under exam conditions, i.e. no comments. I strongly doubt that this would have been the case, though, if I had worked at other universities, such as University of Canberra, that I understand allocate just one hour per student per semester, regardless of the assessment structure.

For those who read through the last six paragraphs, these passages could perhaps come across as dry, at first blush, but it is necessary to carefully explain the substantial work that goes into all aspects of lecturing, convening and tutoring. The figures are not accurate to the minute nor the hour, but they do help reveal the scale of casual academic wage theft that occurs at not just ANU but universities around Australia. To show this, I will provide another personal example from several months ago and compare it with the more realistic non-Academic Salaries Tribunal workloads discussed above.

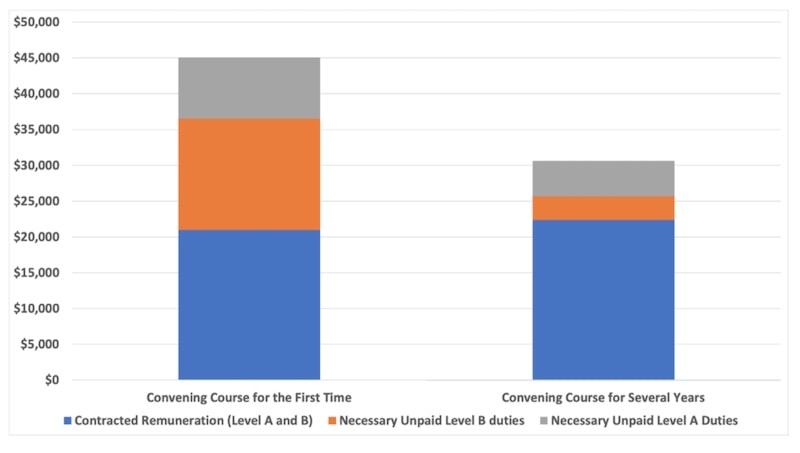

In July 2020, before I was offered a new 11-month fixed-term contract, I was scheduled to receive a casual academic contract to lecture and tutor in the same course that I first took in June 2016. The course was correctly estimated to have around 140 students despite the pandemic, of which I convene, lecture and conduct four tutorials totalling 85 students. For this, the university would have allocated 96 hours of Level B work (lecturing) and 268 hours of Level A work (tutoring, marking and course administration) that would have totalled around $20,595. However, as shown by Figure 9, that casual contract would have undervalued my teaching by $24,233 if I had taught that course for the first time. To adequately convene that course, I would have toiled for over twice as many hours as management had allocated in my contract: 228 hours of unpaid lecture preparation and 145 hours of Level A duties. In the case of a repeat course, the wage theft would have been calculated at around $8,348 with 84 hours of unpaid Level A duties and 48 hours of unpaid Level B duties. (The $1400 difference in remuneration in Figure 9 is due to experience loading). Once again, these wage theft amounts are indicative; they are based on workload averages. However, it matters little if wage theft totals $2,000 or $30,000 a semester. A practice that exploits vulnerable employees in this manner, regardless of its scale, must be stopped.

Figure 9: Calculating ‘Structural Academic Wage Theft’

Source: Academic Casual Sessional Rates

Reflecting on Casual Teaching and Academic Solidarity

When Green Agenda commissioned me to write this article, I initially decided to write it in a formal tone. The aim was to convey the ills of casual academia and my thoughts for reform neutrally and in as few words as possible – I have failed in that aim! However, the mere process of writing this piece made me soon realise that a formal tone would have to yield to a reflective voice if I was to describe the systemic issues that plague higher education in a manner that befits the seriousness of the situation. I could not remove my subjective experience from the analysis.

I have also had to keep the scope focused on my experience and the economic incentives that have facilitated casual academia. However, it would be unwise to sidestep a quick discussion of the general state of casual teaching. Conversations with fellow casuals around (virtual) water coolers suggest that the tensions between teaching, research, inadequate compensation, and aspirations for scarce ongoing positions can disincentivise pedagogical integrity. This is already true among many permanent academics, who are arguably over-incentivised to cut corners on teaching given the comparative weight placed on research with regard to career advancement and job security.

For casual academics, these tensions can prove even harder to negotiate. On the one hand, teaching contracts pay the rent and stock the fridge with food. The circumstances of adjuncts/casuals in the US portends to how grim this tenuous existence can become. However, teaching alone is unlikely to land casuals an ongoing role (or even simply a more secure fixed-term position). This is true regardless of how exceptionally talented a teacher may be; their success in attracting students; the innovative methods they employ; and their contributions in developing curricula and building entire programs.

