What might we be overlooking when we analyse how the LNP’s youth crime fear campaign spread and took hold?

Elections are weird. Right until they step into the polling booth, a surprising proportion of voters are undecided, or at least open to changing their minds.

But although it’s possible to shift some voters late in a campaign, candidates are also operating in – and pushing against – broader, stronger currents that have been flowing and building momentum for months and years beforehand.

This year, the ‘crime is out of control’ current was stronger than I can remember for any previous Queensland election campaign. Labor made several good late moves, but had already lost too much ground in too many key swing seats, and the Greens also didn’t have a robust enough strategy to guard against the impacts of the youth crime fear campaign.

As The Guardian’s Ben Smee highlighted recently, Hansard records show that prior to the 2020 state election, the term ‘youth crime’ was only occasionally used in speeches in the Queensland parliament, but from around March 2021 onwards it began to be mentioned dozens of times a week, mostly by the Liberal National Party. This seems to have started just after Labor’s Youth Justice and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2021 proposed tougher restrictions on kids being released on bail, and gave police wider powers to search people without warrants – Labor’s targeting of young people may have opened up the political space for endless argument that further crackdowns were needed.

Throughout 2022 and 2023, ‘youth’ became a flexible, usefully-ambiguous word. The LNP’s proposed policy responses were mostly targeted at children, whereas many of the more sensational violent offences used to justify the proposed crackdown were actually committed by adults.

If we want to learn how to better push back against future fear campaigns, and effectively resist increasing persecution of vulnerable young people under the incoming LNP government, it’s worth examining a couple of important but under-acknowledged elements of how public discourse on youth crime was shaped over the past few years

The corporate media’s crime obsession wasn’t countered by more neutral reporting from other outlets

Profit-driven media companies fuelling crime paranoia to chase ratings isn’t new. I feel like it’s gotten worse in recent years, but it’s hard to say for sure.

At the same time as TV stations were cutting back on camera crews and field reporters, home surveillance systems have been proliferating. For mainstream media organisations, simply re-screening viewer-submitted CCTV footage of break-ins is much cheaper and easier than actual journalism (there’s some commentary and research that having more CCTV cameras in a community actually makes people more fearful; security companies actively promote fear of crime to sell products). The confluence of lots of recently-retired people learning how to use Facebook and turning online community groups into digital vigilante networks probably didn’t help.

Meanwhile, acts of domestic violence and abuse were essentially excluded from the anti-crime rhetoric, even though those offence categories are some of the only ones trending upwards.

