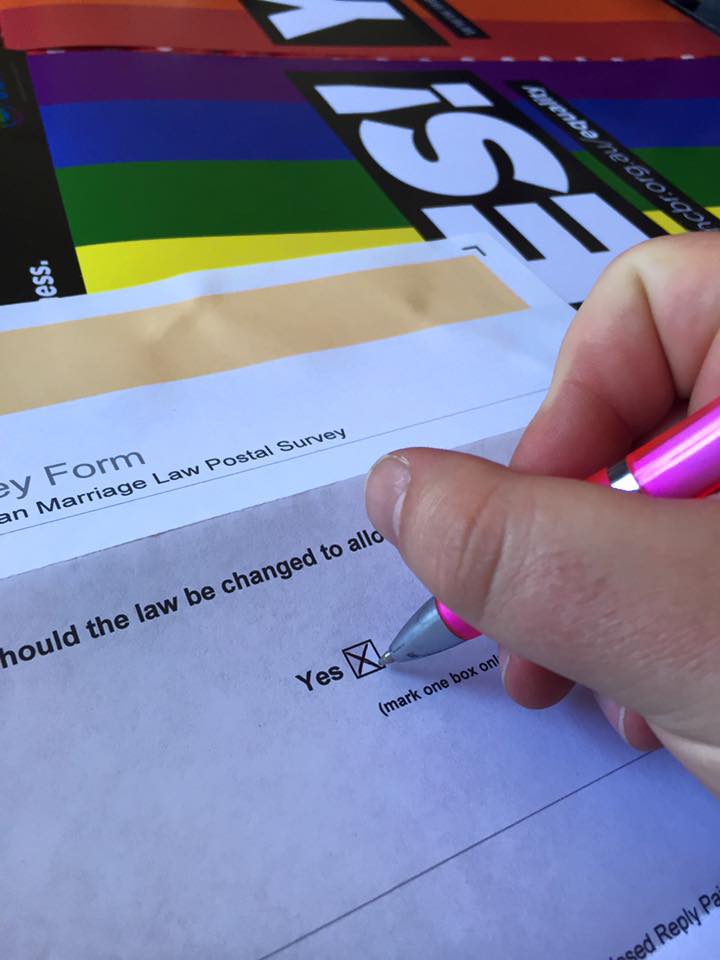

The postal survey on marriage equality in Australia has opened deep questions about the intersection between human rights and democracy. In this discussion community campaigner Hayley Conway and researcher Mary Tomsic debate what role citizens should play in voting for the rights of others.

Hayley Conway: We already vote on the rights of others

Citizens already do vote on the rights of others – by electing representatives who participate in the parliament and subsequently vote on a range of legislation that impacts on other citizens. The crucial difference between general elections and plebiscites or referenda, however, is that in general elections citizens select representatives based on a platform of issues that enable them to decide what is most important and vote accordingly. In between elections, citizens can engage with these representatives, campaign and lobby for change, and even be open to changing their own minds on an issue over time. Plebiscites do not allow for this, and instead bind both electors and their representatives to a position that is little more than a snapshot of public opinion.

Citizens already do vote on the rights of others – by electing representatives who participate in the parliament and subsequently vote on a range of legislation that impacts on other citizens.

Research bears out these concerns. In 1998, Professor Sherman Clark wrote in Harvard Law Review that plebiscites erode our ability to advocate for and engage with systemic change, in favour of answering a binary question on a single issue. More recently, a 2015 study of 120,000 voters across 48 US states, conducted by researchers at the London School of Economics US Centre, concluded that “ballot initiatives have no positive effect on political knowledge”. Finally, analysis of ballot initiatives in Switzerland (the country that uses this mechanism more than any other) found that the direct and indirect effects on religious minorities are consistently negative and can even lead to harsher laws being proposed in parliament because politicians fear a reactionary popular vote.

I’m not arguing that our representative democracy is perfect, it is far from that. Nor am I saying that there are only democratic questions to resolve, there are also broader philosophical questions about who wields power in our democracy and social institutions and if they should be able to vote directly on the rights of others – I’m hoping we’ll address those questions later in this piece. Broadly speaking, however, plebiscites, referenda and direct democracy are poor tools for determining the rights of fellow citizens – especially if the rights being questioned are those of a minority.

