The story of the abolition of the Transatlantic slave trade reads like a modern NGO advocacy campaign. Most of us know of Wilberforce who was its parliamentary spokesperson, but the campaign was much more than Wilberforce. It was the birth of the modern community organising campaign.

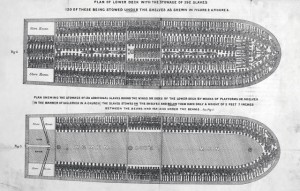

The abolitionists had their headquarters in London with branches in towns all over Britain. Their lead-organiser was Thomas Clarkson, who used serious research, combined with practical show-and-tell sessions to motivate the public. He travelled the length and breadth of Britain setting up groups, speaking tirelessly, showing artifacts, such as slave leg irons, to emphasise the horrible reality of the trade. The groups were largely self-organising, but they shared materials or information much as activists do today. There were petitions, songs, poetry, and much creative campaigning. They even had a logo of a kneeling slave. Josiah Wedgewood the pottery entrepreneur, who was a supporter of the campaign, made a pendant of the logo, which was worn by women supporters. A former slave, Equiano, spoke to activist groups, providing a human face for slave resistance.  A poster showing how hundreds of slaves were crammed into boats had an 8,000 copy first printing. It was snapped up by the groups who distributed it far and wide. Amazingly, the grass roots rose up with an economic boycott of sugar that was not endorsed by the parliamentary leadership. It was led by women who refused to buy sugar produced with slave labour. Over 300,000 households participated, and notably it was women who were the dominant activists and organisers, despite not having the right to vote.

A poster showing how hundreds of slaves were crammed into boats had an 8,000 copy first printing. It was snapped up by the groups who distributed it far and wide. Amazingly, the grass roots rose up with an economic boycott of sugar that was not endorsed by the parliamentary leadership. It was led by women who refused to buy sugar produced with slave labour. Over 300,000 households participated, and notably it was women who were the dominant activists and organisers, despite not having the right to vote.

This is a campaign story that will sound familiar to modern activists, and it is a legacy they should proudly own.

What is the place of NGOs in our democracy?

The emergence of this type of activism 200 years ago went hand in hand with the development of modern representative democracy that we know today. It has been an essential part of the British and Australian representative system. John Anderson, the eminent Australian philosopher, saw participation in NGO organisations as central to our democracy. He said,

Independent activity, involving at times, opposition to the State, is not opposed to democracy; it is essential to it. Democracy resides in participation in organisations, in the openness, the publicity, of struggle. ((John Anderson was the high-profile Professor of Philosophy at Sydney University from 1927 to 1958 where he influenced a generation of thinkers and activists.))

Representative government means that we do not have direct democracy like the free male citizens of ancient Athens. Instead, NGOs ((I am using the name ‘NGOs’, short for non-government organisations, but the sector has many names – the community sector, civil society, not-for-profit sector, the voluntary sector, the third sector, the social economy, charities, public interest groups. I am particularly interested in the role of those NGOs that include advocacy for the benefit of the community as part of their work.)) fill the representative gap, which has been named by political scientists as the ‘democratic deficit’ ((Hindess, B. 2002, ‘Deficit by Design’, Australian Journal of Public Administration, vol.61, no. 1, pp 30-38.)). Our representative system has NGOs playing a mediating role between the state and the individual. They provide a flexible, variable and effective way for individuals to relate to the political system. The power, size and inaccessibility of modern governments make the mediating role of NGOs even more important.

The following diagram is a model often used by social scientists to describe society and the relationship of its three democratic elements – government/state, corporations/market, and community/NGOs. ((It is also a graphic representation that helps explain the name, ‘the third sector’, which is common in the UK and often favoured by academics.)) Each sector is important in its own right, yet each depends on and compliments the other. The community/NGO sector is as important as government and corporations. The diagram demonstrates the uniqueness of each sector, and that the boundaries between them sometimes merge, but that each plays an essential and equal part in the functioning of a modern democratic society.