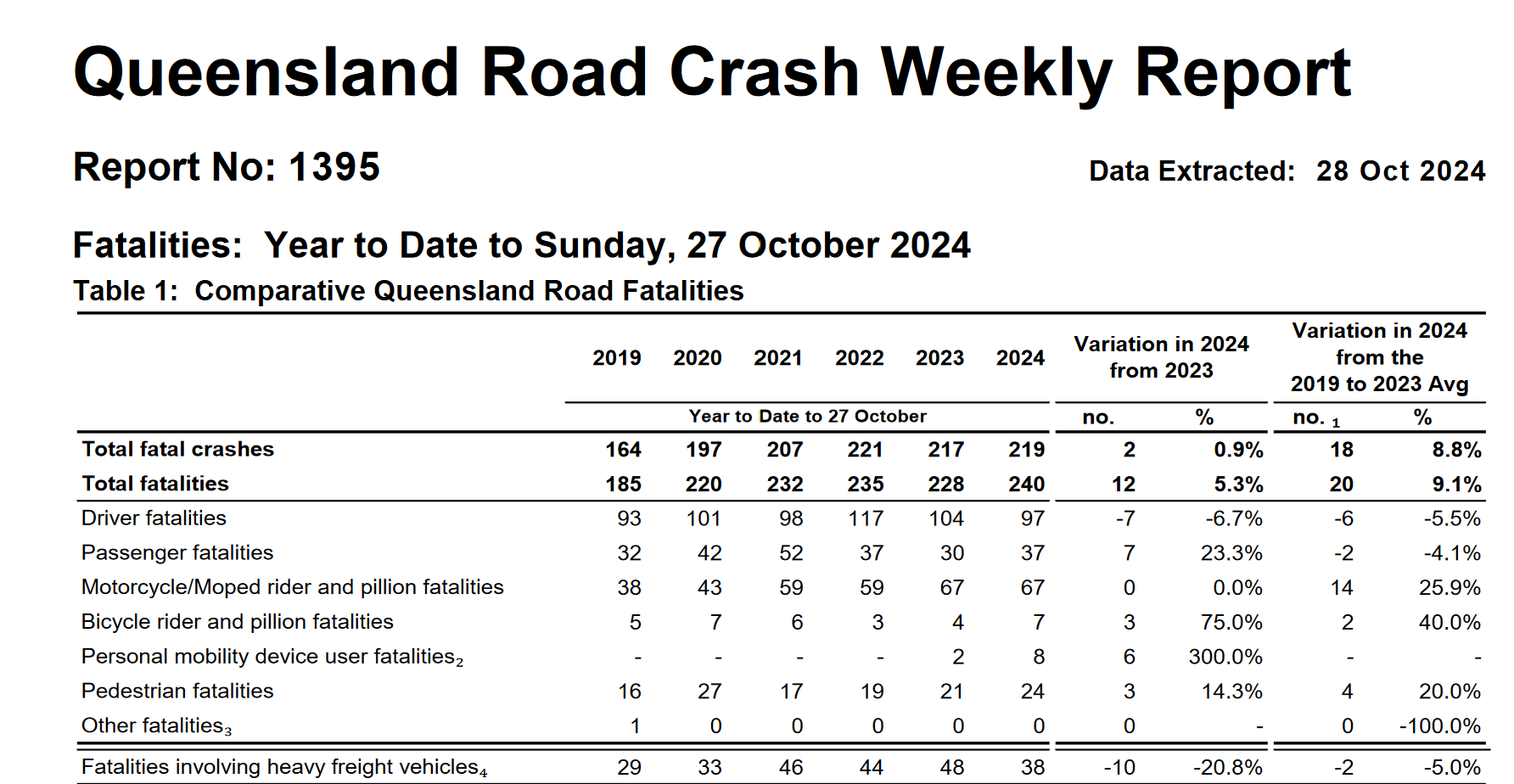

Queensland’s appallingly high road fatality rate was also left out of the conversation (except some specific tragedies involving stolen vehicles). Given that 240 people were killed in crashes (and a further 453 hospitalised) in this state from January to October 2024 (a much higher rate than NSW or Victoria), you’d think the driving offences involved might have formed part of the discourse on dangerous crime, but no.

In the media’s endless ‘special investigations,’ the small number of serious, tragic home invasions where people lost their lives were lumped in together with the higher (but still falling) rates of lower-level property crimes, so that anyone who’d ever had a car broken into or a parcel stolen from their front door might feel like they too had suffered some kind of near-death traumatic violation.

This discursive merging of lower-level theft, vandalism and car-jacking with serious violent assaults and homicides under the amorphous ‘youth crime’ catchall seems to have been a key factor behind the fear campaign taking hold. It was difficult to talk sensibly about broad statistical trends without being accused of ‘disrespecting’ people who’d lost loved ones in the rarer examples of more serious violent offences.

But crucially, with a few notable exceptions, such as this April 2024 article by ABC journalist Kenji Sato, and several pieces from the Guardian, there was no significant pushback against the latest wave of youth crime paranoia from other sections of the media. I haven’t had much faith in the ABC ever since they unapologetically spread bare-faced lies about fictitious pedophile rings that became the basis for John Howard’s NT intervention (check out Amy McQuire’s excellent book Black Witness for more on this). But even I was surprised when ABC ran embarrassingly simplistic, sensationalist stories like this 7:30 report feature from August 2024 (don’t waste your time watching the whole thing)…

It featured 7 whole minutes of Current Affair-esque melodrama about stolen cars, followed by barely 90 seconds at the end from a lone youth worker emphasising that ‘tough on crime’ responses don’t work. To back up the ‘youth crime is a growing concern’ narrative, the story uncritically regurgitated some rough police figures stating that the ‘total number of offences’ (a category which includes everything from shoplifting to domestic violence) in Townsville had risen slightly in recent years, without adding the important context that Townsville’s total population has also risen significantly over the same time period.

