In this conversation, hosted by Green Agenda co-editor Simon Copland, three speakers — Clare Ozich, Stephen Healy and Joan Staples — answered key questions about the nature of democracy. Panelists discussed what it is that we mean by ‘democracy’, why our democratic institutions are in crisis, and what we can do about it.

Thanks to the Green Institute for hosting such an engaging conference, and to Clare, Joan and Stephen for appearing on this panel.

Please also note that this session was interrupted by the announcement of the results of the ‘citizenship seven’, seven Australian MPs and Senators who were referred to the High Court over their dual citizenship. You will notice an interruption during Joan’s discussion in the second question.

Simon Copland: My name is Simon Copland, I’m one of the co-editors of Green Agenda and this is a Green Agenda panel/debate, titled “What even is democracy?”

The idea of Green Agenda is not to come to conclusions but to stoke debate about big ideas and so we thought that is what we wanted to do today . So we have three great panelists here, we have two questions that we’re going to be asking. The idea is that our panelists are going to give five minute responses to those questions, and then we are going to turn it over to you. And we are going to ask in your table to have a ten minute discussion about that question. We’ll do a little bit of a report back and then we’ll go to the second question and do the same.

So we have three great speakers today. I just want to quickly introduce our speakers.

Frst over here on your left is Clare Ozich. Clare Ozich is the founder and co-editor of Green Agenda. She has worked as a lawyer, an industrial officer in the union movement, and as director of policy for Greens leaders Bob Brown and Christine Milne. She’s currently the executive director of the Australian Institute for Employment Rights.

We then have Stephen Healy. Stephen Healy is a senior research fellow at the Institute for Culture and Society, University of Western Sydney and a recent arrival to Australia. He has a doctorate in geography, and his research focuses on community based approaches to sustainable economic development.

And finally, Joan Staples is a Melbourne based political scientist focusing on civil society and N.G.O.s, especially environmental N.G.O.s and their role in democracy. Her career has been in policy and advocacy working with national N.G.O.s involved in campaigns all over Australia and she has played a strong role in the formative years of the Greens.

So I’m going to start with you Clare and I’ll pass the microphone along. Our first question is what is needed to practice democracy? Whether in a group community or any level of government? And so this is a way of asking, what is democracy? What are its key elements, while noting democratic practice isn’t just for nations but lots of different aspects of engagement with our society?

Clare Ozich: Hi, good to see everyone here. Before I get on with what I was going to say, Green Agenda has published a few pieces exploring different aspects of democracy and three of the authors of those pieces are actually in the room today, which is really awesome.

So we’ve published Christine Milne, we re-published her analysis that Australia is no longer a democracy but is a plutocracy, so you can find that piece on Green Agenda. We’ve also published Joan on the role of N.G.O.s in our democracy and we have published Gary Shapcott on public space and public debate. So I would recommend all three of those pieces to you as well if you’re interested in democracy.

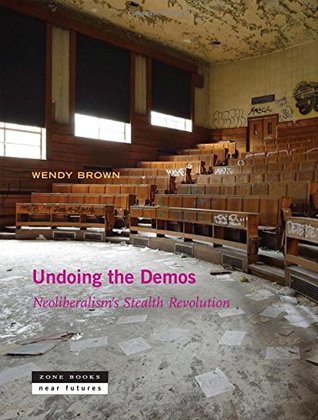

So I’m going to start with a quote from a U.S. academic called Wendy Brown who wrote a book called ‘Undoing the Demos’, which was an analysis of the hollowing out of democracy by neoliberalism. At the beginning she says this “Democracy is amongst the most contested and promiscuous terms in our modern political vocabulary. In the popular imaginary democracy stands for everything: from free elections to free markets, from protests against dictators to law and order, from the centrality of rights to the stability of states, from the voice of the assembled multitude to the protection of individuality and the wrong of the dicta imposed by crowds. For some democracy is the crown jewel of the West, for others it is what the West has never really had or is mainly a gloss for Western imperial and aims. Democracy comes in so many varieties: social, liberal, radical, republican, representative, authoritarian, direct participatory, deliberate, deliberative, plebiscite, that such claims often speak past one another”.

