When discussing the topic of a Basic Income, the cost of the program is often people’s first question. After all, if the program were to deliver “an unconditional livable wage to every permanent resident” when the Henderson poverty line is ~$24,000/year and the population of Australia is ~24,600,000, back of the envelope calculations cost a Basic Income at approximately $590,000,000,000/year! Where would you even get that kind of money?

The question of whether or not it is rational, ethical or politically feasible to transfer this wealth is one that has been discussed at length elsewhere. The intent of this article is to instead break down why these back of the envelope costs are wildly misleading, suggest an alternative way to think about the costs of a Basic Income, and to offer some specific, practical suggestions for where to get that kind of money.

1. What do we even mean by “cost”?

Money serves several functions, but one of its core purposes is to represent the value of resources. However since the “true” value of resources can’t be known, all it can actually do is estimate the perceived value. If for some reason we were to perceive the resources (or the money itself) to have less value, then in economic terms they do have less value. This is part of the reason the 1990s tech bubble and the 2008 financial crisis were as shocking as they were. Suddenly the tech companies and mortgage backed securities that were perceived to have a certain value were then perceived to no longer have that value, despite the fact that the underlying resources hadn’t actually changed.

It’s important to underline the disconnection between the way the money measures the value of resources and the underlying resources themselves. The price of a bag of rice can fluctuate wildly from week to week as supermarkets change their weekly specials, but the physical nutrition gained from eating the rice remains approximately constant. Likewise, the price of a house can change wildly over the years, but the physical and psychological benefits of a safe enclosed space remain approximately constant.

[graphic interactivity is best experienced using a mouse]

Another way that money is confusing to think about is the way we relate to it on a national scale. As individuals, we get so used to experiencing money from our own perspective that thinking about it on a national scale can be counter-intuitive.

Take the following scenario in which you go out for dinner with a friend and then pay for dinner. The food costs money and therefore once the transaction is complete you no longer have that money. This seems fairly obvious so why waste your time with this thought experiment?

Instead imagine you’re watching the country from above and it’s your responsibility to keep track of where all the money is in Australia. From this perspective when one person buys dinner for their friend, the money simply exchanges hands with the restaurant owner. Shortly after, that same money is exchanged for piano tutoring. The piano tutor then exchanges that same money to pay an electricity bill.

This shift in perspective shows us that at every step of the way money gets “spent” but it never actually disappears in the way that it did from the individual’s perspective. Nobody is burning up the spent money, it just keeps circulating through the economy in one way or another. The idea that the money isn’t destroyed may seem obvious, but it runs counter to the way we talk about government spending. So what does this mean? Can the government spend money infinitely without repercussions?

To take this thought further, let’s imagine a simplified version of a Basic Income. In this simplified version, there are two people in the country; person A who works at the supermarket and person B who owns a supermarket. In the process of taxation, person B who owns the supermarket ends up being a net contributor to the Basic Income and is taxed $100, while person A who works at the supermarket ends up being a net recipient and receives $100 (more on net contributors, net recipients and taxation methods to come later in the article). Person A needs to buy food and so takes their newly gained $100 and spends all of it on groceries at the supermarket.

Let’s take stock of what happened in this exchange. At the beginning of the day, person B has the money and the groceries. At the end of the day, person B has all of the money they started with but they have $100 less in stock, which is now in the hands of person A. From this example it can be understood that the “cost” of a Basic Income should be interpreted in terms of resources rather than dollars.

Now of course there has been a lot omitted from my examples. How would things change when you have millions of actors rather than two? What about the difference between the cost price and retail price? These are good questions worth asking, however the intent of these examples is not to be a perfect simulation of an economy, but rather to highlight that it’s more meaningful to focus on the resources that are changing hands than the dollar amounts.

In a sense it can be thought of as if there are two parallel economies: a money economy and a resource economy. The money economy is easier to analyse, however ultimately what is most important is the resources that the money is intending to represent. The two economies are intended to align, however are not guaranteed to. This shift in perspective also makes the rice example more intuitive to interpret, because if the focus is on the resources the rice provides (nutrition) rather than the dollar price then the “cost” of the rice remains constant.

But don’t take my word for it, take the world of former Chief Economist on the US Senate Budget Committee, Steph Kelton:

(quote source).

Of course money is important and there is no avoiding it when funding a major policy like a Basic Income, but when the price of goods can change on a whim, worrying about the exact dollar cost is a fruitless exercise. We must take a step back, look at the bigger picture and remember that at the end of the day money is a stand-in for the actual resources. Instead of asking whether we have enough money to pay for a Basic Income we should instead ask whether we have enough resources to go towards what a Basic Income would pay for. It’s the resource cost, not the dollar cost we need to be focusing on.

So then the question is, do we have the resources (housing, food, electricity, etc) to meet the needs of every permanent Australian resident? And to that the answer is, unambiguously, ‘yes’.

