The Dilemma of Care for Radical Social Workers

In the capitalist countries a multitude of moral teachers, counsellors and ‘bewilderers’ separate the exploited from those in power… the intermediary does not lighten the oppression, nor seek to hide the domination; he shows them up and puts them into practice with clear conscience of an upholder of peace; yet he is the bringer of violence.

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

The task of social justice is what led me to practise as a social worker. I feel enormously privileged to do the work that I do, and believe (perhaps because I must) that I make some small difference. Nonetheless, it would be an act of willful prevarication to claim that we have a structure of care that works for all involved. Indeed, it appears to function neither for workers nor for people accessing services. Despite clinical workers fighting hard under trying circumstances, the systemic features that keep people in distress remain.

I believe that social work can be salvaged from the lure of professionalisation and acknowledge the ways in which ‘care’ is used as a tool for social control. I also want to draw attention to the alternative ways of doing care as well as making changes that have grown out of necessity in our fragmented polity.

In this piece I want to present a way of thinking about social work that acknowledges an inherent contradiction that is a feature for many of us who work as agents of the state –the dichotomy between the desire to provide care with the necessity to impose control. I take as a basis for this the premise that social work has been complicit in the project of dispossession of First Nations sovereignty in Australia. I then want to engage with the problem of confronting control that faces social workers seeking to work towards radical change. Finally, I am seeking to provide examples of different ways of conceptualising care that is ‘de-professionalised’, to suggest a theory of change to allow social workers to engage with social change beyond the restrictions placed on us in our professional roles, and look to a future of care that preserves autonomy and dignity.

Enlisting a charity model in the colonial project

Social work is characterised by a dissonance between care and control. Its earliest antecedents in the Charity Societies of the industrial West made a distinction between the ‘deserving’ poor, who should be provided with material relief, and the undeserving, whose condition was caused by moral failure. Others took a different approach, the proto social workers of the ‘settlement houses’ movement sought to embed themselves within marginalised communities, living and working among people with whom they would share skills and resources. The industrial conditions of 19th century capitalism forced people into outright misery, which led to a critical mass without much to lose, a danger for the ruling class. Both charity, with its emphasis on individualised support, and community development, if divested of its political implications became then a useful tool for the expansion of control amongst potentially dangerous and certainly inconvenient groups.

Extracting the consent of the ungovernable has been a task of the state which enlists social workers. As part of the colonising project Irene Watson argues that Terra Nullius constructed a ‘civilising mission’ for invaders of this continent to ‘close the gap’ between native peoples who lived in an abject squalor of their own ignorance and heroic colonisers who would show them the way. It is admittedly difficult to quantify but it has been documented (and acknowledged by the national organisation representing them) that social workers were involved in the removal of children in the Stolen Generation.

This is hardly unique in Australia, social workers in every settler colonial state have been complicit in the cultural genocide of First Nations peoples through the ‘protection’ and removal of children and the provision of paternalistic welfare initiatives. I think the universality of social work in the history of First Nations genocide reveals its role as a tool for the larger project of white supremacy and colonial dispossession. This should encourage social workers (indeed, everyone) to take a highly sceptical view of arguments that justify practices that deprive human beings of rights ‘for their own good’. For this reason it is important to consider the broader structural dynamics within the provision of care.

Capital needs victims. An adversary against which it proves triumphant. Its adversaries are ‘public secrets’, experienced by all but denied through surveillance, self-censorship and when required, violence. These experiences are a consequence of a mode of economic organisation built on extraction and dispossession. Mental illness is a natural outcome of these forces. Structural factors that may contribute to depression, anxiety, trauma, ‘disorders’ writ large, are obfuscated in mainstream psychiatry. These secrets are enforced through the narratives of social progress, personal enrichment, and self-care.

To take the example of a TED Talk emblematic of this narrative, the speaker argues that the problem with modern culture is ‘too much sitting’ and if only people would walk when having meetings, all manner of health risks would be resolved. Psuedo-science quackery provides individual marketable solutions that pose no challenge to existing systems and make us feel as though it is our obstinate lack of personal enterprise that causes us to feel pain, stress and misery.