It was garbage reporting from the ABC, particularly in a context where per capita rates for most offence categories in Queensland have been dropping consistently. Reports like this muddy the waters, throwing off people who might otherwise push back against the fear-mongering from outlets like channel 7 and channel 9.

It was really only in the last week or two before election day that I noticed a few stories and radio packages emphasising that a) the actual hard data doesn’t support claims of a youth crime ‘crisis,’ and b) being ‘tough on crime’ and locking up more kids doesn’t actually help anyway. If more TV and radio stories had been offering this perspective 6 or 12 months ago, Crisafulli’s ‘adult crime, adult time’ nonsense probably wouldn’t have cut through and taken hold as strongly, but the counter-narrative emerged too late.

Labor didn’t push back when they should have

While outlets like the ABC failed to counter-balance the corporate media’s ‘youth crime crisis’ narrative, Labor itself also dropped the ball by acting as though the issue was real.

If crime rates are dropping, but a large chunk of the public feels like they’re rising, signalling that you’re ‘taking the issue seriously’ and will be making changes to address the fictitious problem is a diabolically stupid political strategy for a governing party. But Labor not only accepted the false premise that youth crime was a rising problem – they doubled down and adopted even more of the changes the LNP were advocating.

Under the Palaszczuk/Miles Labor government, Queensland was locking up significantly more young people than most other states. In fact, almost 1/3 of child prisoners across the country are incarcerated here in Queensland (and over 60% of child prisoners are Indigenous). Perhaps even more shockingly, approximately 88% of these children haven’t even been sentenced for a crime – they’re just waiting to go through the court system, meaning that many are locked up for prolonged periods when they haven’t even been found guilty in a court of law.

Basically, Queensland Labor had already been deploying ‘tough on crime’ policies and rhetoric for years. In doing so, they further legitimised claims that crime was worsening andthe idea that prolonged incarceration was an appropriate and effective response to youth offending, even though all the expert evidence says otherwise.

There’s a lot more to be said about how unstrategically Labor responded to the growing campaign, particularly its inept response to the August 2023 ‘Voice for Victims’ rally (side note: I’ve never seen such a tiny rally attract so much positive media coverage).