Moreover, the perpetual vulnerability can arguably compromise academic freedom. For example, SELT evaluations can place casual staff in highly compromised positions. Poor evaluations may mean such persons are not given further opportunities, which effectively ends many academic careers. Strong evaluations are also required for job applications. The result is that many sessional staff work far in excess of their allocated hours, given their entire vocation may rest on the opinions of perhaps only a handful of students who bother to click on the SELT survey link.

The point of this reflection has also not been to single out specific individuals as facilitators of this employment practice. Keen readers will have already noticed that I have been vague surrounding the details of my courses and School. It has not been done in an act of career self-preservation – my head is already well and truly above the academic parapet! But I believe it would do a disservice to the casual cause to particularise these details to a department when the issues that befall our higher education sector are structural.

However, I would be disingenuous if I did not concede that I have been disappointed with the response of some salaried colleagues who have shunned applying the same fervour to combating academic casualisation as they do for other inequities. Furthermore, my experience of NTEU ANU Branch Meetings over the past year has demonstrated to me that too many academics are firmly wedded to pay concerns, rather than work conditions. Casual campaigns such as the ACT University Casual Network’s open letter to Brian Schmidt also garnered some, but less salaried solidarity than I expected.

Yet I equally recognise that their present ‘indifference’ can be traced back to the 1980s ‘Dawkins revolution’. Since then, academic departments have witnessed a slow atomisation, as the modern ‘enterprise university’ has replaced the university of yesteryear. Solidarity has given way to self-preservation as even permanent staff are increasingly feeling precarious in the face of increasing research demands. The modus operandi now is to keep your head down lest you draw unwelcome attention to yourself.

The Future of Casual Academia: after the pandemic

Where to from here? How should universities operate after the pandemic? My article has not only allowed me to reflect on the problems that plagued academia before the pandemic, but also consider the future that I believe will deliver a more just university workplace. The ideas that I will put forth are not radical, they are equitable and sensible, and they have resulted from serious thought and rumination.

Firstly, it should come as little surprise that I am vehemently against casual convening. Universities should abolish this indefensible employment practice. Although the degrees of wage theft may vary, personal and anecdotal evidence in and outside ANU strongly suggests that the vast majority of casual convenors will experience substantial wage theft. ANU and other universities should only continue to employ casual convenors if they can prove that these contracts fairly remunerate their employees.

Early signs indicate that a handful of VCs recognise casual academic employment creates problems. Comments by ANU Vice-Chancellor Brian Schmidt at several staff forums suggest that he believes casual teaching at ANU is neither beneficial for the employee nor for ANU. The VC has recently established a joint ANU-NTEU Secure Employment Working Group (SEWG) intending to implement a pilot program in Semester One, 2021, that he says will inform the reform of ANU’s 2021 Enterprise Agreement. (I have been appointed to the SEWG.)

I am looking forward to hearing the views of others in the working group. However, before I start that collaboration, I will canvas what I believe are other critical employee relation reforms for ANU (and the broader sector). The first of these is the select introduction of teaching-intensive positions, otherwise known as Teaching Fellows. Conversations with some colleagues around ANU’s (online) corridors has highlighted to me that these positions have a terrible name. It is little wonder when you hear how institutions, such as the University of Sydney, have used these roles. They have reduced these employees to ‘teaching mules’ with crushing workloads spread across multiple courses with deep-seated consequences for departmental collegiality and staff morale. These positions are rightfully seen as an exploitative path to tenure.

However, to think that teaching-intensive positions have to be like that is short-sighted. In particular, they can be used in popular courses where a crucial factor in student retention for School programs is the quality of the lecturer. In the enormously important 1000-level courses that form the bedrock of undergraduate study, there is a compelling argument to be made for assigning dedicated Teaching Fellows, allowing them to refine both their teaching craft and course content in ways designed to be maximally engaging and effective. Too often, these critical courses are assigned to casual staff – who almost invariably give their best but are faced with the difficult task in managing such large courses on a one-off basis. Or they are convened by permanent faculty members who are already stretched with research commitments, resulting in course content that is stale, delivered poorly, cuts corners in assessment, or otherwise falls well short of its potential for enlivening the intellectual spirits of our undergraduate students. If Teaching Fellows are given responsibility for managing large courses dedicated to core disciplinary content, then other continuing academics can take on later-year courses – especially specialist electives – that prove more complementary to their research interests. However, universities must ensure that Teaching Fellow workloads are appropriate and allow them to continue to research even if it does comprise a less crucial part of their academic KPIs. We must avoid reducing such employees to little better than college teachers. Further, management should base the selection criteria for these positions on a pedagogical basis. These jobs should not be seen as a steppingstone to other research-intensive parts of the university. Management should also base promotions on teaching performance indicators. We need to reject the attitude that continually positions research above teaching.