Facing uncomfortable realities: the threat of professionalisation to critical practice

In response to these contradictions, social worker Chris Maylea argues that the profession ought to be abolished altogether. In spite of the invocation of progressive change advocated by the radical and critical amongst the ranks of the profession, social workers have thus far been unable to challenge institutional power in lasting ways. Maylea takes an impossibilist position in arguing that ‘helping people exist in an unfair system’ perpetuates the system. Additionally, social workers who seek to engage with grassroots movements from their positions of power risk de-radicalising those movements or co-opting them back into the project of the state. Indeed that leadership within social work has pursued a managerial hierarchical structure incompatible with the redistribution of power which social workers seek to further.

Of particular concern to Maylea is the ongoing use of restrictive treatment within the mental health sector. He argues that involuntary treatment is viewed as a ‘regrettable necessity’ by social workers without reflecting on the deprivation of human rights it entails. Ultimately for Maylea, social work is a lost cause and attempts to revive it are a waste of energy which would be better spent in other avenues of social change.

The State of Contemporary Care Services

The current crisis within the mental health system reveals the challenge of change from within. The Royal Commision into Victoria’s Mental Health System is not a radical document, yet reveals glaring gaps in providing treatment. In particular lack of community engagement and poor integration with other health services (like drug and alcohol services). Strikingly, there is also a lack of engagement from people who receive these services.

The Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council (VMIAC – the peak body for people with lived experience of mental health treatment) publishes regular reports on restrictive practices which show increases in mechanical restraint and seclusion in the most recent reporting period. These practices are especially prominent in their disproportionate use on First Nations people, who incidentally also have disproportinately high rates of mental illness and death by suicide. While the Royal Commission and VMIAC, both critiques from outside the health system itself, show there is some hope in the project of reform to reduce perhaps the most controversial of these practices and pay at the very least some lip service to the lived experience of those subjected to them, the task of change ‘from within’ remains dubious. The ability for workers to advocate for change is also hamstrung by the restrictions placed on them by their own positionality.

Avoiding the dissonance is dehumanising

Social work organisations, in the quest for legitimacy, have taken on a ‘professionalising agenda’ that contributes to elitism in social work, protecting ‘specialised knowledge’ of ‘scopes of practice’. This separates social workers from the people they work with and obfuscates their own position as proletarians who are enlisted in the unpleasant task of a controlling agenda, isolating the exploited from those in power. It would be crude to compare the role of the social worker to the role of the counter-insurgent, however I would draw attention to the civilising of dissident populations which it implied in this relationship and the underlying violence that accompanies it.

Paulo Friere shows that in this relationship (in his case teacher-student, perhaps for us clinician-patient) both parties are deprived of the full experience of humanity. By transforming the relationship into one in which knowledge/experience/care flows in both directions a mutuality is established that preserves the dignity and humanity of both parties and opens up a space for new possibilities.

It is worth exploring for a moment the ways in which this is occuring. At the moment, contemporary mental health practice (in theory) places emphasis on what is called the ‘recovery model’. This is the theory that there is no one treatment that is suitable for everyone, and that people who use services are experts on their own experience. The implications of this have led to a strategy to embed ‘lived experience’ workers within organisations. Both at the level of governance and at a direct service provision level.

The critique that I would bring to this particular model is twofold: firstly, the actual power dynamic within services is unchanged. While the presence of a consultant who is an advocate for people who access services (most often termed as ‘consumers’ by organisations) brings a valuable perspective and a level of accountability to decision making, this does not amount to a democratic reformulation of health services. The second point is that as lived experience workers are often cheaper alternatives in direct service provision, the potentially critical role that they play risks being co-opted by a state primarily driven by the bottom line. This is argued by Helena Roennfeld and Louise Byrne, who suggest a process of professionalisation of lived experience work that parallels that of social work which I have raised here.

In the next part of this essay I would like to suggest some alternative models of care that I think contain a mutuality we can learn from.

