Pessoptimism, noun, the inextricably intertwined feelings of hope and despair, of desire and knowledge, under the current untenable political conditions

Stephen Wright describes aptly the state of refugee justice in Australia today as a symptom of much broader malaise:

‘The existence of the detention centre on Nauru is a critical marker of the failure of our ability to maintain a commons, and of the failure of the Left’s imagination. The self-immolations of Hodar Yasin and Omid Masoumali are not just the suffering of offshore detention made visible. They are our commons burning.’ ((Stephen Wright, ‘On Setting Yourself on Fire’, Overland, Summer 2016, winner of the Overland/NUW Fair Australia Prize.))

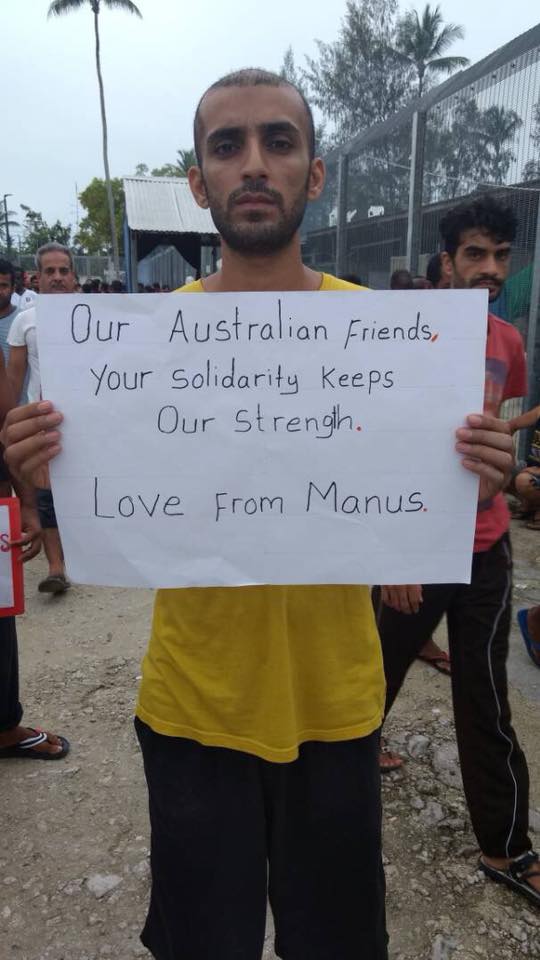

As I write, about 600 men in the Manus Island Regional Processing Centre are fighting for bare survival, in a situation invariably described as a ‘humanitarian emergency’ by the United Nations, and as the landscape of abject horror by the besieged refugees and advocates. The centre’s closure was followed by cuts to food, water, and electricity, even though the men remain on the grounds, refusing to leave for the much less safe ‘transit’ premises in the town of East Lorengau. The situation is indeed nothing short of a siege, as the Australian Navy stops each attempt to deliver the food and water to the men, despite the assistance received by some Manusians. The men are not convinced they are protected against attacks by local population, impoverished and hostile to the repeated colonial stakes exerted by the Australian state. Attacks against men have been a daily occurrence on Manus for years.

But what goes on now on Manus is unprecedented and almost inconceivable in its callousness, deliberate in its intention to brutalise the men in order to force them to leave the centre premises. There appears to be no accountability on the part of the Australian government to the United Nations, nor is there any support forthcoming from the UNHCR, or any of the countries deemed safe third options, bar New Zealand. Across the Tasman Sea, the newly elected Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has continued her predecessor’s offer to accept 150 refugees from the offshore camps, calls which have fallen largely on deaf ears. Short of a miracle, a humanitarian catastrophe is almost a certainty within days.

what goes on now on Manus is unprecedented and almost inconceivable in its callousness, deliberate in its intention to brutalise the men in order to force them to leave the centre premises

On the back of a fragile agreement between the Australian Government and the previous US Administration – an agreement that the current US President Donald Trump named the ‘worst deal ever’ – the US has taken 50 refugees from the camps on Nauru and Manus in an unconfirmed exchange for Australia’s acceptance of Latin American refugees. This is fewer than 5% of the total number of refugees that was initially mentioned when the agreement became known. No one knows if the US officials will return to either Manus or Nauru; it seems unlikely as the US President’s own focus shifts to the building of the Mexico Wall, and attempts to restrict immigration. The men on Manus have all but stop believing that the US deal will happen. But they are determined to fight; they maintain their own pessoptimism.

The Global Crisis ((Jenna M. Loyd, Matt Michelson & Andrew Burridge, Beyond Walls and Cages: Prisons, Borders, and Global Crisis, University of Georgia Press, 2012, pp.1-19.))