So I’m going to start with a quote from a U.S. academic called Wendy Brown who wrote a book called ‘Undoing the Demos’, which was an analysis of the hollowing out of democracy by neoliberalism. At the beginning she says this “Democracy is amongst the most contested and promiscuous terms in our modern political vocabulary. In the popular imaginary democracy stands for everything: from free elections to free markets, from protests against dictators to law and order, from the centrality of rights to the stability of states, from the voice of the assembled multitude to the protection of individuality and the wrong of the dicta imposed by crowds. For some democracy is the crown jewel of the West, for others it is what the West has never really had or is mainly a gloss for Western imperial and aims. Democracy comes in so many varieties: social, liberal, radical, republican, representative, authoritarian, direct participatory, deliberate, deliberative, plebiscite, that such claims often speak past one another”.

So it’s kind of in that context that we wanted to have this debate today and we’re talking about something that’s pretty big. But she goes on to say: “Accepting the open and incontestable significance of democracy is essential because I want to release democracy from containment by any particular form, while insisting on its value in connoting political self-rule by the people, whoever the people are”.

So she brings it back to this notion of self-rule by the people, whoever the people are. There are a couple of things in that obviously — self-rule, the notion of power, and a definition of democracy that it’s about the distribution of power. Then also of course the concept of the people. Who are the people, because this will change depending on what or context we’re in.

One of the fundamental core pillars of the Greens of course is participatory democracy and the principle that people affected by decisions should have a say in those decisions. So following on from that I want to focus not so much on the bigger picture of democracy and the state and parliaments and governance, but to talk a little bit about workplace democracy.

So as Simon said, my day job is that I work in the field of industrial relations. Workplace democracy is a pretty core part of having fair and decent work places. We all spend a fair amount of our time in various forms of work, whether it’s paid work or unpaid work. I had an event in Sydney on Wednesday for my job. We had a public debate on the workplace relations system and one of the speakers, an academic from UTS called Sarah Cane, spoke about workers voice and about how in Australia, basically workers are very much silenced. We have a legal system that silences workers, and part of that has come about from a shift in our workplace relations laws from a sense of the collective to a sense of the individual.

I mention this because I think that one of the key things about democracy is very much about how we create a collective amongst each other. And work is just one example of how we can do that, and an example also how we don’t actually do that very often. Many of us do that when we join a union. But there are obviously many other ways that we could have and practice democracy at work if we are in our workplace. This includes creating human connection with our fellow workers and coming together collectively to talk about what our interests might be. We can make decisions and exercise power in relation to our work, affecting both the conditions of the work but also how we perform our work.

The main point of what I’m wanting to say is that we have these laws and things that can stop us and dis-encourage us from talking with each other. I have lots of conversations with people and they want to know what they can do in their workplaces when their bosses aren’t being good to them and their fellow workmates. And you know apart from all the legal strategies, the first thing I say is just get your work colleagues together sit down and have a conversation with each other about what’s going on.

So I think workplace democracy is a really interesting example of both how democracy has been crushed, but also an example of where we as a society need to re-imagine a flourishing democracy. I’m not necessarily talking about institutionalised unions, although I think they’re really important. I think there are other ways you could practice democracy in your workplaces.

I just want to leave finally on this point, which is I think that workplace democracy is actually going to be a very key to addressing the climate crisis as well. Again coming from the bottom, workers knowing what’s going on in their workplaces and what needs to happen in their workplaces to be better in relation to the climate, I think is also really important aspect .

Stephen Healy: I got the e-mail from Clare and I didn’t actually see that particular question in there. I have questions like how can we meaningfully engage in political debate across societies and encompass difference? Do we leave it to the scientists or the experts or as does everyone get a vote? How can we use participation in participatory technologies, and something about the big state versus the small state?