Acknowledging the reality and necessity of ‘care work’

The reality is that many people from marginalised communities are in fact denied care altogether. When care is provided it often has ‘strings attached’. The Community Development Program (a ‘workfare’ arrangement aimed at remote communities) and Cashless Welfare Card are both examples of welfare policies that were implemented in ways that targeted First Nations people and exposed affected communities to exploitation, again under the auspices of providing material aid. The National Disability Insurance Scheme was established to provide choice and control to participants but often requires prohibitive requirements and hurdles to prove and maintain eligibility. Meanwhile Medicare continues to buckle under the weight of inflation resulting in those unable to pay for healthcare subjected to extended wait times for appropriate treatment.

These snapshots show not a set of coincidental policy failures, but a care economy that is designed to run on crisis, that is designed to be ‘broken’. The dignity of those who are asking for support is not of paramount importance within a capitalist healthcare and welfare system.

Within the cracks of a broken system, care grows out of necessity. Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, an activist and organiser in radical spaces at the intersection of queerness, disability and race, describes ‘webs’ of care that are created amongst people who have been systematically excluded from the charity model. This kind of care is actually the kind of care most people are familiar with in their everyday life. People bound by obligations of one kind or another (often family/blood-ties) providing direct physical and emotional support to one another. Crucially here, Piepzna-Samarasinha writing from a queer perspective points to the fact that the care they are describing is based on a mutuality that does not confer “moral superiority of the giver over the receiver” that is characteristic of the charity model of care.

This is not to unreasonably glorify the emergent strategies of those who are excluded from accessing the resources that many of us take for granted, and it is important to recognise the power dynamics inherent in a relationship where the people do not share the same experiences and privileges that may come from race, gender, class, education, income, sexuality, dis/ability. Nonetheless, the privileging of professionalised forms of care brings with it a disregard for the way people care for one another on a day to day basis.

In the hegemonic model of healthcare, trauma, outrage, grief, pain, and fear are often framed as individual disorders requiring treatment. This point should be clarified, these experiences are framed as disorders to the extent that they result in dysfunction, that is defined by the inability to comply fully with societal expectations and cultural norms. Often though, these experiences are not individual failings, but are shared by communities that can be powerful points of connection.

The AIDS Coalition To Unleash the Power (ACT UP) group was formed in the United States in the 1970s. This group engaged in direct action against price gauging by pharmaceutical companies, protests against police brutality and sex-positive propaganda. The Chicago chapter of the group also built mutual aid into its organising model through a Committee for Sustainable Activity and Care to support activists that were part of a community deeply affected by shame, illness and discrimination.

The Jane Addams Collective’s analysis of this group goes on to suggest that trauma is itself a tool of the state and its intermediaries to prevent the empowerment of communities repeatedly subjected to violence and marginalisation. Speaking at a rally in Washington activist and filmmaker Vito Russo said “I intend to be alive to kick the shit out of this system so this will never happen again”. Individuals and leaders burn out, get sick, need care themselves sometimes, ACT UP emphasised the importance of resilience and mutual aid became a ‘weapon’ that gave their actions power.

Workers and patients can also come together over shared issues. Psychologist Sanah Ahsan, has worked towards decolonising mental health practice and utilising an approach to psychology that promotes liberation of people and communities. She has recently called for a rethinking of mental health along the lines of structural change. After all, workers who come into the workforce with a desire to help others are often frustrated about the institutional barriers to doing so, and they themselves may have lived experience of mental illness and substance use. Additionally those receiving mental health treatment bring an enormous amount of patience and resilience from navigating a bureaucracy, as well as a diversity of life experiences, talents, and perspectives that are missing from mainstream healthcare.

The Mental Patients Union was founded in London following publication of the Fish Pamphlet in 1974 which combined a Marxist Analysis of mental illness with demands for dignity and autonomy in treatment, but also broader demands for housing, employment rights and the eventual abolition of hospitals. The Union itself was founded by workers and patients at the hospital and distributed documents about medication side effects (which were otherwise not commonly being disclosed by professionals), and representation for people at mental health tribunals which governed compulsory treatment outcomes. Members of the union reported the experience of getting organised as a ‘jolt’ that allowed them to begin to make connections and recognise their own strengths.