We are in the midst of a global crisis of nation-state citizenship and national sovereignty, evidenced by the state’s increased reliance on policing and reification of borders. The state’s response is equally a response to the globalised economy as it is a response to the histories of struggles for freedom from colonialism and oppression. This crisis eventuates at the historical conjuncture of several factors: the late capitalism (or what is usually known as ‘neoliberalism’) where wealth accumulation is the primary objective of the economic order; the climate crisis, brought on by human-caused global warming of devastating proportions; and the rise of white nationalism and the far right, most notably in the west and throughout Eastern Europe.

So ‘border protection’ becomes a defining moment for the west; Australia is now a world leader in the logistics and strategy behind the obsession with militarised border controls that have developed as millions of refugees fleeing the conflicts in the Middle East and Africa, arrive at the doorsteps of Europe and the United States. But this is not a ‘refugee crisis’, only crisis of the state and imagined sovereign borders.

About 65 million people are displaced worldwide as a consequence of war, conflict, and persecution, not including those displaced internally in areas of conflict. The vast majority are still housed in surrounding countries, usually also the ones who have suffered through wars and impoverishment at some point, with the richest nations fleeing from their responsibilities underwritten by numerous international conventions to which they remain conspicuous signatories.

There are about 100,000 people in and out of migration detention in Malaysia, and around 20,000 in Indonesia, our closest neighbours and departing countries for many people arriving by boat. Neither is a signatory to the UN Refugee Convention; neither has the capacity nor the political will to accommodate the ever rising numbers of forced migrants from what they rightly see as the consequences of western foreign policy. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection is spending considerable amounts of money directly in origin countries, on campaigns persuading people through propaganda and advertising not to leave danger, or paying police forces to strengthen local ‘border management’ and prevent departures.

The detention infrastructure which supports the industrial complex is spread throughout our region, and has been funded by Australian Government contractors such as Decmil, who built the ‘transit centre’ in East Lorengau where lack of safety is of paramount concern for the Manus men. The misleadingly named International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and others, have partnered with the government in the creation and maintenance of this infrastructure, and granted lucrative contracts by Canberra. The financial interests of big capital do not stop there: the Australian-listed companies, or major investors in Australia such as Woodside and Chevron, are implementing massive moneymaking resource extraction projects in the very geographical regions, such as the Rakhine state in Myanmar, from which refugees are fleeing state persecution.

Australia is now a world leader in the logistics and strategy behind the obsession with militarised border controls that have developed as millions of refugees fleeing the conflicts in the Middle East and Africa

Under these circumstances, Australian government – just like the majority of the international community – is free to not just ignore the regimes in countries like Sri Lanka and Myanmar, but in its complicity actively support their murderous campaigns. The international legal code under the purview of the United Nations, has proved miserably ineffective in dealing with the crisis, whether in preventing the causes behind the flow of refugees, or in ameliorating the conditions in which they live. The large non-government organisations, such as Save the Children and the Salvation Army, had abandoned their engagement in the carceral black sites of Manus and Nauru, not just a little blemished from their involvement. Their advocacy came only after the disaster had struck, and has cost them support, staff and other resources. They too, are part of a system that has generated large profits from human rights abuses.

This global crisis, then, manifests itself in the breakage of the old political order, and the resultant vacuum now gaping where we once have imagined our commons to be. Costing tens of thousands of lives annually, the most immediate crisis is the sheer extent forced migration and displacement, with long-term consequences for our collective future.

Post-Operation Sovereign Borders

The Australian refugee policy, known as the Operation Sovereign Borders, rests on two main pillars: forced turn-backs of boats intercepted by the Australian Navy to countries of origin; and the removal of the right to permanent protection for people found to be refugees. The old policy of containment, the indefinite mandatory detention of remaining asylum-seekers on Nauru, Christmas Island and in onshore camps, is being superceded. With the majority of asylum-seekers now living in the community under the volatile temporary protection system re-introduced by the Abbott Government, the remaining camps are undergoing changes of their own. The real ‘border protection’ is taking place on the high seas.

The Australian refugee policy, known as the Operation Sovereign Borders, rests on two main pillars: forced turn-backs of boats intercepted by the Australian Navy to countries of origin; and the removal of the right to permanent protection for people found to be refugees. The old policy of containment, the indefinite mandatory detention of remaining asylum-seekers on Nauru, Christmas Island and in onshore camps, is being superceded. With the majority of asylum-seekers now living in the community under the volatile temporary protection system re-introduced by the Abbott Government, the remaining camps are undergoing changes of their own. The real ‘border protection’ is taking place on the high seas.

The policy has been enforced under the pretext no one has ever found convincing: as a policy of ‘deterrence’ to stop the boats and save lives at sea. But the boats never stopped. The number of boats entering the regional waters has not reduced, and by the government’s own admission, at least one boat per month continues to be intercepted by the Australian authorities.There have been, most likely, hundreds of deaths in migration detention or in transit in our region over just the last couple of years, directly as a result of these interceptions. The Operation Sovereign Borders policy landscape has also resulted in the direct repatriation and forced deportations, often constituting refoulement to danger of at least a thousand people, and an action deemed unlawful under international law.