2. We live in one of the most abundant societies in history

If the cost of a Basic Income should be thought about in terms of the resource cost rather than the dollar cost, how does Australia stand in terms of resources?

We can look at specific examples such as Australia having more empty homes than homeless people (x) or the production capacity to produce three times more food than is required to feed our population (x). However, by looking at specific industry examples we aren’t able to fully explain the big-picture and unfortunately most of the statistics that tell the story of the big-picture are provided in terms of dollars.

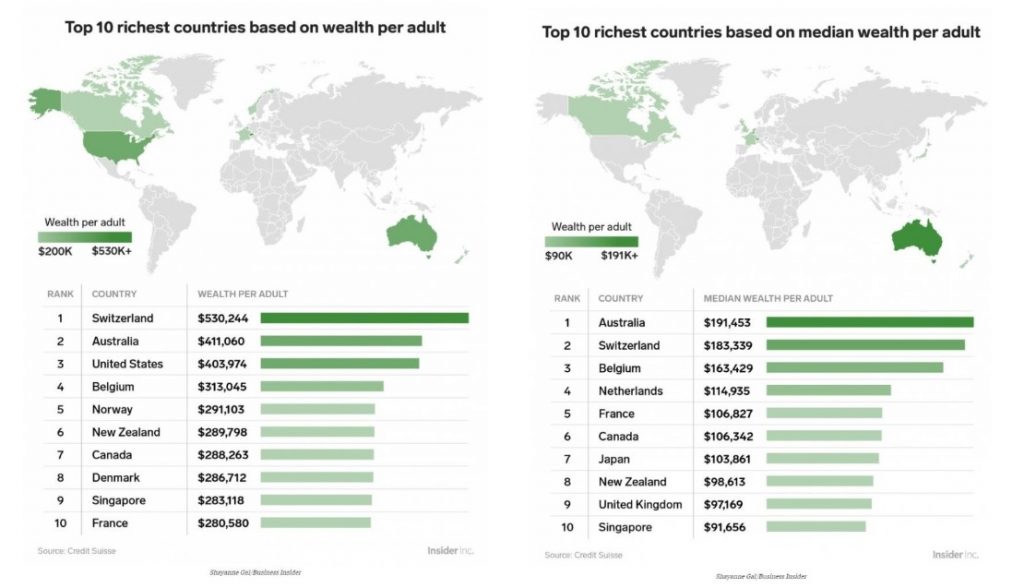

The good news is that by looking at the dollar amount it is clear that (in relative terms) Australia is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Depending on which metric is used, Australia either has the highest median wealth per capita ($191,453 USD), or the second highest average wealth per capita ($441,060 USD) (x). We’re loaded!

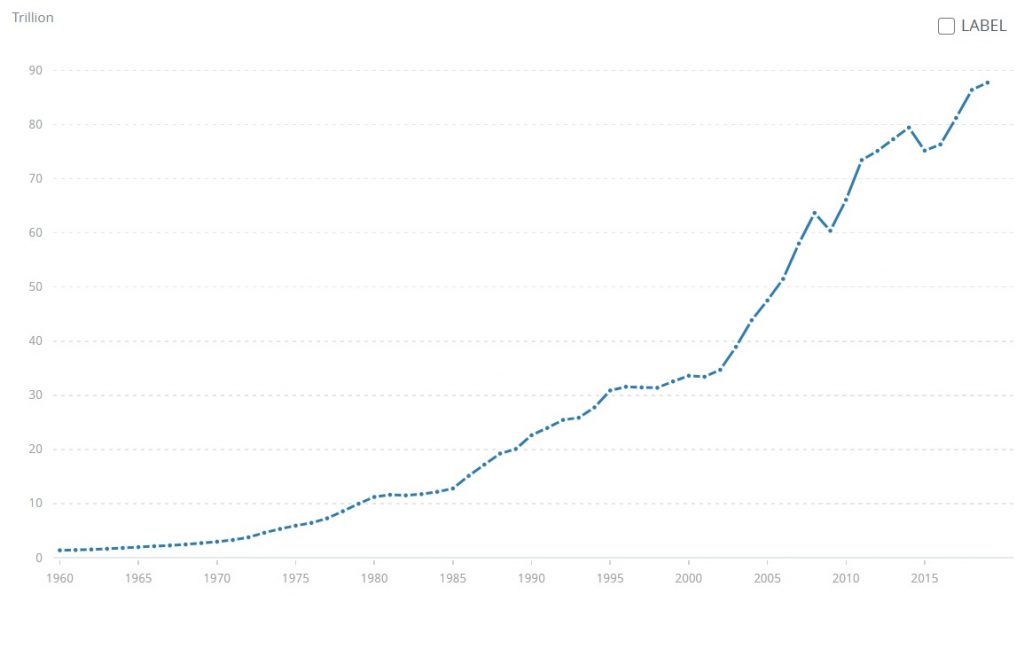

GDP is a terrible metric to use in absolute terms (x), however this graph (x) of global GDP spanning approximately 80 years shows an undeniable upwards trend. In relative terms this indicates that we not only live in one of the most wealthy societies alive today, but also one of the wealthiest in history.