Rather than abolishing social work, perhaps it can be made obsolete. Wolfgang Huber who founded the German Socialist Patients Collective (SPK) wrote of the ‘social work function’ that emerged in the collective. Denied funding for a professional social worker by the administration at the University Hospital they were based out of, Huber notes that the role of the social worker (assisting with housing, relationships, education) was distributed throughout the members of the collective. The social need for such a role remained, but by necessity it became a task performed collectively.

Similarly the Transformative Justice movement aims to address the problem of interpersonal violence outside of the structures of police departments and prisons. Organiser Ejeris Dixon notes that it is not enough to have a strong political analysis about police abolition or a desire to do good, but that community safety is a constant project of building and sharing skills ‘slowly and deliberately.’ She critiques a model of care that can be packaged and sold without the process built over time and that is dominated by individual experiences.

Movements such as these demonstrate the importance of building connections and sharing skills that can occur within existing systems. In trying to do something different, and learning from the experiences, new alternatives are able to emerge. Part of that for us as social workers is not to act as though we have all the answers, or to act as though we can’t see the ways in which society disempowers the people we work with, so commit to the task of learning from others and to be open to the potential for transformation.

Concluding remarks

Care is completely devalued, unpaid, and unacknowledged most of the time. Yet the care that is provided by the state or its intermediaries, is sanctified as the domain of the rarified professional elite.

Of course, we join these professions out of a desire to ‘do good’, but find ourselves, under the auspices of this maxim, working within oppressive structures. These structures may deprive human beings seeking care of joy, autonomy and dignity. We, as lanyard wearing ‘do gooders’ may find it a comfort to retreat into professionalism to avoid this dissonance, but in doing so find ourselves isolated from the communities in which we work, and perhaps from the willingness to seek care ourselves.

I fumble around with this question every day in my experience as a social worker in the public mental health system. This is a location of dissonance, and I believe, a site of contest between a hegemonic model of care and the care that emerges in the cracks of its own inconsistencies.

References

Ahsan, Sanah 2022 ‘I’m a Psychologist – and I Believe We’ve Been Told Devastating Lies about Mental Health’ (retrieved from www.theguardian.com 07/09/2022)

Dittfield Tanja 2020 ‘Seeing White: Turning the Postcolonial Lens on Social Work in Australia’ Social Work and Policy Studies 3:1 1-1

Dixon, Ejeris and Piepzna-Samarasinha 2020 Beyond Survival: Strategies and from the Transformative Justice Movement AK Press Chico

Fanon, Frantz 2001 Wretched of the Earth translated by Constance Farrington, Penguin Group, London.

Friere, Paulo 2017 Pedagogy of the Oppressed translated by Myra Bergam Ramos, Penguin Group, London.

Garrett, Paul Michael 2021 ‘A World to Win: In Defence of (Dissenting) Social Work – A Response to Chris Maylea’ British Journal of Social Work 51 1131-1149.

Garret, Paul Michael 2021 Dissenting Social Work: Critica; Theory, Resistance and Pandemic Routledge, New York.

The Guardian 2008 ‘A Crusade for Dignity’ (retrieved from www.theguardian.com 18/08/2022)

The Guardian Australia 2022 ‘Restraint of Victorian Children in Mental Health Facilities Increases by 32%’ (retrieved from www.theguardian.com 18/08/2022)

Huber, Wolfgang 1972 Turn Illness Into a Weapon TriKont-Verlag, Munich.

Institute for Precarious Consciousness 2014 ‘We Are All Very Anxious: Six Theses on Anxiety and Why it is Effectively Preventing Militancy, and One Possible Strategy from Overcoming it’ (retrieved from theanarchistlibrary.org 18/08/2022)

Jane Addams Collective 2018 “Mutual Aid, Trauma, and Resiliency” (retrieved from theanarchistlibrary.org 18/08/2022)

Land, Clare 2015 Decolonising Solidarity: Dilemmas and Directions for Supporters of Indigenous Struggles Zed Books, London

Maylea, Chris 2021 ‘The End of Social Work’ British Journal of Social Work 51 772-789.