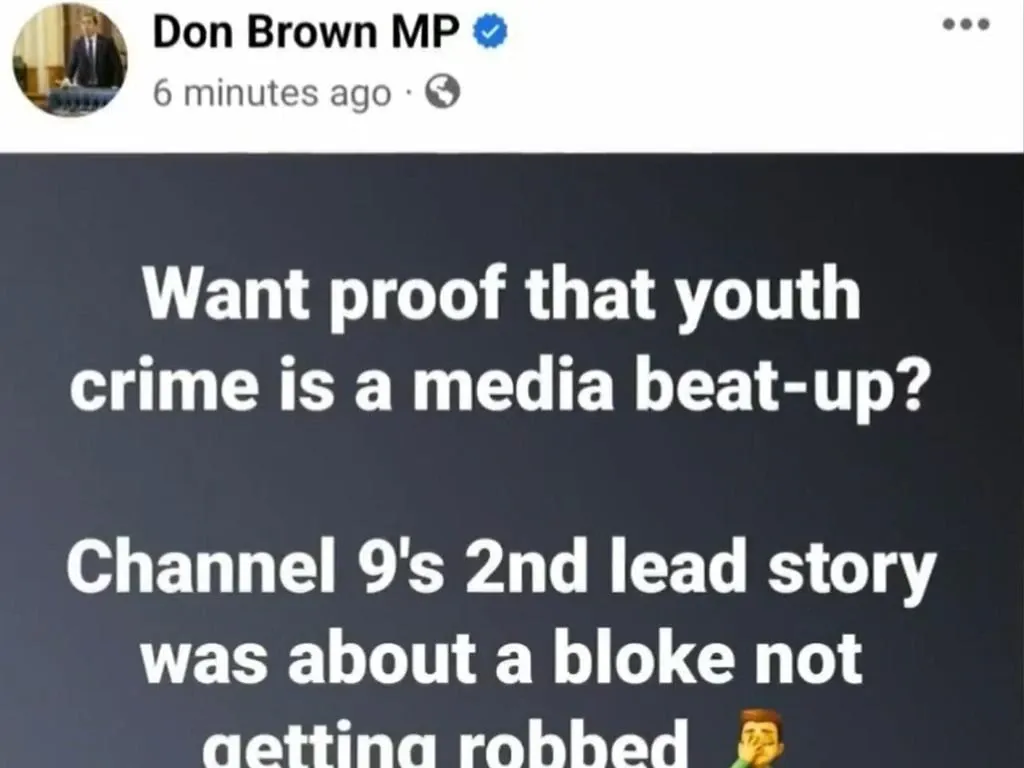

But an interesting moment that stands out to me was Labor MP Don Brown’s lone warrior attempt in late August 2023 to call out the scare campaign for what it was.

While I give Don props for at least attempting to challenge the dominant discourse, his single, laconic Facebook post wasn’t supported by a more coordinated and unified messaging strategy from the Labor machine. Rather than then agreeing to a stitch-up interview with channel 9, he should have lined up a longer-format live interview with ABC radio or another more sympathetic outlet. As it was, he pissed off a lot of people, pouring more fuel on the LNP’s scare campaign rather than neutralising it.

By late August last year, the ‘realness’ of youth crime was so widely accepted that explaining it was a beat-up and a scare campaign required more nuance and political deftness than one Labor MP’s short, easily-mischaracterised Facebook post criticising an individual media company’s reporting of a single story.

If Labor had instead carefully prepped the media and the wider public with facts and figures, gradually built the argument for why the scare campaign shouldn’t be further legitimised, and maybe even tried to humanise some of the very small number of young people who were committing serious offences, perhaps they could have prompted a more balanced discussion.

A strategic way to do this would’ve been to platform ordinary people who were sceptical of the ‘crime is out of control’ narrative, to let them lead a conversation that Labor MPs themselves would’ve been attacked for starting. This wouldn’t have neutralised youth crime as an election issue altogether, but it might have at least prevented it becoming the issue.

Instead though, the Labor government distanced itself from the Capalaba MP’s Facebook post, essentially signalling that they did not agree with him that youth crime was a beat-up, and ceding that field of debate altogether.

Maybe I’m over-stating the significance of this episode, but it felt like a crucial moment that shaped how the major parties dealt with the issue going into 2024.

The Greens tried to stay out of it altogether

While Labor half-heartedly attempted to convince voters it was just as tough on crime as the LNP were, the Greens effectively vacated the debate. It seems that the default guidance to key candidates from the party’s statewide campaign committee was to avoid proactively commenting on youth crime at all.

If voters brought up the issue, then campaigners would of course talk about it. But Greens spokespeople weren’t sending out media releases, drafting socials posts or handing out flyers that articulated the Greens view on the matter.