If the idea that Australia is a wealthy country is hard to reconcile with your lived day-to-day experience, that may be because Australia’s wealth is increasingly unevenly divided. The poorest 40% of households hold ”just 2.8 per cent of the nation’s wealth between them” (x) and the “number of Australians living below poverty line has not declined since 1980s” (x).

By looking at how wealthy Australia is overall this makes clear that even if we happened to not have enough resources to provide the necessities for everyone (which we do), we have enough production in “non-necessary” fields that give us a lot of slack. A country only needs so many clowns, pet costumes and corporate lawyers and we could always redirect the energy currently being put towards those markets towards more critical industries if required.

Given our relative wealth this clearly isn’t something we’re faced with any time soon, but I find it a revealing fact to be reminded of. Any time someone goes without electricity or water, it’s not because we are unable to generate electricity and sanitise water, it’s because as a country we have decided to prioritise other things above meeting everyone’s needs.

The problem isn’t that we live in a time of scarcity, the problem is that the wealth of our society is poorly distributed.

3. You can design it however you like

Defining a Basic Income as an “unconditional liveable wage for all” makes it clear that it is an outcome rather than a specific implementation. Let’s walk through the design process of a specific implementation together so that we can think about the pros and cons of choices along the way. To begin with, let’s start with an understanding of what the resource/wealth distribution of Australia looks like currently, since that is the primary thing the Basic Income is focused on changing.

[graphic interactivity is best experienced using a mouse]

[this graph is based on household wealth data (found here) rather than individual wealth data that couldn’t be found. That data was then manipulated so that it is categorised by percentile. The top 1% was then adjusted so that it more appropriately matched this more recent analysis. The data has also been smoothed to make it more visually appealing. This is not intended to be a perfect model, rather to help people get an intuitive visual understanding of the modelling. The poverty line at $60,848 per household is based on the Henderson Poverty Line and average household size.]

This graph represents household data and is organised by percentiles in a way such that the average wealth of families in the poorest 1% of people in Australia (approximately 250,000 people) is represented by the height of point on the very left and the average wealth of the wealthiest 1% of households is represented by the height of the point on the very right. The first thing worth noticing is how extreme this graph is, household wealth at $60,000 and at $0 appears to be at the same point. Try using the scaling slider on the image to adjust the scale of the graph.

The most important part of a Basic Income –and what many advocates would consider its defining trait– is the “floor”. This is the amount of wealth that all people in the society will have –as a minimum– after receiving the Basic Income. This is derived from one of the central claims Basic Income advocates make, which is that the rate provided should be high enough to allow everyone to meet their basic needs without a job.

Thinking about basic needs, food, water, electricity, housing are obvious, but is a morning coffee every day a need? A mobile phone? There is no single answer to these questions because each person is going to feel differently about it and it’s also subject to changing over time. Around 30 years ago when the internet first became available to the public it would have been hard to make the case that it was a necessity for all, but in recent years (and most notably since the Covid-19 pandemic) it’s hard to make the case that it isn’t. (x)

The rate of the floor could be fixed to the poverty line or an economist endorsed cost of living, however that still leaves a lot of room open for interpretation and debate since there are many different poverty lines. (x) (x) (x)

GetUp’s Future To Fight For campaign included a Guaranteed Basic Income that would provide a variable rate depending on the recipient’s living conditions (x). This would have meant that a single woman and a single mother would receive different rates because they have different expenses.

In the 2019 election the Labor party and broad union movement advocated for raising the minimum wage to a “living wage” of about $37,398/year (x) which indicated that there is some political consensus Australia has enough wealth to be distributed to all at that rate. A year later at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, the United Workers Union called for a $740 per week income guarantee welfare payment.

The ‘wealth per adult’ statistics quoted above in section 2 (x) imply that if every citizen were to have equal wealth then we would all have $951,413 worth of resources each and therefore theoretically that is the current limit.

When considering how the rate of the floor changes over time (or doesn’t, as is the case with Jobseeker payments (x)), one common proposal is to link it to a figure such as GDP so that as the production of the country increases, as does the proportion of wealth distributed to each resident. A gesture that would encourage camaraderie throughout the country as our collective prosperity is shared. Alternatively, some advocates suggest (x) that the rate should be incrementally adjusted until it reaches the highest level possible that doesn’t cause inflation, with the objective to maximise the flow of money throughout the economy.

Use the second slider to see what the wealth distribution would look like if every citizen was to be given an equal amount of additional wealth.