The following diagram is a model often used by social scientists to describe society and the relationship of its three democratic elements – government/state, corporations/market, and community/NGOs. ((It is also a graphic representation that helps explain the name, ‘the third sector’, which is common in the UK and often favoured by academics.)) Each sector is important in its own right, yet each depends on and compliments the other. The community/NGO sector is as important as government and corporations. The diagram demonstrates the uniqueness of each sector, and that the boundaries between them sometimes merge, but that each plays an essential and equal part in the functioning of a modern democratic society.

Unique Role of NGOs in Society

If NGOs are important in their own right, what is this mediating they do? We can identify seven positive contributions they make that are part of their unique role as this third sector.

Their comment on policy is vital to good policy-making by both government and business. People on the ground can see and predict the effect of policies more effectively and so make improved outcomes possible for all. The relationship need not be a confrontational one and earlier Australian governments, such the Hawke government, actually went out of their way to set up advisory committees of NGO representatives to glean ideas and refine policy.

Importantly, NGOs are uniquely placed to support policy that looks to long term goals, or policy that affects the future. Governments react to the short electoral cycle, asking ‘how will it affect our chance of re-election?’. Businesses have a legal responsibility to ask ‘how will it affect our bottom line’?. It is a special quality of the NGO sector that it has the flexibility to include the long-term in its policy interests and in its desired outcomes. What better issue than climate change to demonstrate this point?

A well-functioning society needs a balance between the power of government, economic interests and the community.

The sector also provides a check against the views of powerful, organised, economic interests. There is a large imbalance between the power of vested interests and that of the community. A well-functioning society needs a balance between the power of government, economic interests and the community. There is inevitably a healthy tension between the three sectors, but keeping the balance of power between the sectors is the challenge faced by a democracy. If governments and business align too strongly and too often, the community sector suffers and the democratic system is weakened.

NGOs have an accountability function. They inform the community about the behaviour of governments and businesses and call them to account. NGOs can claim legitimacy for this role if their roots are in the community and they are informed by the practical impact of policy on themselves or their members. When this is the case, NGOs are uniquely placed to respond to (a) the impact of government and business policies, (b) the impact of lack of policy, (c) failure to implement promises, (d) the unintended consequences of policy and (e) the existence of unethical or corrupt behaviour in business or government.

NGOs are better than individuals trying to act on issues alone, because by pooling financial and intellectual resources they improve the quality of community input to public debate. ‘Two heads are better than one’ and ‘many hands make light work’.

They improve equity in our society by providing a ‘voice’ (a) for minority groups and (b) for different geographical areas. Special interest groups such as the disabled, women and LGBT groups can be heard in public debate. Regional and country NGOs can provide information to make policy specifically relevant to different geographical areas. Input by these special interest groups helps refine public policy to benefit the common good.

In contrast to government or large businesses, the NGO sector has flexibility to respond quickly to new political situations. That response can be in service delivery or policy. This flexibility can be seen as part of the variety, dynamism and vitality of the community from which NGOs come. The flexibility can also reflect different political and cultural ways of talking about the same issue and can tap into different parts of society. The richer the variety of NGOs in a society the healthier is that society. An active community, engaged and debating creative proposals about public life is to be desired, while at the other extreme, a society bereft of NGOs will be totalitarian or a dictatorship.

Early 20th Century Australia

This political model has always involved tension with government and business. Votes for women, the anti-conscription campaign of the First World War, the Franklin Dam campaign and the consumer campaign against tobacco were all bitterly fought against government policies, with economic entities, such as the Tasmanian Hydro Electric Commission and tobacco companies being part of the mix. However, there was a social compact, or commonly held view of how our society functioned, that understood it was right for citizen organisations to speak for groups within society. NGOs were accepted as having an essential place in Australian society, despite many bitterly fought policy battles.