But I like that question and I love Wendy Brown. I’ve only had a chance to see her once but she’s a very good speaker and one of the points that she makes in that book ‘Undoing the Demos’ is she says that there are other values that can animate political conversation. For example, what is the good, how are we supposed to care about one another? Increasingly what she says though is that neoliberalism is a kind of stealthy occupation of economisation of all life so that there’s only one thing that is to be done, and that’s a cost benefit analysis. And then by default what you get is the rule of experts. And then it’s no longer permissible to talk about other values. So that’s the stark picture that she leaves us with. But interestingly enough I don’t even think she’s the most depressing theorist out there about the state of democracy.

Just recently I came across a guy named Franco Bifo Berardi who was an Italian autonomist and he wrote a book called ‘Futurability – The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility’. Impotence is kind of a dirty word, but I’m going to use it anyways. Essentially what he says is that we are experiencing, and I think that he’s referring to the West, a condition of impotence. It’s very much the consequence of the neoliberalisation of life. And he goes further and says that, as artificial intelligence and automation takes hold and people are increasingly insecure about their economic lives, this condition of impotence takes expression in the form of a politics of reaction.

Just recently I came across a guy named Franco Bifo Berardi who was an Italian autonomist and he wrote a book called ‘Futurability – The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility’. Impotence is kind of a dirty word, but I’m going to use it anyways. Essentially what he says is that we are experiencing, and I think that he’s referring to the West, a condition of impotence. It’s very much the consequence of the neoliberalisation of life. And he goes further and says that, as artificial intelligence and automation takes hold and people are increasingly insecure about their economic lives, this condition of impotence takes expression in the form of a politics of reaction.

So this is his analysis, which he’s offering kind of ahead of the events that we’ve witnessed just over the last couple of years — from Theresa May’s Brexit to Trump’s America, to the rise of the authoritarian anti-immigrant rioting Germany, Austria, and Modi in India, Duterte in the Philippines, Erdoğan in Turkey.

So there’s this idea in Berardi’s analysis that impotence leads to this feeling of political reaction. So in a state of impotence democracy becomes a context in which people express this feeling of powerlessness and that takes the form of rage. Wendy actually, in a recent address in Germany called it a kind of wounded narcissism. When people feel like their ego, their sense of control and social status has been threatened by others, the tendency is to lash out. So this seems to be a current in social theory right now and we could go on and think of it in syntamalogical terms.

I mean look I don’t know, I’ve been grabbed by this kind of framework and I’ve been thinking as well that you know it also seems to find expression at least in the American culture and in the following way. There’s fifty thousand people a year that kind of look like me and are slightly older who are dying from the consequences of opioid addiction. And that’s a problem that white America knows about now but it’s been a problem in other communities for a lot longer. Or we can think about the violence turned outward, in you know sort of fits of incredible rage that have no apparent context. So for me if we’re going to think about what does it mean to recover a democratic ethos, and think big about it, I suspect those kind of operative cultural conditions that are under threat and it is that ability to live with others to engage.

How do we be hospitable with one another? I think what it means for me, is if we want to be democratic, if we want to be collective and self-governing, have meaningful autonomy in relation to our own lives and be able to live with others, what we need more than anything is spaces to practice it. And workplace democracy is something I’m really quite taken with is one of the settings for that, but I think there are others.

The worldwide recovery movement that deals with substance abuse and addiction is a great example. Those are individual groups that are autonomous and self-governing and then they have a global body that allows them to coordinate on matters of collective concern. So that’s an example that has an eighty year history, that’s international, that operates in twenty-six languages, and deals with one hundred eight different kinds of addiction problems on a democratic basis. But it’s the deep democracy card, where each group is self-supporting and autonomous. Maybe we could look for examples like that and recover different democratic traditions. I know I’m preaching to the choir and I know what’s already been done. The Transition Town movement for example has had a real discussions about how do you take that model and bring it into thinking about how do we come up with energy action plans and how do we as a community deal with ecological crises. We can extend that into social and economic ones as well.

I had other depressing stuff, but I can depress you further later on. That was sort of my opening hastily sketched out thoughts. I’ll hand it over to our friend.