[graphic interactivity is best experienced using a mouse]

The big problem is that this graph doesn’t represent the money each person has, it represents the wealth each person has. Therefore this current model breaks the laws of physics and creates wealth out of nothing. The wealth obviously needs to come from those that have it, but how much and from who specifically?

Like the floor, the “gradation rate” can be designed in many different ways. If you need a hypothetical $100 you could take $100 from one person, or $10 from 10 people. Do you distribute the costs evenly and have everyone chip in a bit? Or do you focus on the ultra wealthy in order to expand the middle class? Or how about something in between with everyone paying a small amount but the wealthy paying a bit more? For now this model assumes the Basic Income would be funded via a wealth tax, but other methods of thinking about funding will be discussed later in this article.

Despite the fact that there are an infinite number of ways to structure the gradation rate, the one method that mathematically wouldn’t make any sense at all would be to tax the poor to give resources back to themselves. If we’re talking about resources and wealth that has to come from somewhere. If they don’t have it to begin with, they’re not going to have it to give.

When people first hear that a Basic Income is given to all permanent residents unconditionally –including the wealthy– they often assume that it’s not a targeted program, and even sometimes malign it as a “handout to millionaires” (x). What this analysis omits is that by definition all forms of a Basic Income transfer wealth from those who have it to those who don’t. Mathematically, all forms of Basic Income must be redistributive.

Here’s a new version of a graph that show what the wealth distribution would looks like if taxation was included.

[graphic interactivity is best experienced using a mouse]

This current design is providing the essentials to all and isn’t breaking the laws of physics — Fantastic! We’re making progress! But it has one big problem: it has created a poverty trap. People who are working a small amount will end up with the same amount in-pocket as those who didn’t work at all. This is visualised by the flat section on the left where the original graph showed a slope. For some people this may be the ideal system design, but I personally think it would create undesirable incentives. Let’s make one more change and have the lower end of the graph taper to the original curve, representing the rate of Basic Income being additional to what people at that level are being paid.

Here’s a new version of the graph that includes tapering to remove the poverty trap.

[graphic interactivity is best experienced using a mouse]

It’s worth noting at this point that not everybody is ending up with more wealth than they began with. I refer to this as the “flex point” and people below it end up being net Basic Income recipients, while people above this level end up being net Basic Income contributors. I think the flex point is a critical factor in any Basic Income design as it indicates which demographics the designer feels neutral about. Is someone with $30,000 of wealth who they consider to be in the middle of the economy? $80,000? Or the statistical average of $951,413? (x)

Play around with the final slider to adjust where the flex point lies.

[graphic interactivity is best experienced using a mouse]

It’s a simplistic model, but we’ve got something workable!

Let’s take stock of what has been covered in this design so far: the core variables are the “floor” (the level we define to be a livable wage), the “flex point” (the point(s) at which the contribution to the Basic Income perfectly balances with the amount received) and the “gradation rate” (how steeply the wealth changes around the flex point).