During the 1980s, the Hawke government tried to formalise or corporatize the relationship with an emphasis on peak NGO bodies and advisory committees. As Australian Conservation Foundation representative in Canberra at the time, I experienced much pressure from the ALP’s Graham Richardson for the environment movement to create a peak body ‘like the ACTU’ – something we always resisted. The Hawke government also funded advisory groups such as the National Women’s Consultative Council and the National Consumer Affairs Advisory Council. Some of this formalising of relationships was undoubtedly intended to make the government’s interaction with the NGO sector more manageable for them, but that does not detract from the argument that NGOs were still considered an integral part of the healthy functioning of our society.

The acceptance of NGOs’ advocacy role was stated clearly in a 1991 statement by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Community Affairs.

An integral part of the consultative and lobbying role of these organisations is to disagree with government policy where this is necessary in order to represent the interests of their constituencies. ((House of Representatives Standing Committee on Community Affairs, 1991, You have your moments: Report on Funding of Peak Health and Community Organisations, AGPS, Canberra, p. 17-18.))

In 1991, MPs believed public advocacy and criticism of government policy by NGOs was an essential activity. Perhaps this statement was also an attempt to stand against new interpretations on the role of the sector that were emerging during the 1990s.

Neoliberalism and New Political Thinking on NGOs in the 1990s

During the 1990s a new wind swept through Australian society. Neoliberalism, or economic rationalism as we called it, influenced the economic policies of the Hawke government in the 1980s. By the mid 1990s, the influence of neoliberalism had moved outside the normal economic sphere. New language emerged, in which human motivation was changed to an economic imperative. Individuals were described as behaving mainly because of economic advantage or disadvantage to themselves. This was instead of human motivation being discussed in a holistic manner within the disciplines of psychology and sociology where there was rich history on motivation that was inclusive of an individual’s social, intellectual, sexual and spiritual needs. Economics interpretations invaded other disciplines, and increasingly, the ‘market’ or economic motivation became the framework for much of our public discourse.

It is now twenty years since John Howard first introduced a new language on the role of NGOs in Australian society based on this neoliberal or ‘market’ view. In so doing, he moved away from the idea of NGOs being the ‘third sector’ with equal importance to government and corporations. In two speeches associated with the Menzies Institute, Howard first suggested in 1995 that ‘mainstream’ Australia felt unable to be heard because of vested interest groups and that, if elected, he would change this and measure policy against the interests of ‘mainstream’ Australia. ((Howard, J. 1995, The role of government: A modern liberal approach, Menzies Research Centre 1995 National Lecture Series, 6 June, Menzies Research Centre.)) The following year after his election he began speaking of ‘single-issue groups’, ‘special interests’, ‘elites’ and ‘accountability’. ((Howard, J., 1996, ‘The Liberal Tradition: The Beliefs and Values Which Guide the Federal Government’, 1996 Menzies Lecture, Sir Robert Menzies Lecture Trust, accessed at www.menzieslecture.org/1996, p. 2..)) These were all words used by neoliberal economists believing that NGO advocacy would interfere with the efficient operation of the economy. ((Staples, J. 2006, NGOs out in the cold: The Howard Government policy towards NGOs, Discussion paper 19/6, Democratic Audit of Australia, www.joanstaples.org/publications.)) Instead of the sector being of equal importance to government and corporations, it was described as ‘unaccountable’ because it was not elected. A process of undermining its legitimacy had begun.

Economics interpretations invaded other disciplines, and increasingly, the ‘market’ or economic motivation became the framework for much of our public discourse.

Throughout the Howard government the theory of NGOs interfering with the market because of their advocacy was reflected in the Coalition’s language. It was also behind the initiatives they took to silence the sector. NGOs were commended if they did on the ground practical work of feeding the homeless or planting trees, but advocacy was condemned. Organisations that disagreed with government policy experienced repercussions, including defunding. This was the reverse of the House of Representatives Committee statement in 1991 that ‘an integral part’ of NGOs ‘lobbying role’ was to ‘disagree with government policy where this is necessary in order to represent the interests of their constituencies’.