Joan Staples: Clare and Simon asked us to be provocative and I thought I would draw your attention to some new research that was publicised back in, almost twelve months ago now, in December 2016. It said that democracy is under threat because young people are saying they’re fed up with democracy. Research from Harvard and from Melbourne University said the percentage that thought that it was essential to live in a democracy had fallen quite dramatically since the eighties. It’s mostly millennials in particular that weren’t very happy about it. And we were warned that this is about Trump and the rise of Hanson and those things, that people are fed up with Democracy.

The key sentence that I saw in this was that it was since the eighties. Our two previous presentations have referred to the rise of the neoliberal economics and neoliberal ideology, which has been happening since the 1980s; Thatcher, Reagan, and Keating and Hawke here.

The key sentence that I saw in this was that it was since the eighties. Our two previous presentations have referred to the rise of the neoliberal economics and neoliberal ideology, which has been happening since the 1980s; Thatcher, Reagan, and Keating and Hawke here.

I haven’t gone to that original paper yet to analyse it. I actually think that it’s only two researchers, and I need to look much more closely at their methodology to be sort happy with their findings.

I actually found some other research, which came out in March, which said that even though it looked like millennials were not engaging in democracy, they were able to indicate that there’s a huge number of ways in which they did actually engage in democratic processes.When they’re asked do they back democracy, most of them say that it only serves the interests of a few. 40% say that. And for statement “there’s no real difference between the policies of the major parties”, 32%. agreed But they also highlighted the role of young people, for example in Greece with the austerity movement, with Sanders and with Corbyn.

They also point to other research that in the U.K., which shows that young Britons are either more likely to volunteer, engage with social issues and are more likely to express their political opinions than earlier generations. I also went to the United States where the Pew Centre showed that social media users are more likely than their elders to post their thoughts on issues on political material, encouraging others to act on these political issues. So they might be weary of the formal voting calendar but they’re more likely than a forbears to get involved in grassroots campaigning.

What for me comes out of that is the message that what people are concerned about actually is the whole neoliberal ideology that’s been foisted on us since the 1980s. Distrust with democracy is really not necessarily the distrust of what is possible in the future, but rather distrust with where we are at the moment.

That rise of neoliberalism, which if you look at Hayek back in the thirties, there was some sense in coming up with this market based economic theory, when they’re opposing it against Communism and against Nazism. But as you move through the history and then you get the think tanks being set up, like the American Enterprise Institute and here the I.P.A. in 1940s, that were proposing that issue, and then the Chicago school coming on you see that big corporations recognised “oh this is not a bad theory you boys let’s get in, let’s promote this”. And so you have huge amounts going into promoting it. So we have actually had a developing of this theory for a long time until by the 1980s, with stagflation, we had Thatcher and Reagan and the Hawke/Keating Government begin to introduce those economic theories.

This whole sort of thinking has permeated right throughout our society. But it is, I believe, in the process of breaking down. I am very conscious as an academic, when I read through the literature on non-government organisations and the rise of progressive thought in the seventies, the academics didn’t predict that. They were all caught totally unawares. They did not see it coming. So I’m particularly conscious to put out my feelers of what is actually really going on in society, particularly with younger people. Not just focus on what the academics are saying.

I just finished attending, a week ago, the Australian Political Studies Association Conference as an academic. And I love to go along to see some of my good friends there, but I was shocked that academics are still talking about the old systems. They’re not looking at what’s coming, the fact that neoliberalism is cracking and how are we going to step in and put new things here. The academics there are missing out on what is I think some of the most exciting things that they could possibly be writing about. And it’s not all of them of course. Some of my best friends aren’t. But the majority are. So I just throw that in there that there is an interesting time coming and obviously we thank Green Agenda for putting this sort of on the cards.