4. Comparing policies

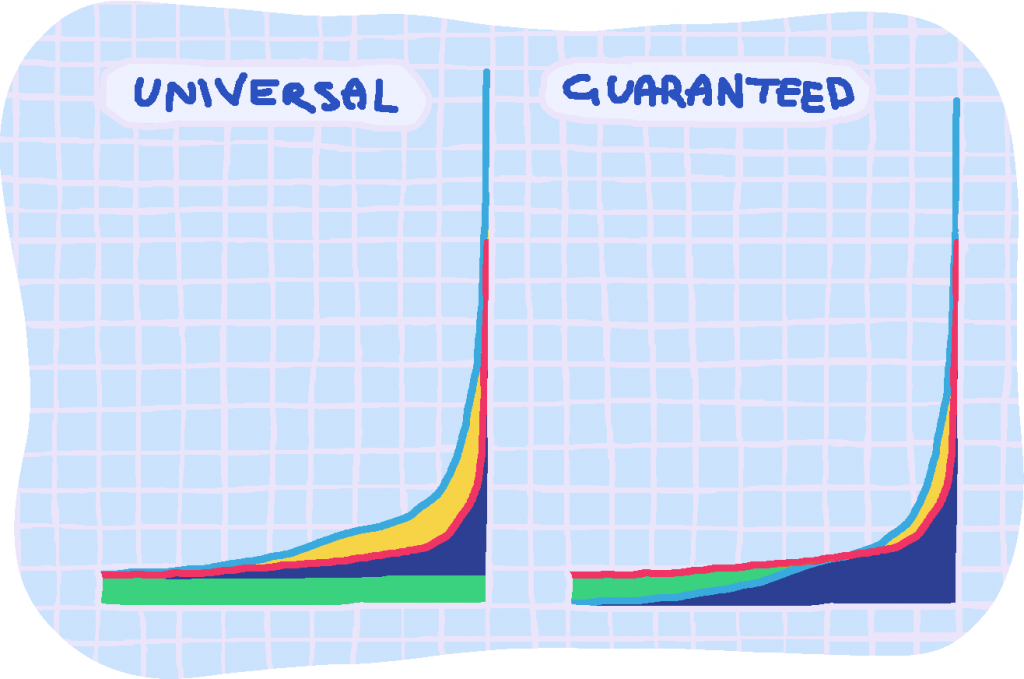

With all of this in mind, let’s take another look at the Guaranteed Basic Income (as compared to the Universal Basic Income that is more commonly discussed) proposed in the GetUp Future To Fight For Platform. Their distinction of what made it Guaranteed rather than Universal was that anyone above the flex point (who would be a net contributor in the Universal equivalent) wouldn’t receive any money at all. This in turn meant that those same people above the flex point would be taxed less and ultimately that everyone at every point along the wealth distribution would end up with approximately the same wealth in either model.

The core of their logic was that it would cost less and therefore be more politically feasible. But if both policies can achieve approximately the same wealth distribution, how can that be? The answer lies in whether we’re talking about the net cost or the gross cost. The gross cost is the total amount taxed. The net cost is the total amount taxed minus any Basic Income payment that contributors receive back.

Which of these two metrics to use then becomes entirely a political question. Do you mean the number written on the balance book or do you mean the transfer amount that indicates the impact on society? Is it meaningful to say that a person was taxed $100 if they also gained $100 in the process? And do you have a political incentive to make the Basic Income look wildly more expensive than it practically would be?

[note that this image has been exaggerated in order to make the different segments more visible

green area: welfare payments made,

yellow area: taxed wealth,

red line: net result that is theoretically equivalent in both cases,

navy area: untouched wealth,

blue line: wealth distribution after welfare and before taxation]

Some advocates of the Guaranteed version say that the Universal version would result in “tax churn”. This is an unusual critique that suggests that it’s inefficient to tax someone and then use that money to fund services for that person, due to additional bureaucracy being required. “Tax churn” doesn’t appear to be a standard phrase for economists to use and seems to originate (x) (x) from The Center Of Independent Studies (x), an Australian right-wing Libertarian Think Tank with an explicit motive to decrease the amount of money flowing through the government (x). The critique is particularly suspicious given that it’s hard to make the case that a means-tested welfare program would require less administration than a universal one that doesn’t require means-testing administration.

Another version of the Basic Income that can achieve approximately the same outcome is often called a “Negative Income Tax”. Typically it’s structured in a way such that people below the flex point would receive a payment from the government at tax time, rather than a tax bill to pay. The amount they receive would be a function of their income so structurally it would achieve approximately the same wealth distribution as the Universal and Guaranteed alternatives, but would operate more like the Guaranteed version as nobody contributing to the program would receive anything in return.

One problem with the Negative Income Tax is that if it’s paid out annually it won’t be particularly useful for people experiencing poverty to wait several months for their lump sum payment at the end of the financial year. Alternatively, if it operates similar to a PAYG model and it’s not paid out annually, then all of the efficiencies in administration (that come from the tax department coordinating people’s incoming and outgoing finances all at once) become redundant and what it’s left with is a makeshift version of the Guaranteed Basic Income with the tax department substituted into the role of the welfare department. Another problem with the Negative Income Tax is that the emphasis it puts onto income taxes implies that income taxes are either the only form of taxation or the most desirable form of taxation, neither of which is correct.

Another policy that achieves similar goals to a Basic Income is called Universal Basic Services and would provide the resources people need directly rather than the money that could be in turn used to purchase the resources they need. This doesn’t appear to have the level of supporting research or political enthusiasm that it’s cash transfer equivalents have, which is likely because it would be many orders of magnitude more complex to implement. In order to provide the services, each individual service would need its own policy prescription (x), whereas the cash transfer equivalents can leverage existing systems to achieve an approximately similar outcome. Another notable disadvantage of providing services is that some essential services don’t lend themselves to a standardised “one size fits all” model of delivery (x).

5. Getting money to people

So far this article has discussed how the real cost of a Basic Income is a resource cost, how Australia is abundant with resources and how there are many possible ways of structuring the distribution of wealth of the country — a Basic Income is possible in Australia! This section will discuss some of the methods through which a Basic Income could be implemented.

It’s worth noting that as this section focuses on money rather than resources it becomes less intuitive as there is not a direct 1-to-1 relationship between resources and dollars. Some methods may appear as if they are economic sleight of hand and that is because they are and money is a social construct. The methods of money transfer are worth acknowledging, however we should remember that we live in a physical world and the human-created abstraction of money should be considered secondarily to the actual physical resources it is intending to represent.