Although my story has primarily centred on the experience of casual convenors, the associated workloads linked to academic tutoring also require urgent reform in new university enterprise agreements. I am not against casual tutoring per se. However, to adequately prepare for a non-repeat tutorial commands more than two hours work. It involves at least five hours work to watch lectures (2 hours), read tutorial material (2 hours), prepare tutorial plans (30 mins), and tend to course administration (30 mins). I have admittedly revised these workloads upwards in a conservative manner, but they would still deliver fairer remuneration than past pay-scales. Budget-wise increasing the associated workload to five hours for a non-repeat tutorial would make each tutor to the tune of $1300 richer per course in ANU’s HASS subjects based on my calculations. That is chump change when you consider that one international student pays $4800 per course for their ANU HASS education in 2020. If universities are not prepared to pay this adequate amount, then they should openly state this in marketing brochures in order to fully disclose to prospective students the workplace conditions of their teachers. Alternatively, university workplace human relations guidelines should stipulate that tutors should under no circumstances work beyond their allotted hours – even if it means they are woefully underprepared for tutorials or they are forced to ignore student emails.

The result of these new reform measures is that universities will find it increasingly challenging to fund casual employment at the levels it has in the past. If you stop employment practices that have stolen tens of millions of dollars from casual employee wallets, then there will be employees and departments across the university that will lose their valuable source of cross-subsidisation. Moreover, the result of appropriately priced academic labour is that casuals will find it challenging to secure academic work. This is the price of a much-needed market correction. Many of those ANU casuals who comprised the 410 FTE in 2019 would not have secured their employment if it was not for the low value university management has attached to their worth. However, going forward we still need to give PhD scholars at ANU and around Australia the opportunity to teach. It is an important element in their academic training. Perhaps that could be done formally as part of the PhD experience, as some have suggested. Universities should also increase PhD stipends so PhD students are not forced to rely on large casual teaching loads to survive, which often results in ‘time-theft’ from their research.

Nevertheless, until university budgets grow to a level that allows the correct funding of casuals, it will mean that salaried academics will have to take on more teaching. Overall that presents as a positive development. Conversations with countless students over the years gives me the confidence to declare that they desire to have their lecturer tutor them. Moreover, discussions with senior ANU academics have stressed to me that levels of teaching undertaken by academics within the Faculties (pre-2008) was far higher than the levels at ANU just before the pandemic. Back then, it was not uncommon for academics to take on four or more tutorials as part of their ‘academic darg’.

At ANU, at least, there is the belief that because of the National Institute Grant, its academics are entitled to their pre-pandemic levels of teaching. ANU avoids reporting academic workloads, but anecdotal evidence suggests many of its academics have teaching workloads that comprise of no more than two-hour lectures and one tutorial group each week across a semester. In many cases, ANU’s academics have avoided the 40:40:20 split, whereby yearly academic workloads are split between research (40 per cent), teaching (40 per cent), and other tasks (20 per cent). My calculations place their split at 15 per cent (teaching), 65 per cent (research) and 20 per cent (other). (These percentages are based off the hours that the ANU Enterprise Agreement stipulates for casual academics, so I admit that my calculations may be somewhat cheeky!). ANU management seems to have used overseas student fees and casual labour to buy out teaching as a form of employee pacification for reluctant teachers. I sincerely hope that my analysis earlier surrounding wage theft has disabused many salaried academics of this entitlement. Yes, the NIG in part funds their research, but surplus course profits and wage theft has been extremely critical in funding their low levels of teaching.

My hope is that over the next few years, university employee relations move from pay rise concerns to serious discussions surrounding workloads and conditions. It would be refreshing if the NTEU reprioritised its log of claims in favour of workplace conditions and workloads that improved casual conditions at ANU’s next enterprise bargaining round. Beyond my other recommendations, why don’t we start with all university employees deserving the same superannuation? Unless management can provide a sensible explanation for the stark discrepancy, ANU must raise casual superannuation to 17 per cent in its new enterprise agreement.