Morgenshtern, Marina 2022 ‘Interrogating Settler Social Work with Indigenous Persons in Canada’ Journal of Social Work 22:5 1170-1188

Pease, Bob; Goldingay, Sophie; Hosken, Norah; Nipperess, Sharlene (eds) 2016 Doing Critical Social Work Arena Books, Crows Nest.

Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi 2020 Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice Arsenal Pulp Press, Vancouver.

Roennfeldt, Helena and Byrne Louise 2021 ‘Skin in the Game: The Professionalisation of Lived Experience Roles in Mental Health’ International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 30:1 1445-1455

Scanton, Edward and Harding, Scott 2006 ‘Social Work and Labor Unions’ Journal of Community Practice 13:01 9-30.

Snook, Veronica 1984 ‘Burnout- Whose Responsibility?’ Australian Social Work 37:2 19-23.

Spander, Helen 2006 Asylum to Action: Paddington Day Hospital, Therapeutic Communities and Beyond Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London.

Watson, Irene 2015 Aboriginal Peoples, Colonialism and International Law: Raw Law Routledge, Oxon.

Matt Rogers is a social worker working in the mental health sector. He lives and works in so-called Melbourne. He became a social worker after being involved in the environmental movement and is an active unionist. In his spare time he pampers his cats rotten.

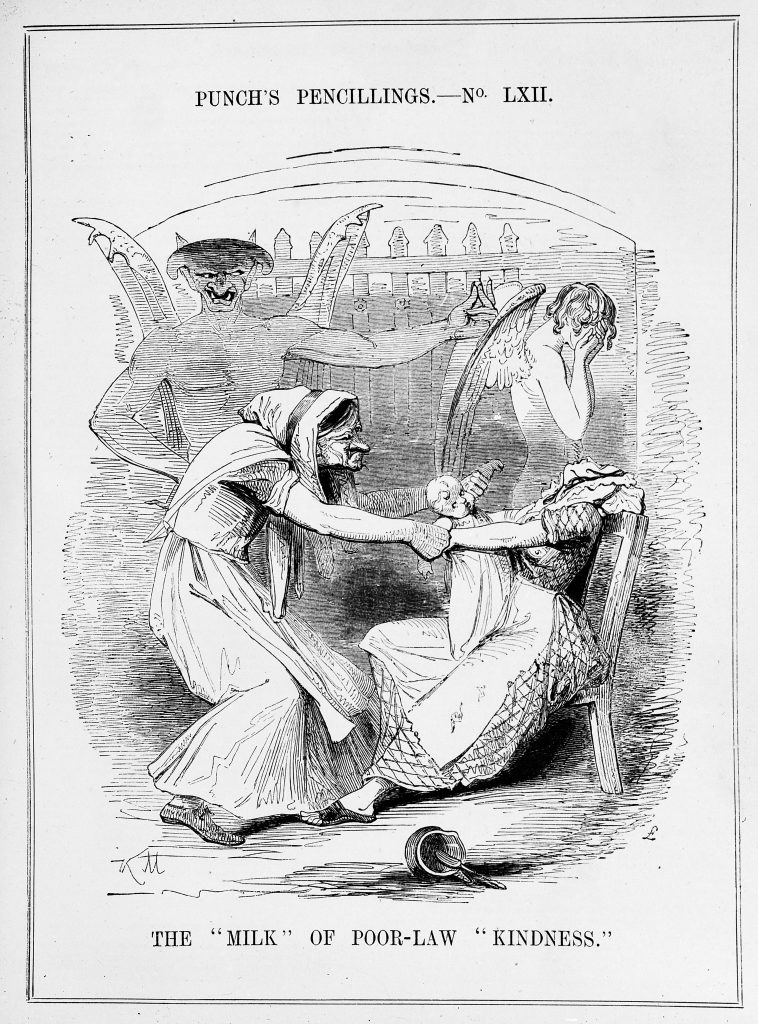

Image credit: The “milk” of poor-law “kindness”. Punch 1843. Wikimedia Commons.