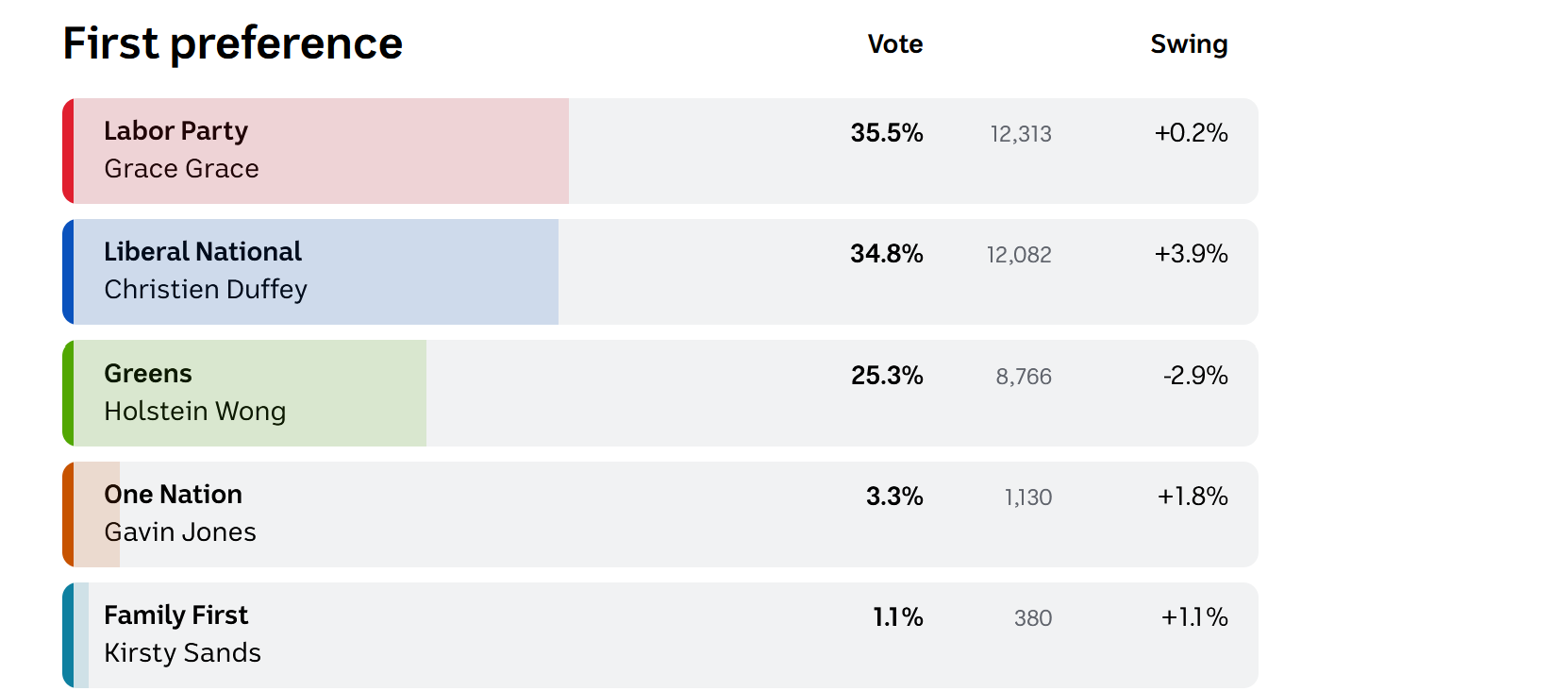

Maybe power-holders within the Greens assumed youth crime was only a concern for Labor-LNP swing voters, and that Greens supporters were less susceptible to sensationalist fear-mongering. But the swing from the Greens to the LNP in seats like McConnel suggests otherwise.

Although I don’t think this was the right approach, I can see why Greens campaign managers adopted it. As a general rule, the more politicians talk about an issue, the more fodder they give the media, and the more seriously the public takes it.

I can imagine the quandary the Greens were grappling with…

- if you proactively say “Here’s how the Greens would address youth crime…” you’re still signalling to the wider community – including your own support base – that it is an important issue, further fanning the scare campaign’s flames

- but if you state directly that it’s a scare campaign and that conservative politicians are just whipping up fear to win votes, you can’t guarantee that the nuances and caveats of your message will be retransmitted, and could end up seeming ‘insensitive’ and pissing off a lot of people who have been negatively impacted by crime (as happened to Don Brown)

Unfortunately though, when the mainstream media, both major parties, various other vested interests and a whole bunch of ordinary people on social media, are all acting as though youth crime is the big election issue, a choice by the Greens not to talk about it doesn’t change that. It simply diminishes the Greens’ political relevance, and means the party isn’t offering its supporters a meaningful alternative diagnosis and narrative that they can use in conversations with friends and family to rebut and challenge the fear campaign.

But there was also another more significant force at play, helping build youth crime paranoia across the state, perhaps even more effectively than the media and the LNP…

Queensland Police as shapers of public opinion

Police have always worked hard to legitimise their own existence. You can’t get away with routinely violating people’s autonomy and systematically using violent force to boss people around unless you spend a lot of time and money convincing the public that they need you. There’s a rich body of research and theory examining the modern role of copaganda. For a good introduction to the topic from an Australian angle, I particularly recommend this recent webinar organised by Radio Reversal (Radio Reversal will soon be publishing a full podcast series on colonial copaganda, featuring some excellent interviews with people like Ronnie Gorrie – sign up to their Substack for updates on that).

