This paper formed part of the Green Institute Report ‘Rebalancing Rights: Communities, Corporations and Nature’.

As an Australian, I am proud that my country was central to both the writing and the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. The head of the Australian delegation and later President of the UN General Assembly was Australia’s Dr H. V. Evatt, an unstoppable force who tirelessly negotiated the final document. We were proud of our human rights contributions during the 19th and early 20th centuries, but for the past 30 years the ‘liberalism’ of neoliberalism has not supported a rights agenda. Instead, ‘free market’ neoliberalism has decided our public policy and Australia’s democracy is weakened as a result.

Until recently, the tenets of neoliberalism – deregulation, smaller government, competition policy, privatisation, ‘trickle down’ economics and attacks on the advocacy role of civil society – have played out without being named as a coordinated theory. George Monbiot points out that if we were living under communism, it would have been named, but he argues that neoliberalism’s proponents deliberately chose not to promote it by name (Monbiot 2016). Today, neoliberalism is being called out and named. Its extremes have unmasked its favouring of big business over the wellbeing of all the community. Yet, power still resides in forces that are not sympathetic to the rights of the community as whole. The right to advocate and protest is at the core of our democracy, but Coalition (and too often Labor) governments continue to limit this right.

Why is the NGO Sector Important for Democracy?

Traditionally our system of representative government has the NGO sector playing a mediating role between the state and the individual. It is a flexible, variable and effective way for individuals to relate to the political system. Political rights, such as free speech in the Universal Declaration and in the various conventions and declarations that have flowed from it, are a necessary part of relating to the political system.

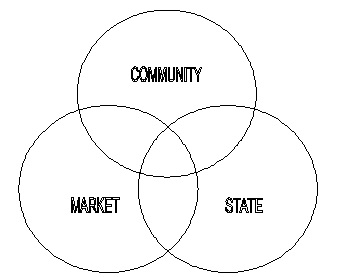

The following diagram is a model often used by social scientists to describe society and the relationship of its three democratic elements – government/state, corporations/market, and community/NGOs. Each sector is important in its own right, yet each depends on and complements the other. The diagram demonstrates the uniqueness of each sector, and that the boundaries between them sometimes merge. Importantly, each should play an equal part in the functioning of a modern democratic society.

Yet today the circles are no longer equal in size. The balance in our democracy is out of whack. The market/corporations circle is huge, while the government/state circle is smaller, and the community/NGO sector is greatly diminished. 30 years of neoliberalism have shrunk the size of both government and community and today we have a bloated ‘market’ sector where corporations call the tune for governments. The economic theory of neoliberalism has become an ideology, promoted by those who have found a way to profit from it. The neoliberal mantra of ‘smaller government’ has seen the public service shrunk and its services outsourced to the market. At the same time, the ‘deregulation’ or ‘cutting red tape’ mantra has seen corporations given free rein in situations where previously government oversight or regulatory bodies balanced the right of the public with the right of the corporation to make money.

We can identify seven positive contributions NGOs make in their unique role. Our public discourse should celebrate and value these contributions. They are:

- Proposing policy and commenting on policy is vital to good policy-making by both government and business. People on the ground can see and predict the result of policies more effectively and so make improved outcomes possible for all. The relationship need not be a confrontational one and earlier Australian governments, such the Hawke government, actually went out of their way to set up advisory committees of NGO representatives to glean good ideas and refine policy.

- Importantly, NGOs are uniquely placed to support policy that looks to long term goals, or policy that affects the future. Governments react to the short electoral cycle, asking ‘how will it affect our chance of re-election?’. Corporations have a legal responsibility to ask ‘how will it affect our bottom line’?. It is a special quality of the NGO sector that it has the flexibility to include the long-term in its policy interests and in its desired outcomes. What better issue than climate change to demonstrate this point?

- The sector also provides a check against the views of powerful, organised, economic interests. There is a large imbalance between the power of vested interests and that of the individual. A well-functioning society needs a balance between the power of government, economic interests and the community. There is inevitably a healthy tension between the three sectors, but keeping the balance of power between the sectors is the challenge faced by a democracy.