With that in mind, if in order to transfer resources to people there needs to be an initial transfer of money (as demonstrated in the supermarket example in section 1), where should this money come from? Three sources will be discussed: transferring existing money through taxation, creating new money and investment dividends. It is of course possible to have a combination of these methods being used in conjunction and I personally think that a diversified approach is likely to be the most effective to implement.

5.1 Taxes

Taxation serves the purpose of redistributing wealth and it additionally contains a “carrot and stick” feature that can be used to curate the economic incentives and disincentives within our society. An alcohol tax (x), for example, would make it more expensive to buy alcohol than non-alcoholic equivalents, thereby disincentivising the purchase of alcoholic products. If taxation can be used to serve the purpose of curating social incentives, the question of what to tax then becomes a social question of which aspects of our society to disincentivise, more so than an economic question.

Pollution taxes (such as carbon taxes (x)) are an example of a “disincentive tax” because there has been a scientific and social consensus that carbon emissions are detrimental to society and by taxing it, the social cost can be translated into an economic one. Financial transaction taxes (x) are another example that could be implemented in order to disincentivise the high frequency stock trading that makes stock markets more volatile (x).

Fines can be considered a one-off disincentive tax and if the revenue was distributed to all then it could be seen as a compensatory dividend, albeit a small one.

One aspect to be wary of regarding disincentive taxation is that if it’s being used to both fund the Basic Income and also disincentivise something we don’t want, that then creates a perverse political incentive to keep the thing we don’t want around in society. For example, if a Basic Income was funded through some kind of smoking tax, then there would be an incentive to sustain the smoking industry in order to keep the Basic Income funded.

The great irony in the logic of disincentive taxation is that the most common forms of taxation people encounter today are applied to activities that it’s generally agreed we want people doing, but that people have little-to-no ability to opt out of: income taxes and sales taxes. One feature of income taxes worth noting is that someone who has a wealth of $10,000,000,000 but no income (or an income through a non-work source) wouldn’t be affected by it at all. Whether or not this is desirable depends entirely on how you would prefer wealth to be distributed throughout society.

Personally I think the idea of inescapable taxes is a good strategy, although I think that by prioritising income and sales taxes we target the wrong people and activities. My personal approach to taxes is to think of them as variations on a “footprint tax”. That is, anyone who takes up a larger than average portion of Australia’s resources should be taxed to compensate those who have less. The motive behind this would be to disincentivise hoarding, effectively to say “you can use more resources than everyone else, but you have to pay for that privilege”.

A progressive land tax is an ideal example of the footprint tax philosophy. It would involve taking the total amount of privately owned land and dividing it by the number of citizens in order to get the average amount of private land per person if the country was split equally between every citizen. Anyone who owns more than that amount of land would pay a tax to compensate for that additional ownership. This shouldn’t be confused with a land value tax (x) which seeks to tax the increase in the value of land, so that an unused block of land in a growing neighbourhood wouldn’t return a dividend to its owner as the value of the land increases.

The same footprint tax philosophy could be applied to other natural resources, such as using a more than average amount of water, extracting more than an average amount of natural minerals, using a more than average fraction of mobile broadcasting bandwidths and storing more than an average amount of data (a resource that has recently (x) been described as being more valuable than oil). Wealth taxes are a method of applying a footprint tax to all resources simultaneously and it’s for this reason (along with the simplicity of modelling) I treat it as the default tax.

To re-imagine the graphs in section 3 with this more complex analysis of taxes, we could visualise them as a 3d plot. In this case, a meat tax (x) and a wealth tax implemented together could be visualised with one axis referring to wealth and another representing meat consumption. In the previous graphs each person was represented with a position along the horizontal axis of the 2d graph, but now the wealth of each person is represented with the height of one point on the 3d graph depending on how much wealth they had originally and how much meat they consume.

In this case the wealthiest would be taxed more, but there would be an additional dimension as people who have the same amount of wealth but eat a different amount of meat would end up with different amounts of wealth. This gets much harder to visualise as more kinds of taxes are implemented (and more dimensions are added to the plot) but hopefully this interpretation makes it clearer how different combinations of taxes can produce more nuanced models than the ones shown in section 3.

The final point about taxes that needs to be addressed is how high they would have to be to fund a Basic Income. Given that a Basic Income is an outcome rather than a process, the rates that would be needed are the rates that would achieve the socially desirable transfer of wealth. Since this isn’t a fixed rate, likewise the amount of taxes needed also isn’t fixed.

Additionally, it’s worth noting there needs to be a critical mass of wealth flowing through whatever is being taxed. A Basic Income funded exclusively via a speeding ticket fines or another small, targeted tax would redistribute wealth from speedy drivers to everyone else, (and could even be designed in a progressive way as they do in Finland (x) where the speeding ticket is linked to the amount of wealth you have) however it’s unlikely to have enough revenue for a Basic Income. From a resource perspective, this inability comes from the fact that the speeding fines are not likely to be equal in value to the wealth transfer required to provide an unconditional liveable wage to all.