Mary Tomsic: Public votes have their role to play in public debates

As Hayley says, Australian citizens are already endowed with the responsibility of voting on the rights of others. Hayley highlights the importance of considering the differences between voting for representation in parliaments and the specific instances when citizens are called to vote in referenda, plebiscites or in this current case, a voluntary non-binding postal survey. The argument is made that voting on specific issues, in referenda and plebiscites, limits systematic change and ‘is little more than a snapshot of public opinion’. The debates and impact around these occasions can be revealing and understanding these moments when public opinions are voiced allow us to see what issues mean to people at various moments and how people’s rights and responsibilities are understood.

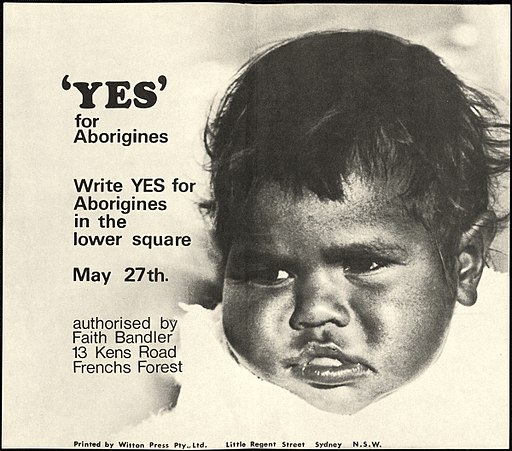

I don’t want to argue that referenda and plebiscites are necessarily the best (or even a good) method to lead change, but they are tools that government use. It is the public debates around referenda and plebiscites that reveal the ways in citizens understand particular issues, and voice their opinions accordingly. Referendums are sometimes required to make changes to the constitution, such as in the case of the 1967 referendum to recognise Indigenous people in the Australian constitution, the referendum which has received the highest Yes vote (90.77%). This form of recognition of Indigenous Australians was achieved through considerable Indigenous activism alongside bipartisan political support.

It is the public debates around referenda and plebiscites that reveal the ways in citizens understand particular issues, and voice their opinions accordingly.

The plebiscites held on military service in 1916 and 1917 (often remembered as referendums on conscription) were initiated by Prime Minister Hughes who wanted to extend existing compulsory military to overseas locations, to supply more troops for the war. Hughes couldn’t gain parliamentary support for this plan, but felt if he had a public commitment for conscription he would be able to pressure politicians to make this legislative change. Both plebiscites narrowly failed and Australian citizens have not been asked to vote directly on this issue since.

Historian Joan Beaumont has described the nature of the public debate around these campaigns as one ‘that has never been rivalled in Australian political history for its bitterness, divisiveness, and violence … What was at stake it soon emerged was not simply a disagreement about military need for conscription, but an irreconcilable conflict of views about core values: the nature of citizenship and national security; equality of sacrifice in times of national crisis; and the legitimate exercise of power within Australia’s democracy’ (quoted on the National Museum of Australia website, campaign materials for both sides are available on the Australian War Memorial website and the State Library of Victoria). These fierce public debates around conscription reveal the competing ideas and understandings about the desired roles for Australian citizens that remain unresolved.

I don’t want to make any simple comparisons between past and present cases – other than to point to the importance of critically examining the nature of the debates. I don’t think the Marriage Equality survey is the way our government should deal with this issue, but, what the current campaign reveals to us, is what’s at stake for some of those publicly involved in the debate, including how gender and sexuality is understood; the value of the institution of marriage to people; and most significantly, which particular issues of rights are given prominence in the public sphere.

Hayley Conway: Public votes are not beneficial for determining how minorities can exercise their rights

We agree that referenda are not the best way for dealing with people’s rights. I’ll now show that referenda, in its various forms, are not beneficial methods for determining if or how minorities can enjoy or exercise their rights.