- NGOs have an accountability function. They inform the community about the behaviour of governments and businesses and call them to account. NGOs can claim legitimacy for this role if their roots are in the community and they are informed by the practical impact of policy on themselves or their members. When this is the case, NGOs are uniquely placed to respond to (a) the impact of government and business policies, (b) the impact of lack of policy, (c) failure to implement promises, (d) the unintended consequences of policy and (e) the existence of unethical or corrupt behaviour in business or government.

- NGOs are better than individuals trying to act on issues alone, because by pooling financial and intellectual resources they improve the quality of community input to public debate. ‘Two heads are better than one’ and ‘many hands make light work’.

- They improve equity in our society by providing a ‘voice’ (a) for minority groups and (b) for different geographical areas. Special interest groups such as the disabled, women and LGBT groups can be heard in public debate. Regional and country NGOs can provide information to make policy specifically relevant to different geographical areas. Input by these special interest groups helps refine public policy to benefit the common good.

- In contrast to government or large businesses, the NGO sector has flexibility to respond quickly to new political situations. That response can be in service delivery or policy. This flexibility can be seen as part of the variety, dynamism and vitality of the community from which NGOs come. The flexibility can also reflect different political and cultural ways of talking about the same issue and can tap into different parts of society. The richer the variety of NGOs in a society, the healthier is that society. An active community, engaged and debating creative proposals about public life, is to be desired, while at the other extreme, a society bereft of NGOs will veer dangerously towards totalitarianism or a dictatorship.

Traditional Role of NGOs

The political model of government, corporations and NGOs has always involved tensions. Votes for women, the anti-conscription campaign of the First World War, the Franklin Dam campaign and the consumer campaign against tobacco were all bitterly fought against government policies, with economic entities, such as the Tasmanian Hydro Electric Commission and tobacco companies being part of the mix. However, there was a social compact, or commonly held view of how our society functioned, that understood it was right for citizen organisations to speak for groups within society. NGOs were accepted as having an essential place in Australian society, despite many bitterly fought policy battles.

The acceptance of NGOs’ advocacy role was stated clearly in a 1991 statement by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Community Affairs.

An integral part of the consultative and lobbying role of these organisations is to disagree with government policy where this is necessary in order to represent the interests of their constituencies (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Community Affairs 1991).

In 1991, MPs believed public advocacy and criticism of government policy by NGOs was an essential activity.

Why has the role of the NGO sector been diminished?

During the 1980s, neoliberalism, or economic rationalism as we called it, influenced the economic policies of the Hawke government. By the mid 1990s, its influence had moved outside the normal economic sphere. New language emerged, in which human motivation was changed to an economic imperative. Individuals became ‘consumers’ and were described as behaving mainly in response to or in expectation of economic advantage or disadvantage to themselves. This was instead of human motivation being discussed in a holistic manner within the disciplines of psychology and sociology where there was a rich history on motivation that was inclusive of an individual’s social, intellectual, sexual and spiritual needs. Economic interpretations invaded other disciplines and, increasingly, the ‘market’ or economic motivation became the framework for much of our public discourse.

It is now almost a quarter of a century since John Howard first introduced a new language on the role of NGOs in Australian society based on this neoliberal or ‘market’ view. In so doing, he moved away from the idea of NGOs being the ‘third sector’ with equal importance to government and corporations. In two speeches associated with the Menzies Institute, Howard first suggested in 1995 that ‘mainstream’ Australia felt unable to be heard because of vested interest groups and that, if elected, he would change this and measure policy against the interests of ‘mainstream’ Australia (Howard 1995). The following year, after his election, he began speaking of ‘single-issue groups’, ‘special interests’, ‘elites’ and ‘accountability’ (Howard 1996). These were all words used by neoliberal economists believing that NGO advocacy would interfere with the efficient operation of the economy. Instead of the sector being of equal importance to government and corporations, it was described as ‘unaccountable’ because it was not elected. A process of undermining its legitimacy had begun.