5.2 Creating money

Every dollar circulating through the economy today had to be created at some point, either by the government or by banks in the form of loans (x). In an effort to decentralise the power of these two organisations, some people suggest that new money should instead be given directly to the residents of Australia in the form of a Basic Income (x).

Prior to the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, a Basic Income funded even in part out of newly created money would have been broadly rejected given that an increased money supply without a guaranteed equivalent increase in resources was assumed to lead to a devaluation of the currency (x) (x). However during the time of lockdown when many people were unable to work, the money supply was increased by upwards of $500,000,000,000 (x) and there was no significant impact in overall inflation (x), despite some inflation of select goods (x). This is not to suggest that money can be created infinitely without repercussions. Advocates for this method of funding often propose that there is an ideal amount of money to have in circulation and that currently we are below that amount (x).

Advocates for a Job Guarantee driven by Modern Monetary Theory make a compelling case (x) that under-utilised economic potential could be activated by adding cash into the economy. Someone sitting at home without any money could be producing more value if they had more resources to work with. This logic applies equally to the funding of a Basic Income using the same methods, given that every task that could be done with a Job Guarantee could be done with a Basic Income (x).

Looking outside of the government, some people propose that new local currencies (x) should be created with unconditional cash transfers built into their foundations. Quite often this is proposed as a cryptocurrency (x), however many of the same principles apply to non-digital currencies. Unlike the Australian dollar, these local currencies are limited in their legitimacy, however they can empower communities with the flexibility to design the currency to their needs. For example a base amount of the money could be created and periodically given to each registered user unconditionally and in addition money could be created and given to people who provide evidence of performing socially useful tasks that aren’t acknowledged by the formal economy such as planting trees.

While I do prefer the idea of money creation in the form of direct cash transfers rather than bank loans, I am generally not fond of these methods of funding a Basic Income. I think that for a long time we’ve been told a story that the wealthiest will always be able to avoid taxation and out of defeatism many people have looked for alternatives that leave the wealthiest untouched. When I look at graphs such as the original wealth distribution graph shown in section 2 I think that lack of distribution is one of our biggest problems and that that is a problem worth tackling head-on.

5.3 Investment dividends

Investment dividends would involve the government using either of the previous methods to purchase an asset that would ultimately pay for itself, and thereafter provide a revenue stream for a Basic Income. This process of purchasing assets with a return on investment is a typical one and it’s why the government makes distinctions between “good debt and bad debt” (x), although there seems to be some political fear around utilising this strategy more actively.

Education is a traditional example of an investment that pays for itself, with some estimates calculating the return on investment at around $7 for every $1 invested in higher education (x). If we were to invest in making university free, we would redirect resources from other areas of the economy with the expectation that the educated people would compensate by later generating more value than they would have without that education.

One common method of using investments to fund a Basic Income is through a Social Wealth Fund (x). The way a Social Wealth Fund works is that a state-owned investment fund purchases stocks, bonds, real estate and other assets and the dividends from those assets are distributed directly to the Basic Income recipients. Arguably the most successful Partial Basic Income in the world today (and for the last 44 years) is the Alaska Permanent Fund (x) which provides a dividend of approximately $1000-$2000 each year to each permanent resident of Alaska.

A form of investment that seems particularly appealing to me is to invest in autonomous infrastructure because if machines are able keep society functioning then people can spend their lives doing things that are more meaningful to themselves. Some estimates predict that the additional wealth in Australia due to automation over the next five years is “between AU $140 billion and AU $250 billion” (x) even without a proactive government strategy to invest in it.

I’m a robotics engineer and every day I see dozens of examples of tasks that are redundant for humans to be doing given modern levels of technology. Retail jobs are highly repetitive and therefore ideal for automation and currently employ approximately 1,285,000 people (x). Amazon Go is leading the way in developing autonomous stores in the US (x) and Coles is currently signalling an intention to move their stores in the same direction (x), but what if the government were to take a proactive role to invest in this kind of technology? Rather than private companies holding the patents, the technology generated could be freely accessible in a similar way to previous government inventions such as the internet.

Another return on investment not often considered comes from the implementation of the Basic Income itself. If a Basic Income is defined as an unconditional livable wage to every permanent resident of Australia it would result in the end of poverty by definition. Poverty is an expensive aspect of society and there is a good case to be made that if an entire society was “vaccinated” against poverty then there would be savings.

In the US, a total of about $32,000,000 was spent over a 10-year period in a global campaign to eradicate smallpox. It is estimated that that cost is saved every two months since 1971 in the forms of reduced administration costs, medical care and other costs (x), effectively paying for itself many times over. Australia understands that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, which is why we provide a certain level of healthcare to all citizens unconditionally. Given that poverty is linked with an increased need for child services (x), prisons (x) and policing (x) we should have the same approach towards poverty.