Recurrent or core funding disappeared to be replaced by purchaser/provider contracts in which NGOs delivered specific ‘outcomes’ directly related to Government policy and objectives, and commercial providers began to be favoured to deliver outcomes for work previously done by social service and international development NGOs. Probably the most effective silencing method was placing gag clauses in the contract of any NGO receiving government funding. The clauses prevented organisations from speaking to the media. They had a chilling effect and NGO voices began to disappear from the airwaves and print, both because of the gag and because of self-censorship from fear of repercussions.

Today the removal of tax deductibility of NGOs is on the agenda, but the idea first emerged in a different form in 2003 as a proposed Charities Bill. Amongst the Bill’s proposals was the provision that charity status would be removed if organisations attempted ‘to change the law or government policy’ in a way that was ‘more than ancillary or incidental’ to its other purposes’. The sector responded energetically, and hundreds of responses to an inquiry were received. There were many aspects of the Bill that were unworkable, and combined with significant opposition from some of the churches, in the lead-up to the 2004 election the Government decided not to continue with the proposal.

However, following a resounding win at the election including gaining control of the Senate, the attempts at silencing resumed. The ATO released draft rulings that restricted advocacy and there were changes to the Electoral Act requiring continual reporting of funding sources.

They were difficult times for NGOs. The Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) was running an active campaign called ‘NGO Watch’ with former Labor Minister, Gary Johns, as campaign director. Its many proposals were often reflected in the actions of the Howard government and its publicists used language denigrating the democratic role of NGOs. In one article, Johns referred to ‘cashed up NGOs’, ‘a dictatorship of the articulate’, a ‘tyranny of the articulate’ and a ‘tyranny of the minorities’, ((Johns, G., 2000, ‘NGO way to go: Political accountability of non-government organisation in a democratic Society’, IPA Backgrounder, 12, 3, November, p. 4-5.)) and in another to, ‘mail-order memberships of the wealthy left, content to buy their activism and get on with their consumer lifestyle’. ((Johns, G., 1999, ‘NGOs: Lazy Activism’, Australian Financial Review, 6 December.)) Today, Johns has left the IPA and set up a new think-tank, the Australian Institute for Progress, where he continues his NGO attacks and exhorts the Abbott government into action.

The Labor Governments of Rudd and Gillard saw the removal of gag clauses and a less confrontational approach to the role of NGOs. This was helped by a David and Goliath case in which the tiny NGO, AidWatch, took on the Australian Tax Office (ATO) and, after a battle of many years, won a case in the High Court in 2010. The Court affirmed that political activity was a legitimate charitable activity. The resulting ATO ruling, which still stands, makes it clear that it is legitimate for charities to advocate publicly, in fact there is no limitation on charities if their purpose is to influence legislation, government activities or policies.

However, John Howard said he would change the country and he did. A decade of neoliberal language and attitudes can affect a whole generation and those coming to maturity in the past 20 years have known no other. Many Australians now see society through neoliberal eyes without realising their view has been formed by the political environment and the dominant public narrative heard daily. The NGO sector has a tough job to define itself outside that paradigm.

Managerialism in NGOs

Neoliberal management practices have impacted heavily on the governance of NGOs and have often been taken up by NGOs without giving due regard to their implications. There was much criticism from neoliberal quarters during the Howard government that NGOs were ‘not accountable’. This was a reflection of the neoliberal world view that NGOs were not elected like governments and interfered with the ‘market’. Many in the sector misinterpreted this criticism as a need for better governance in the sector. ((Staples, J. 2008, ‘Attacks on NGO “accountability’: Questions of governance or the logic of public choice theory?’, in J. Barraket (ed.) Strategic Issues for the Not-for-profit Sector, UNSW Press, Sydney.)) It is true that better governance was often needed. Unfortunately many NGOs responded by introducing governance arrangements that echoed business boards dominated by professionals – fundraisers, risk management experts, accountants, communication experts – with little or no representation of those steeped in the sector’s democratic place. Many of those who did so lost an understanding of the important advocacy role of the sector – a factor that has led to its weakening.