Throughout the Howard Government, the theory of NGOs interfering with the market because of their advocacy was reflected in the Coalition’s language. It was also behind the initiatives they took to silence the sector. NGOs were commended for practical work such as feeding the homeless or planting trees, but advocacy was condemned. Organisations that disagreed with government policy experienced repercussions. This was the reverse of the House of Representatives Committee statement in 1991 that ‘an integral part’ of NGOs ‘lobbying role’ was to ‘disagree with government policy where this is necessary in order to represent the interests of their constituencies’.

Governments, including state governments, since Howard have continued attacks on the advocacy role of NGOs with many different initiatives aimed at silencing the sector. Over a quarter of a century, each step has whittled away the right of the sector to advocate (Staples 2012).

‘Confidentiality clauses’, which prevent organisations speaking to the media if they receive any government funding, have been one of the most effective silencing methods. Purchaser/provider contracts have skewed the work of many social service groups, who are now required to deliver specific ‘outcomes’ directly related to Government policy and objectives. At the same time, commercial providers, often the big corporate consultancy firms, have moved into the space previously occupied by social service and international development NGOs. The ability to claim tax deductibility as a charity has been under attack in one form or another since 2003 in attempts to restrict the incomes of NGOs. Coalition state governments have enacted laws aimed at the right of assembly. The list is long. It has been a quarter of a century of relentless attacks aimed at restricting the right to advocacy and protest.

Two New Attacks on NGOs

In December 2017, two new fronts were opened in Coalition government attacks. Firstly, the appointment of Gary Johns in December 2017 as director of the NGO regulator, the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) created incredulous disbelief and concern amongst NGO leaders. For decades, Johns has been proactive in criticising the public advocacy of NGOs and even their very existence. From 1997 to 2006 he headed the Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) NGO Watch, which ran vigorous campaigns attacking NGOs. His language was neither measured nor temperate. In a 2001 IPA publication, he even questioned the need for NGOs in a democracy saying, ‘In democratic societies with accountable governments, strong regulation of the corporate sector and an absence of endemic corruption in business-government dealing, the role of NGOs is problematic.’ In 2014, Johns was quoted as saying: ‘The Abbott government promised to abolish the Charities Act 2013, which includes advocacy as a charitable purpose. It must make good that promise in a way that makes it clear to the High Court that advocacy is not a charitable purpose’. Some of Johns’ more controversial comments in recent years included calling Indigenous women on welfare ‘cash cows’ and arguing for mandatory contraception for welfare recipients (Williams 2017).

The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC), which Johns now heads, was created with the support of the NGO sector in 2012 to ensure accountability and transparency, to support good governance and innovation in the sector and to promote the reduction of unnecessary red tape. As far back as 1995, the sector was looking for these outcomes in submissions to an Industry Commission Report, Charitable Organisations in Australia. The UK Charities Commission was seen as a model in the way it not only regulated NGOs, but also supported the sector with programs to develop best practice. Soon after his appointment, petitions calling for Johns’ removal appeared. However, his appointment is for a number of years. In the interim, the regulator of the NGO sector is headed by someone who for 30 years has called for the removal of the right of the sector to advocate.

Secondly, another front was opened attacking the sector in December 2017. Three ‘foreign interference’ bills were introduced, which treated NGOs as similar to political parties. The bills ignored the fundamental difference between political parties and civil society. Politicians and their parties form governments, and governments have the executive power to enact legislation that materially advantages or disadvantages organisations and individuals. In contrast, civil society cannot pass legislation. It can only advocate. The bills significantly affected international development NGOs, which work with many overseas governments to better the welfare of citizens in developing countries. Importantly, provisions threaded throughout the bills impacted the work of all NGOs.

A significant outcome has been the formation of a strong coalition of NGOs across all sectors calling itself, Hands Off Our Charities, which has lobbied strongly to amend the bills. It is likely that this strong coalition will continue after the bills are enacted. Over 40 major NGOs including a number of peak groups have decided that enough is enough and they need to jointly defend our democracy on a permanent basis. If this coalition stays together, it will be an important development in Australian NGO history.

Where do we go from here?

John Howard said he would change the country. His project has been successful in embedding neoliberalism within every aspect of our society – our way of talking, thinking and evaluating. Understanding the ‘unnamed’ theory under which we have laboured is the first step in rebalancing our rights.