The more the police talk publicly about crime, the more concerned some people will become about it.

Beyond the intentional copaganda and the QPS’s large PR team (which I’ll come back to), I wonder how much this is also a matter of human to human relationships.

Numerically speaking, Queensland’s police force is larger than ever. That doesn’t just mean more cops out on patrol causing/looking for trouble. From what I observed in my 7 years as a city councillor, it means more officers making presentations to local neighbourhood watch groups and rotary clubs, handing out awards at school assemblies, hosting ‘coffee with a cop’ sessions, or running info stalls at community festivals. I imagine it also means that more people who are employed by QPS are personally enmeshed in local community networks, sharing a beer with mates at Saturday arvo BBQs, picking the kids up from soccer practice, posting opinions on social media, and calling in to talkback radio.

In both semi-public community spaces like P&C meetings, and especially in one-on-one conversations, I’ve noticed cops often freely share their personal opinions about government policy – seemingly less reservedly than most public servants. Most coppers seem very loyal to the institution of policing, but not particularly loyal to the government that employs them (especially when Labor is in power).

Cops obviously see and hear about lots of crime – including some pretty shocking and traumatising stuff – so unsurprisingly, many tend to over-estimate how high crime rates are. From the conversations I’ve had with officers over the years, many seem to feel quite powerless; they only have a narrow range of (mostly oppressive) tools to respond to the symptoms of a broken, unjust society.

Officers’ views are also shaped by their police union, whose myopic mantras are effectively that ‘police need more power’ and ‘tough on crime works.’ So we can guess what kinds of ideas many cops would be sharing with their communities about youth crime. We don’t know exactly what impact all this is having on public opinion, but it’s worth thinking about. We’re potentially talking here about several thousand officers out in society, regularly telling their friends and acquaintances that youth crime is rising and that young offenders ‘have it too easy.’

Beyond that, there’s a much wider web of prison guards, prosecutors and even youth workers who are all cogs in the prison-industrial complex, and whose jobs are essentially more secure when the government is locking up more kids. What stories and policy responses might they be sharing with their networks?

Aside from this on-the-ground influence, QPS as an organisation also has huge media/PR reach. Yuin researcher Associate Professor Amanda Porter suggests that the Victorian Police employ 99 staff in their media unit. The exact number employed by Queensland Police’s media team doesn’t seem to be publicly available, but I’d estimate it’s at leastseveral dozen full-time employees. That’s a lot of PR staffing capacity.