But I think that what the immediate things are that certainly shown by what the three of us who got up to talk about, is that there is a dissatisfaction with neoliberalism. People are looking for community. We as green thinkers need to be thinking about the alternatives. Obviously we are here, you are the people who are thinking about those things. What do we actually want to put in its place? And I can’t do better than what the previous speakers have done in listing some of the prerequisites for respecting others. I would also throw in the importance I think of in any institutional type arrangements, whether it just be your local organisation running the community garden or whether it be government, I think the need for some sort of balance of power. We need to think about structures in which power is shared in some way. That very valuable contribution that Madison made to our debate on politics is that it’s important that we actually do set up our structures in that way that nobody can immediately become a dictator.

But the other issue is one of respect. We must have respectful debate and value different opinions in our interactions, the way in which we run our organisations, and the way in which we run our lives. This is a very subtle thing. Unfortunately some of those subtleties have been hit pretty hard by the sort of politics that we’ve been seeing recently. Now that doesn’t mean we have to accept that that’s the way things are. And I do think it is up to every one of us that value community, that value other values, to promote those, to talk about different values and to speak in a language that is from our heart, that represents human emotion that represents ethics in every way. I do feel that the community is hungry for that sort of language. To hear people in the public arena speaking with love and strength about ethical things that they really care about. So I’ll just leave it there and happy to talk some more later.

Simon Copland: So thank you to our three panellists for that initial discussion. It seems like we had some really great discussions here, which is exactly what we’re trying to achieve and so we’ve got now our second question that we’re going to ask, which is a big state or decentralised control? How do different understandings of democracy reflect your preference and how do, or can these two ideas exist? So when you go down the line at the other way and start with Joan, and we’ll just try and keep it short, and then we’ll come back and have another discussion.

Joan Staples: Yeah I’ll keep it really short. I’ve got two sort of ideas I want to touch base with you. I also want to be provocative too because I was told I had to be provocative.

Joan Staples: Yeah I’ll keep it really short. I’ve got two sort of ideas I want to touch base with you. I also want to be provocative too because I was told I had to be provocative.

It’s actually ironic isn’t it that in this era of globalisation that we’ve had this rise of local movements? You’ve got Catalonia, we’ve got Scotland, everywhere you look around the globe this has been happening more and more. Local individuality is coming out at the same time as the world’s shrinking and we’ve got this global way in which we all talk to another. I talk to actors all around the world and actually feel closer sometimes to people I know in other countries who work on the same issues than I do with people in my own street.

So it’s interesting sort of juxtaposition of the two. But my answer to this is that we need to be able to hold both in our head at once. That both are incredibly valuable and there’s no reason why it has to be big or small, we need all or both together.

I read a fantastic article yesterday about Northern Ireland and the complexities now that after Brexit they are going to have to cope with the fact that they can have a hard or a soft border there. It was also very illuminating to me in the way in which they actually solved the troubles in Ireland. In Northern Ireland you can choose to be British, Irish or both. Now legally that seems like that’s not possible, we think we have this nation state that you can’t be many different things. But it shows that there’s no reason why we cannot as human beings come up with creative solutions. And to me that was a lovely solution. Obviously they’re going to struggle now with Brexit and what they’re going to do about it, but I hadn’t really focused fully on that solving of the troubles, that you can have a British passport you can have an Irish passport you can have both.

[Joan’s talk interrupted by the announcement of the Citizenship Seven]

My other question, or the other thing I’d like to say is that, I actually am quite comfortable with appointing representatives to do things for me. I am so busy with all the organisations I belong to who want to have me involved in all of their decisions, I don’t have time to be involved in all those decisions. I trust people that I vote for that I want to elect to go and do that for me. I’ve got creative things I’m doing, I’m caring for my children, for my family. I’ve got my political work I want to do. I don’t have to worry about all that sort of stuff.

In the same way that I was vice president of Choice (a consumer advocacy group). I support having, when I want to buy something, having somebody else to help me, to tell me. I don’t have time to go and do all that work. It’s hard work to be a good consumer. I just want somebody to help. So that’s my provocative thing to you. I don’t want to have to decide everything about everything. Now I know that’s not what democracy means but it sometimes feels like that to me.

Stephen Healy: Tough act to follow. I’m reminded here of Groucho Marx’s response to the question “coffee or tea?”, and it’s of course it’s “yes please”. I would agree with you that it seems to me that large and small governments enable us to do different sorts of things.