A vote affirming the rights of a minority doesn’t lead to systemic change. The 1967 referendum recorded an overwhelming yes vote. This vote allowed the federal government to legislate for Aboriginal peoples (a responsibility that under the Constitution lay with the states) and advocates believed that this would mean improvements in the treatment of Indigenous people. The intention and goodwill that carried that vote has had next to no impact on the rights enjoyed by Indigenous Australians. The forcible removal of children, resulting in the Stolen Generations, didn’t end until the 1970s, the Intervention in the Northern Territory commenced with the federal government suspending the Racial Discrimination Act, and the logic that justifies settler mentality (also known as racism) is still prevalent in both the Australian populace and government policy.

Systemic change is needed to end discrimination. Winning the ‘yes’ vote in the postal survey will not end homophobia and the campaign itself has given great licence for public homophobia, abuse, and misinformation.

Systemic change is needed to end discrimination. Winning the ‘yes’ vote in the postal survey will not end homophobia and the campaign itself has given great licence for public homophobia, abuse, and misinformation. Rates of LGBTIQ people accessing mental health services have risen dramatically, though this also occurs around Pride and Mardi Gras, the vilification from the ‘no’ campaign is obviously having an extraordinary impact on exactly the people this campaign is alleged to empower and uphold. Referenda don’t change systems and yet the act of voting gives people the feeling of having made change. When that systemic change is not delivered it results in increased cynicism or even resentment towards the minorities who ‘mismanaged their opportunity’. Referenda are a dangerous delusion for both the good-willed majority and those who are personally affected.

Mary has said that these votes are opportunities to see what the public really think about an issue, unfortunately this assertion doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Australians are, by and large, still racist towards Aboriginal people and have no desire to compensate them, negotiate treaties, or regard them as sovereign entities who survived attempted annihilation. Research demonstrates significant and ongoing resentment towards Aboriginal people, especially if they have the temerity to assert their rights.

Mary Tomsic: Public votes can shine a light on important issues

I wasn’t wanting to argue that public votes reflect what people think about issues. What I want to suggest, rather, is that in examining the debates, campaigns and activities that accompany formal votes, we can see a range of ideas being expressed and that is what we should be attentive to.

I’m not sure we can ever know what the public really think. There is always an array of beliefs and ideas that circulate in the public realm – some voices are more strongly and forcefully presented than others, and some voices are silenced and ignored.

I entirely agree with you Hayley that the 1967 referendum did not end racism in Australia. But the history of Indigenous activism around this is important and the goals and desires of those working for constitutional change are significant, see for example, the activism of Joyce Clague and Faith Bandler on this, and other issues.

I also agree that the current non-binding postal survey will not end homophobia. Activist work against colonialism, such as the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, and homophobia/transphobia, such as Safe School Coalition, are examples where we can see people working for change, education and making public demands for people’s rights to be supported. I would much rather see government engaging with these types of activists, and others such as RISE (Refugees, Survivors and Ex-detainees) and Behind the Wire on people seeking asylum, to inform the stance they take. But this is not the type of action that those in positions of (party) political leadership tend to take.

Regardless of the ways in which I would like to see government lead and the types of social change I would like to see take place – what the current campaign around marriage equality does reveal to us what we already know, the homophobia and fear circulating in our society. It also reveals the status and desire for state sanctioned marriage for some LGBTIQ people. For example, looking at the Yes Equality campaign’s FAQs – they begin by saying ‘Marriage matters to Australian society. It is the secure foundation for loving, committed couples.’ Within this ‘lesbian and gay couples’ are privileged as they are identified as having rights denied. The statement on marriage continues: ‘that we value love and commitment and believe every Australian has the right to happiness.’ Coupledom, through marriage, defines happiness. Why should this be the case?

Regardless of the ways in which I would like to see government lead and the types of social change I would like to see take place – what the current campaign around marriage equality does reveal to us what we already know, the homophobia and fear circulating in our society.

During this current focus on a right to marriage, it is useful to pause and think broadly about the exclusions that come with the ‘no’ and the dominant ‘yes’ cases being made. Insightful reflections are needed now, such as one by Sophie Robinson on oral histories she conducted with lesbian activists, revealing the radical, intimate and political relationships lived and imaged by these women. Rather than confining ourselves within the bounds this exercise, a concern raised here by Hayley, we could use this moment to critically consider the terms of the debate. This would be a productive exercise for citizens to engage in, when thinking about their own rights and the rights of others.

One thought on “Voting On The Rights Of Others: A Debate”