How this has happened owes something to the practice of New Public Management in the public service and to neoliberal theory of how to run organisations. New Public Management is a name given to a range of neoliberal reforms that began reshaping the public sector and approaches to service delivery from the late 1970s and continued throughout the 1980s and ‘90s. Bureaucracies that had delivered the welfare state were opened up to competition and reorganised according to market theories of neoliberalism. Delivery of services was moved to private providers who competed with each other to win government contracts. It was done with the aim of ‘reducing the size of government’, while workplace ideas of equity and service were replaced with the idea of providing ‘rewards for quantifiable individual performance’. ((Brett, J. 2003, Australian Liberals and the Moral Middle Class, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p. 172.)) During the Keating years, competition policy and the microeconomic reforms from the Hilmer Report of 1992 reinforced a process that treats all citizens as consumers, emphasising economics as opposed to social goals.

There were big implications for the social service sector and other sectors that had been dependent on government funding to deliver services. They now found themselves competing with the private sector for funding. The result was that they responded by transforming their governance to echo that of the corporate/private sector.

NGOs need good governance arrangements, but these need to be both appropriate for the size and nature of the group, and bureaucratic arrangements should not swamp or interfere with the advocacy aims of the organisation. Unfortunately we have seen too much of this managerialism weakening NGO action.

There are some green shoots within the NGO sector that are reinvigorating sector’s advocacy role and moving away from excessive managerialism. New younger environmentalists inspired to respond to climate change have been ‘building power’ by relearning community organising and reaching out across different sectors to strengthen their advocacy. However, the wider sector is struggling to find its role as attacks continue from the Abbott government. Managerialism is sometimes a hindrance.

The Abbott Government

The Howard years can be described as a government trying to implement policies that were consistent with neoliberal views on the market and society. The result was frequently advantageous to the corporate sector, but Howard government representatives mostly couched their language in consistent neoliberal terms, such as small government and no advocacy by NGOs. In contrast, the Abbott government has gone much further. Its consistency appears to be that it attacks any opposition in a continual confrontational stance, and it will go so far as to flout democratic governance such as the division of powers and due process. ((For example, Cabinet has decided to give a Minister the power to remove the citizenship of persons without recourse to any court process; and Gillian Triggs, President of the Human Rights Commission has been accused by Immigration Minister, Peter Dutton, of being a ‘political advocate’ because of statements that fulfil her legal mandate to speak on human rights.)) Current attacks on the NGO sector by the Abbott government display a close association between government and corporations, particularly the mining sector. The balance between the three sectors (government, corporations and community) has broken down. Government Members and the Minerals Council of Australia appear to speak as one in attacking the NGO sector, particularly environmental NGOs. The virulence of the attacks on the sector are from a government whose partisan behaviour is unprecedented in Australia.

In June, 2014 the Liberal Party federal council unanimously recommended stripping NGOs of their ability to receive tax-deductible donations. This is a theme that has been pushed by Gary Johns, the Minerals Council of Australia, and George Christensen, the Member for Dawson in north Queensland. Christensen called for a ‘cleansing’ of the Department of Environment’s list of tax deductible recipients and described environmental NGOs as ‘terrorists’. After the scene had been set by inflammatory comments from these parties, in March 2015 the Government announced a House of Representatives Inquiry into the tax deductibility of environmental NGOs.

It should be noted that it is not an Inquiry into the tax deductibility of other NGOs, neither does it include the IPA, the Chifley Research Centre nor Menzies House, who all share the same ability to offer donors the advantage of tax deductibility. There also appears to be no problem with corporations claiming the work of their lobbyists as a deductible expense. Neither is there a problem with donations to political parties being tax deductible. The focus of the Inquiry appears to be that NGOs should do ‘on ground works’. They should not advocate. ((Burdon, P. 2015, ‘Government inquiry takes aim at green charities that ‘get political’’. The Conversation, 16 April.))