The policy has been enforced under the pretext no one has ever found convincing: as a policy of ‘deterrence’ to stop the boats and save lives at sea. But the boats never stopped.

The Australian government’s appropriation of human rights discourses created a challenge of mounting a successful counter-argument to the either apathetic or outright hostile Australian electorate. The Operation Sovereign Borders is a rehashed Pacific Solution of the Howard years, upped by the Rudd and Gillard Labor Governments which reopened the camps on Manus and Nauru. The swathe of legislation introduced since 2012 have effectively shifted and repositioned Australia’s borders to make it impossible for boat arrivals to seek asylum and be resettled in Australia. ((For a summary of these measures, see Madeline Gleeson, Offshore: Behind the Wire on Manus and Nauru, NewSouth, 2016.))

At the current success rate, around 10,000 applicants for protection under the aegis of a Temporary Protection Visa or Safe Haven Enterprise Visa, as part of the overall ‘legacy caseload’ of about 30 000, are likely to be potentially subject to deportation under our migration policy in the coming years. For political reasons, successive Australian governments are likely to prefer continuous uncertainty for these people, and turn it into an opportunistic political moment at benefit of the ongoing state campaign against boat arrivals:

‘Invisible barriers are built-in mechanisms which overall project the impenetrability of a country but would also keep those unwanted from entering the system of that country. Their existence seems to objectify the person that’s not wanted as s/he is contained at the margins of society, either in large disused spaces or left out from systems that would allow them to live their lives fully.’

The new politics of containment is both internal and external. The containment of people in detention camps and migration zones excludes boat arrivals to Australia from ever being able to settle and granted permanent protection. They are expected to queue in the order of all humanitarian entrants making their way under the UNHCR sponsorship. The reality is that we are facing a much larger nemesis to free movement of people than we have had to deal with thus far. Australian government’s pursuit of the doctrine of aqua nullius demands that the refugee justice movement meet more contemporary challenges.

Challenging the policy of containment

The following represents recommendations for essential elements of a successful refugee justice campaign:

Campaigns must be led by people from refugee and detainee backgrounds: this has been a key demand of the groups like RISE from Melbourne. Former detainees, refugees and asylum-seekers living in Australia, have established communities which should speak with primary voice on how the refugee justice movement should respond. RISE is running a #sanctionAustralia campaign, which intervenes in major international events to draw attention to refugee resistance in Australia and abroad. A successful disruption of the Melbourne Cup 2017 by the activists from the Whistleblowers, Activists and Citizens’ Alliance and RISE produced a social media storm on the day.

Campaigns must be led by people from refugee and detainee backgrounds: this has been a key demand of the groups like RISE from Melbourne. Former detainees, refugees and asylum-seekers living in Australia, have established communities which should speak with primary voice on how the refugee justice movement should respond. RISE is running a #sanctionAustralia campaign, which intervenes in major international events to draw attention to refugee resistance in Australia and abroad. A successful disruption of the Melbourne Cup 2017 by the activists from the Whistleblowers, Activists and Citizens’ Alliance and RISE produced a social media storm on the day.

We – the Left in Australia – need to revisit the global language of the commons – not as a concept that reproduces the colonial demarcations drawn out in the context of colonial dispossession – but the commons as a space where we make connections between the global challenges, where we speak of climate change in the same critical framework that recognises the inevitability of the collapse of capitalism. In practical terms, this means abandoning electoral solutions as effective, as pessoptimistic, because they have failed to provide even the short-term band-aids to the crisis of state Australia faces in its refugee policy post-Operation Sovereign Borders. Tactics such as boycott, disruption, divestment and sanctions, need to be given much larger space in the campaigning for refugee justice. These have achieved considerable successes in involving union members, workers, artists, health workers, and students in the refugee justice movement, and this momentum should be maintained. Protests alone, while important, need to be seen as displays of solidarity, not an end in itself.

Tactics such as boycott, disruption, divestment and sanctions, need to be given much larger space in the campaigning for refugee justice.

Solidarity with the First Peoples’ struggles is not negotiable: ‘to speak of opening borders without addressing Indigenous land loss and ongoing struggles to reclaim territories is to divide communities that are already marginalised from one another.’ ((Amar Bhatia, ‘We are all here to stay? Indigeneity, Migration and ‘decolonizing the treaty right to be here’, Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice, 31, 2013.)) Deep interconnections between the fight for land rights sovereignty and ‘border protection’, specific to settler colonies like Australia, are recognised by RISE, who see mutual value in the decolonisation process currently taking place across the progressive social movements.

With the loss of sovereignty and trust in government once held by the people, and replaced by the multinational capitalism, only a broader anti-racist, anti-capitalist action which campaigns on all causes of the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ can meet the challenges of restoring refugee justice globally and locally.