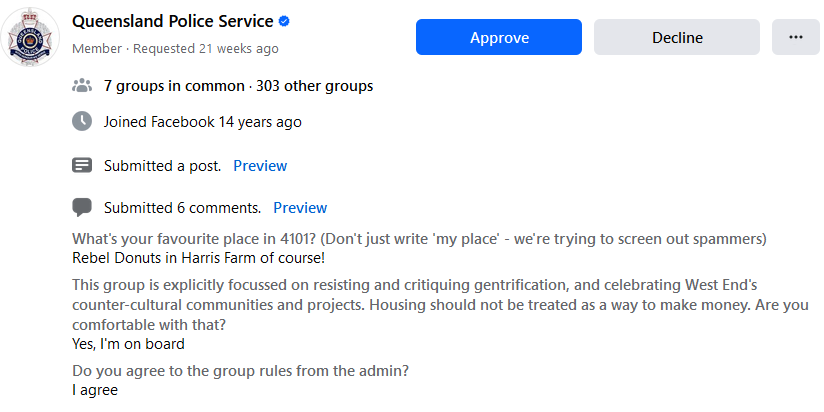

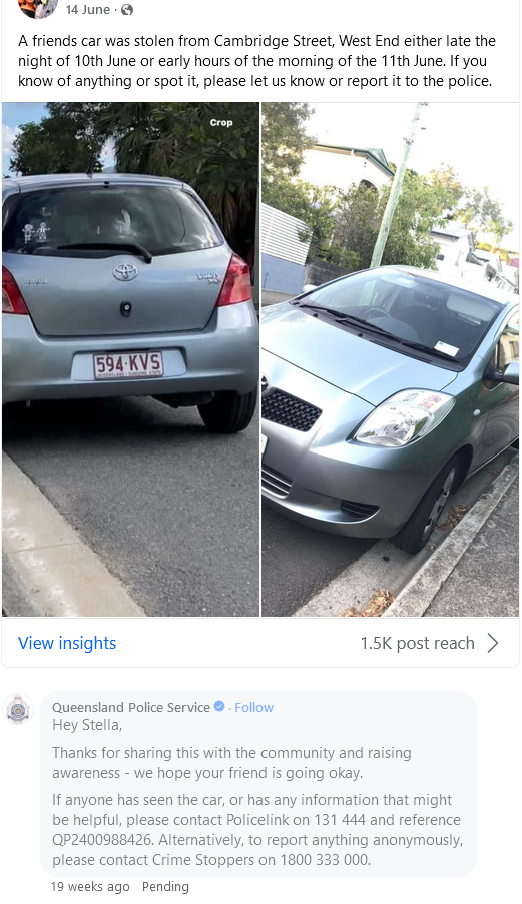

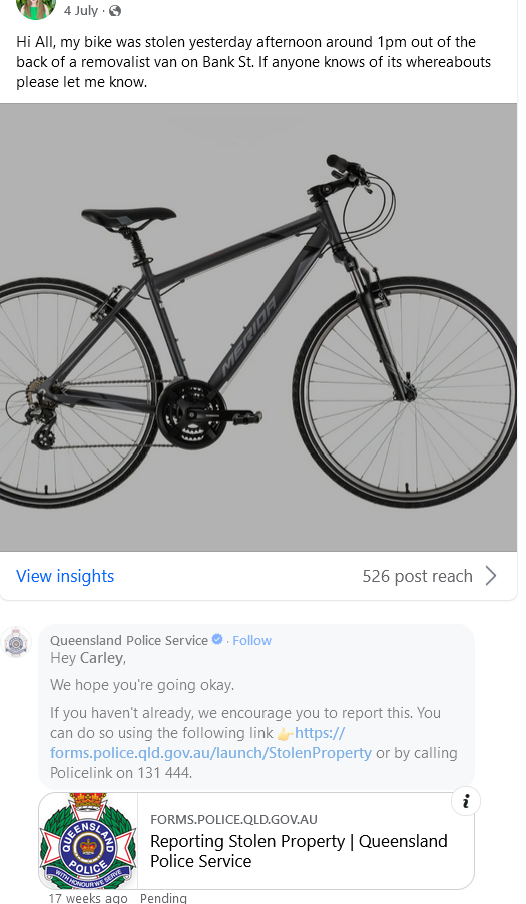

Last year I was interested to see the official Queensland Police Service Facebook pagetrying to join a local suburban community group I help moderate. The posts they’ve attempted to make vary from light-hearted comments that seek to build rapport with the community, to replies to stolen property posts encouraging residents to make formal reports.

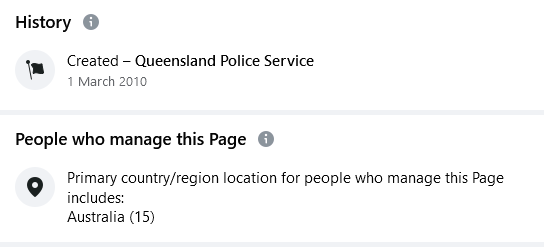

The Queensland Police Service’s public Facebook page appears to have 15 separate Facebook user accounts managing it – it’s possible some of those 15 accounts are shared between multiple individuals, but even 15 staff managing one Facebook page is a lot (if anyone knows more about QPS media staffing capacity, please email me at office@jonathansri.com). The page has joined over 300 Facebook groups, with employees presumably making similar posts in online community spaces across the state. All QPS social media channels have massive public followings, but this degree of responsiveness and group-based engagement reflects a very well-resourced social media team.