These preventative savings suggest that even the net cost of a Basic Income (the total amount taxed, minus any Basic Income that contributors receive back) makes the Basic Income appear more expensive than it actually would be (x). Some advocates even think that the return on investment from ending poverty would equal the resource transfer, leading to the program ultimately paying for itself (x). I personally find this a difficult case to make as it’s based on a hypothesis that can’t be proven unless the Basic Income were to be fully implemented, however I think it’s an important theory to consider.

The return on investment of implementing the Basic Income itself doesn’t just apply to people in abject poverty either. How many people have big ideas that could change the world but are trapped working a job they don’t personally think is meaningful? According to some statistics in the UK this figure is almost almost 40% (x). “If just one Einstein right now is working 60 hours a week in two jobs just to survive, instead of propelling the entire world forward with another General Theory of Relativity… that loss is truly incalculable” (x). This is not to mention the additional entrepreneurial opportunities people will have available to them as the additional cash circulates through their local economy. These kinds of cost and benefit analysis often get lost in an economy so focused on quarterly profit that it misses the potential for longer-term investments.

It’s also important to look at other kinds of value that it would generate beyond the economic value, because how can you measure the dollar value of someone engaging more with our democracy who wouldn’t have otherwise? What would be the dollar value of someone being a more engaged spouse, sibling or friend who is currently drained of time and energy? What price can be put on someone spending their life doing what they are personally most passionate about?

6. How much did it cost to free the slaves?

When the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863 it was an immense financial expense to the slave owners. Similar to wealth distribution today, the ownership of slaves was highly skewed with the poorest 80% of the population owning none at all and only 0.11% owning more than 100 slaves (x). There is also evidence that slavery was highly profitable for the owner, as the slaves tended to work harder than “free labor”.

Some predictions put the cost of the slave industry leading up to that moment as up to $13,000,000,000,000 in 2016 USD, which can be understood as roughly 77% of 2016 US GDP. When the South seceded, a single slave would cost as much as $150,000 in 2016 USD, which was twice the average of just 14 years earlier indicating an upward market trajectory. This financial cost undertaken with the stroke of a pen cannot be understated.

But does the financial cost matter? Or does the human benefit outweigh any financial cost regardless of how high it may be?

Our modern economic system is unquestionably less physically violent than slavery was, but if slavery was less physically violent and still maintained systems of ownership of other humans wouldn’t it have still been abhorrent? Today we don’t have legal outright ownership of humans, instead we have devised a human rental system that most people are forced to participate in to meet their needs. To be clear, that’s not to say that our current system is as bad as slavery, rather that the two systems share the same core injustice.

I’ve discussed the flow of resources a lot throughout this article, but the one resource that is perhaps the most precious often gets disregarded by politicians and economists: our time. For me, this is what links the institutions of slavery and jobs. We have such a precious, finite amount of time on this earth and it’s morally unjustifiable that we force everyone to work to meet their needs, particularly given the technologically unprecedented time we live in.

The financial cost of a specific implementation of a Basic Income can be calculated but it ultimately doesn’t matter. This is an ethical question first and an economic question second.

7. What do the economists think?

Given that economics is a social science and it is difficult to come to definitive conclusions in social contexts, the field is rife with disunity. I find that it’s possible for any political ideology to find an economist who agrees with it and it’s for this reason I don’t put much personal stake in what individual economists think, instead preferring for economics analysis to be driven by logical reasoning. It’s for this reason I think we need a new form of economic policy that is structured in a way that is intuitive to all kinds of people, opting for broad universal programs that are easy to understand rather than byzantine welfare labyrinths. This quote from Yanis Varoufakis sums up my belief fairly well:

“Most folks have become convinced that economics should be left to the economists because it’s difficult … but if we accept that then democracy is dead … If we believe that there is such a thing as an expert to whom we defer on all economic decisions then what’s the point of democracy? Lets just not have elections any more, let’s have the experts run the economy. Because the economy –in the world we live in– is everything” (x)

However with that said, it would be foolish to write an article about how to pay for a Basic Income without mentioning which economists have endorsed it, given that it has such high profile endorsements.

For a more comprehensive list of endorsements, the live Google Sheets document linked here is thoroughly sourced and well-maintained.

Conclusion

The question of how much a Basic Income costs is the wrong question to begin with. This isn’t an equation that can be simply plugged into a calculator to “solve for x”. Deeply embedded into this discussion are questions of what we value as a society and why.

The more meaningful questions we should instead be asking are what we define as a living wage, how we would like wealth to be distributed throughout society, and what methods of distribution are the most aligned with our values.

A Basic Income is a powerful idea that could redefine the way we think about work, welfare and leisure in the 21st century. We have the resources to do this, let’s not miss this opportunity by getting distracted by the numbers in a balance book.