I guess to reflect a bit more on what I was saying last time, I think there’s some serious curative or therapeutic work that needs to be done in order to rebuild an effective democratic culture. I can remember a colleague of mine who works in Appalachia, the ex-mining communities there who have been dealing with 75 years of intergenerational trauma associated with that the mining industry. He really felt like people couldn’t actually engage in the public sphere because of the kinds of depredations that they had been dealing with on an intergenerational basis.

So the recovery of a capacity to think collectively and make decisions I think requires serious effort on our part.

I feel like I was going to say something else too. Oh yeah, another example. I have a colleague who works in Maine on fisheries and he witnessed something a number of years ago that really up-ended the traditional way that fishery issues are dealt with. Usually it’s the state making big decisions about how to handle fisheries and communities suffering the consequences. So there’s a tension here between limits on catches and how fishing communities survive. His research intervention was essentially to create strategies for an adaptive co-management system. And these communities then turned around and started the first community supported fisheries like CSAs in my country. That model ended up spreading globally. So what they did was to say, well what if we actually considered the community as part of what we’re conserving? That changed the way biofisheries conservation got practiced, at least in that instance. So there’s a potential complementarity there between local governance, autonomy, economic practice and ultimately federal legislative policy in his work. His name is Kevin St Martin he’s gone on to basically add community as a data layer into fisheries sciences and that’s had global implications.

My thought here is that, well if that works for resource management we could probably make it work for health care and we could probably make it work for dealing with adequate mental health or addiction recovery services. There is a template there for how the particular and the general can relate to one another. It’s an expansion of our collective capacity to act.

But again it requires work and a particular kind of work and you know we’re all busy with meetings. I think it’s more a case of how do we integrate that practice into whatever it is that we’re doing with that larger vision in mind and I hope that’s helpful in some way.

Clare Ozich: I don’t disagree that it’s both, but we devised this question but, I think it’s also a tension in the broader politics on the left. There’s a tension there around the role of the state and how much trust actually we put in the state to do the things we want it to do.

I’m just reflecting a little bit more on what was said at the beginning about neoliberalism. One of the things that Wendy Brown writes about is how neoliberalism is not so much as a set of economic policies, but a political rationality. And so if you have a neoliberal state, do we trust the neoliberal state to do the things that we think that states should do to make our lives better? Well we don’t, do we we? And we shouldn’t, right? We shouldn’t, because neoliberal states are operating from a set of values that aren’t our values. They’re operating from, as Joan articulated, the sense that the economic dominates. So I think there’s a question there about the nature of the state when we’re considering this question.

When we were sort of pulling this session together I was originally inspired by Margaret (Blakers), thinking about framing the whole debate around energy systems. That’s one of the areas where this debate around the state and centralised provision of energy versus the sort of radical democratic potential of renewable energy, there’s a bit of tension there now. We need the state, I’m not saying we don’t need the state. But the decisions the state makes around our energy systems are going to be reflective of whether or not we’re going to be able to recognise the sort of democratic potential of renewable energy, or whether the state’s going to hold on and we’re just going to see basically a neoliberal centralised renewable energy sector.

When we were sort of pulling this session together I was originally inspired by Margaret (Blakers), thinking about framing the whole debate around energy systems. That’s one of the areas where this debate around the state and centralised provision of energy versus the sort of radical democratic potential of renewable energy, there’s a bit of tension there now. We need the state, I’m not saying we don’t need the state. But the decisions the state makes around our energy systems are going to be reflective of whether or not we’re going to be able to recognise the sort of democratic potential of renewable energy, or whether the state’s going to hold on and we’re just going to see basically a neoliberal centralised renewable energy sector.

I guess one of the points of this question was to sort of acknowledge that there’s a bit of a tension there and it’s one I think that we need to be aware of, and to keep thinking through and have in the front of our minds when we’re thinking about a bunch of stuff. That’s just one example I think of how that tension is going to play out in the next few years.