The Minerals Council of Australia has also been proposing the removal of an exemption in the Section 45DD of the Competition and Consumer Act to stop NGOs from campaigning against the environmental behaviour of companies, and Richard Colbeck, Parliamentary Secretary for Agriculture, has enthusiastically supported this idea. The Minerals Council is also concerned by the rise of the movement encouraging divestment from fossil fuels and is calling for charges to be laid under Section 1041E of the Corporations Act. The Minerals Council’s members are the largest and most powerful mining companies operating in Australia. ((In May 2015, board membership included representatives from MMG Limited, Glencore, Newcrest Mining, Paladin Energy, Wesfarmers Resources, Anglo-American Coal, Rio Tinto Australia, AngloGold Ashanti Australia, Toro Energy, BHP Billiton, Peabody Energy, EDI Mining and Newmont Asia Pacific.))

As the need for climate change action has become more pressing, young environmental activists have been stepping up campaigns against coal seam gas and coal extraction, as well as divestment from fossil fuels. At the same time, the cost of alternative energy has dropped dramatically. The community interest looking into the future is clashing with the short term economic interests of the mining industry. In this clash of values and economic interests the Abbott government has aligned itself closely with the mining industry. ‘Coal is good for humanity’, says Abbott. Tasmanian MP Andrew Nikolic accuses the Australian Conservation Foundation, the Bob Brown Foundation and the Environmental Defenders’ Offices, of “untruthful, destructive attacks on legitimate business” and “political activism”, MP George Christensen calls NGOs ‘terrorists’ and the government is ambivalent as to whether it believes climate change is real or not.

George Brandis, the Attorney-General, has also been busy removing funding from the national legal network of Environmental Defenders Offices, but his interest has been wider than the environment. He has also changed the service agreements of the national network of community legal centres to prevent them publicly suggesting legal reforms or engage in public debate and advocacy.

The rest of the NGO sector has not been immune. In August 2014, Cassandra Goldie, CEO of the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) warned that her member groups feared retaliatory action should they comment critically on government policy. This followed defunding of groups supporting financial advice for low income earners, housing, drug and alcohol counselling and youth affairs. Indigenous groups have also been targeted with the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples defunded.

One of the most pointed attacks on an NGO critical of government policy was the defunding of the Refugee Council by Scott Morrison the Immigration Minister in May 2014. The defunding was a sudden intervention by the Minister with no notice given and was done just two weeks after its funding was guaranteed in the Federal Budget. The ‘Stopping the boats’ slogan with punitive measures against asylum seekers is a core policy of the government and the Refugee Council’s human rights concerns have been swept aside by a poor process and Ministerial whim.

The balance between the three has been tipped in favour of government and corporations equating their interests, at the expense of the community sector and the public interest.

The breadth of the assault on civil liberties, on NGOs themselves and on the right to hold corporations and the government to account does not stop with the Federal Abbott government. Conservative state governments have also been proposing laws intended to remove rights of assembly and protest. Queensland, NSW, Victoria, Tasmania and Western Australia have flirted with legislation. In most cases the legislation would give broad powers to police and criminalise peaceful public protest.

Australia in 2015

Australia in 2015 is in danger of losing something fragile and valuable – our social contract between government, corporations and the community. The balance between the three has been tipped in favour of government and corporations equating their interests, at the expense of the community sector and the public interest. The proud tradition of the anti-slave trade activists that was handed down to Australia and its NGO sector is being trodden underfoot by language and policies that abhor the richness of public debate and the energy of community empowerment.

Yet, retrieving the legacy may still be possible. The monumental clash of values between those wanting to address climate change and those wanting business as usual throws up possibilities that Naomi Klein explores in her book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate. ((Klein, N., 2015, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate, Penguin.)) She challenges NGOs to join together to address, not just climate change, but neoliberal policies and practices welded by those currently in power. Those policies and practices in relation to NGOs are spelt out in this essay. They lead to the conclusion that business-as-usual for the sector will no longer work. The attacks on NGO legitimacy are serious and cannot be papered over by trying to operate as if they were not happening. The challenge for Australian NGOs, environmental and otherwise, is to take Klein’s challenge, join together and tackle the big picture of neoliberal repression, while at the same time continuing their work with the issues they currently address.