In addition, we need to have a genuine conversation about whether senior academic salaries are appropriate in the ‘new normal’ that universities have found themselves. Perhaps we could have avoided these conversations, but academic wage theft and a tight funding landscape has necessitated a discussion on the appropriateness of certain salary expenses. In particular, is it appropriate that Level E academics earn $187,000 at ANU? Have we valued this level of academic work correctly in a higher-education system that regulates fees? I ask these questions genuinely. Because as it stands, Level E academics earn well above what an Executive Level 2 Commonwealth public servant who earns typically around $140,000 at the top of their levels. And, in contrast to their public service counterparts, non-Head of School professors are not required to manage anything more than a group of tutors. I have calculated that based on ANU’s staff profile in 2020, reducing the Level B to E salary schedule range from ‘$99,809–$187,079’ to ‘$99,809–$152,171’ would yield savings of around $25 million (or the equivalent of 193 Level B positions). Perhaps senior academics could grandfather their relatively high salaries for better workload conditions in the future.

For the same financial reasons as discussed above, we also need to have serious discussions about other expenses on the left-side of universities’ financial ledgers: salary and non-salary related. As an institution, ANU is an administratively heavy compared to other universities. This article does not take an elitist view on non-academics. They can help ensure ANU delivers on its core missions. However, as a fundamental principle, management should look for financial savings in non-core parts of the university before they extract savings from teaching staff.

With regard to ANU management, we need to keep questioning the appropriateness of their salaries. However, I am going to avoid repeating the typical refrain that highly-paid staff (i.e. over $220,000) are the reason for ANU’s financial instability. Recent disclosures show that ANU in 2019 spent nearly $20 million less on ‘other highly paid staff’ than it did in 2013. It employed 112 fewer employees as well. (The average wage did increase though by over $48,000 per employee). Nevertheless, ANU’s Workplace Gender Equality Agency submissions afford me the confidence to state that management personnel at ANU grew from 391 to 484 employees in the five years leading up to June 2019. We need to have serious conversations as to whether such high numbers of management are appropriate for a ‘smaller university’ that has hitherto provided inadequate remuneration for large sections of its teaching staff? My view is that they are not.

We also need to think genuinely about whether the glittering buildings that adorn university campuses such as ANU are suitable if the basic inequities that I outline still exist. Until that happens construction should cease, and every building constructed at ANU in the modern era should have a sole brick that states “This Building Was Partly Funded by The Unpaid Labour of Innumerable Casual Academics”.

Lastly, I provide a recommendation for my casual colleagues. (Yes, I still identify as a casual). I recommend that they withdraw themselves from the academic market that has under-priced their labour for too long. They need to demobilise from the ‘reserve army of academic labour’. I base this suggestion on ‘my road to Damascus’ moment, and the realisation in July 2020 that I could no longer work casually. I would not work strictly to the hours I was allocated, thus diminishing my students’ learning experience. I also could no longer work all the hours needed to adequately prepare and administer my course, thus ensuring my complicity in wage theft. Both options were unpalatable. Therefore, I decided that I would only work as a full-time academic employee, even if it meant potentially not teaching again. I admit that my outcome was highly fortunate in the short-term. Nine times out of ten, such a decision would have resulted in a ‘thank you for your service’ from management and a subsequent visit to Centrelink. Moreover, in the long-term, I am not guaranteed any more work beyond June 2021. However, the point here is not to evaluate my decision in a self-serving sense. Instead, casuals need to start operating based on solidarity with other casuals. If casuals continually accept these unfair contracts, then management will continue to offer them. It will only be when the supply of academic labour becomes scarce that real change will occur in remuneration and employment conditions. Casual academics need to think collectively, even if such thinking will result, for many of them, in non-academic futures.

To finish, I sincerely hope that casual academia in Australia has reached a pivotal moment. When higher education historians discuss the state of universities, they will point to COVID-19 as the catalyst that drew attention to an immoral employment practice and forced universities to reflect on the sectoral, governmental and institutional dynamics that facilitated incalculable theft from their casual teachers….because, like with any injustice, it doesn’t have to be this way.

2 thoughts on “A casual reflection on academia: before and after the pandemic”