But QPS media isn’t just spreading copaganda on social media. They’re continually briefing journalists and sending out media releases about crime. No matter the time of day, if a time-poor reporter wants extra content to fill a story quota or news bulletin, police media have stories ready, and can happily provide stats, photos and video footage at short notice. The relationship between police and the mainstream media is very cosy, and includes swapping exclusive tip-offs in exchange for positive coverage about policing (I’ll have to write a separate article about this sometime).

Police aren’t just publishing social media posts, calling press conferences and pushing stories on journalists that shape the general public perception of rising crime. They also have the resources to produce their own authoritative-looking, long-form video content. Check out this piece of copaganda (the first 90 seconds is enough to show what impression most viewers are going to take away from this)…

A 31-minute ‘documentary’ titled ‘Policing Young Offenders,’ published on the Queensland Police Youtube page and other channels in May 2023, features heaps of sensational bodycam and dashcam footage, emotive backing music, high-quality motion graphics, and carefully-curated interviews with QPS and youth justice department employees. The video’s target audience isn’t young offenders themselves – it’s pitched directly at people who are already concerned about youth crime.

To be fair to the team that produced this, the documentary does offer the message that “you won’t arrest your way out of this” and that we also need to understand the factors which contribute to young people offending in the first place. But that angle is lost under scary, shocking footage of burning cars, teens getting handcuffed, and interviewees’ stories about ‘youth offenders’ behaving badly. Eight and a half minutes in, the doco very brieflymentions that ‘youth offender’ numbers in Queensland are actually trending downwards, but doesn’t really bother explaining how contemporary concerns about youth crime are a political and media beat-up.

Interestingly, the documentary ends with a whole section of positive commentary on new legislation that expands police powers, and the subtle implication that more ‘tough on crime’ law changes might be needed. There is no direct mention of the kinds of housing, education and healthcare policy changes that would actually help marginalised young people.

Whatever its director’s intentions actually were, public relations exercises like this function to entrench and legitimise the narrative that youth crime is a serious and growing problem, and that police are doing an effective job to curtail it but they need more resources and powers. It’s unusual to see such a high-budget, government-funded production (much more in-depth than just short clips for social media) seeking to shape public sentiment and explicitly comment on government law-making. QPS certainly hasn’t produced any similar 30-minute documentaries about domestic violence or how many people the car industry is killing each year.

If we are to properly theorise how public sentiment – and thus policy-making – on issues like so-called ‘youth crime’ is shaped, we have to recognise that police themselves are also playing a very active political role in guiding public opinion, and arguably have far more reach and influence than most other political actors.

The right lessons?

On the morning after the election, lawyer Debbie Kilroy tweeted poignantly,

“In the end, it was all about our children: feeding them or locking them up.”

This comment really resonated with me. But I have to concede it’s not really how the campaign played out.

Maybe the result could have been different if Labor and the Greens had contested the election on those terms, taking the youth crime debate head-on and directly juxtaposing carceral punishment responses against compassion and rehabilitation. But the Greens didn’t assertively challenge the LNP’s narrative. And Labor was locking up kids too (half-copying the Greens’ free school lunches policy was a fairly late-stage announcement).

For those of us who don’t want to see more kids locked up, the over-arching lesson here is that once something becomes a major issue of concern for a large proportion of the population, not talking about it doesn’t diminish its currency. We have to recognise that it’s not just the LNP single-handedly stoking such fear campaigns. The significant reach of other well-resourced entities like the police themselves means we have to counter these narratives early, robustly and tirelessly, rather than ignoring them and hoping they’ll lose steam by themselves.

Jonathan Sriranganathan is a writer, musician and community worker who was elected back in 2016 as Brisbane’s first ever Greens city councillor, representing the Gabba Ward on the city’s inner-south side. Jonno stepped down from the council in April 2023, after 7 years of service in that role. In March 2024 Jonno was the Greens candidate for Mayor of Brisbane in the local government elections.

This article was originally published on Jonathan Sriranganathan’s blog. You can support Jonathan’s writing by subscribing to his blog.

Image credit. Brick Wall by Dean Hochman, 2025, CC BY 4.0.