Some older groups in the sector need to question whether their organisation needs renewal. Although neoliberal government policy has impacted heavily on NGO governance, neoliberal-inspired management has often been taken up by NGOs themselves, without regard to the implications. There was much criticism from neoliberal quarters during the Howard government that NGOs were ‘not accountable’. This was a reflection of the neoliberal world view that NGOs were not elected like governments and interfered with the ‘market’. Many in the sector misinterpreted this criticism as a need for better governance in the sector. It is true that better governance was often needed. Unfortunately many NGOs responded by introducing governance arrangements that echoed business boards dominated by professionals – fundraisers, risk management experts, accountants, communication experts – with little or no representation of those steeped in the sector’s democratic place. Many of those who did so lost an understanding of the important advocacy role of the sector – a factor that has led to its weakening. NGOs need good governance arrangements, but these need to be both appropriate for the size and nature of the organisation, and bureaucratic arrangements should not swamp or interfere with the advocacy aims of the organisation. Unfortunately we have seen too much of this managerialism weakening NGO action.

New dynamic groups led by young people need our support. The existential threat of climate change has created new organisations, particularly in the environment sector. Examples are organisations such as Tipping Point, which provides support to Stop Adani groups, Climate for Change, which reaches out to people who have not been involved in community advocacy on climate change, and the Australian Youth Climate Coalition, which is providing an entry point for people as young as school age. This renewal is not restricted to only the environment movement. For example, Democracy in Colour is a new NGO expressing the value of a multicultural society, and Young is an NGO dedicated to the welfare of young people. It is a new breed of young activists that has led this renaissance. They are determined, organised, open to new ways of organising and filled with energy and talent. ‘Community organising’ is a strong refrain, meaning they recognise the need to mobilise many people. They stand on the shoulders of older campaigners, such as those who, by mobilising large numbers, ensured the Franklin River still runs free. They have sometimes taken inspiration from the US, where the 2008 Obama presidential campaign is cited by many as providing inspiration on how to organise. The Occupy movement has focussed their attention on inequality – an important motivating factor for them. They also see the need for institutional change, such as reform of political party donation laws, and measures to address the ‘revolving’ door whereby industry, particularly the mining industry, has infiltrated government and regulators. These young campaigners are developing a vision of a better society and they need our support.

Strong bonds of trust have developed amongst NGOs while opposing the ‘foreign interference’ bills. This new coalition across many different parts of the sector could be significant. A voice providing proactive recognition of the value of NGOs and the value of our democracy is sorely needed.

So, rebalanacing our rights entails not just removing restrictions on NGO advocacy. It means NGOs need regular renewal. It means supporting the energy of new effective groups led by young leaders, and it means speaking in celebration of our democracy. The seven values of NGOs described earlier should be honoured and valued at every turn. Public discourse must celebrate the dynamism, vitality and fresh approaches which NGOs can offer to enrich our society. Australia should once again become proud that we have the rights of advocacy and protest.

References

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Community Affairs, 1991, You have your moments: Report on Funding of Peak Health and Community Organisations, AGPS, Canberra, p. 17-18.

Howard, J. 1995, The role of government: A modern liberal approach, Menzies Research Centre 1995 National Lecture Series, 6 June, Menzies Research Centre, <http://australianpolitics.com/1995/06/06/john-howard-headland-speech-role-of-govt.html>.

Howard, J., 1996, ‘The Liberal Tradition: The Beliefs and Values Which Guide the Federal Government’, 1996 Menzies Lecture, Sir Robert Menzies Lecture Trust, www.menzieslecture.org/1996, p. 2.

Monbiot, G. 2016, The Zombie Doctrine, https://www.monbiot.com/2016/04/15/the-zombie-doctrine/.

Staples, J. 2012, Non-government organisations and the Australian government: a dual strategy of public advocacy for NGOs, PhD Research thesis, UNSW, <https://joanstaples.org/publications/>.

Williams, W. 2017, Who is Gary Johns?, Pro Bono Australia, <https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2017/12/who-is-gary-johns/>.

Feature Image Photo: Bob Hawke Speaks At Franklin Dam Protest Rally. pszz. [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0]