On the 9th December, 2016, the Green Institute published the paper Can Less Work be More Fair: a discussion paper on Universal Basic Income and Shorter Working Week. As part of this release Green Agenda will be republishing a number of essay from the paper.

The third paper we are publishing is from Louise Tarrant, “Goin’ where the weather suits my clothes“.

How might a Universal Basic Income (UBI) and shorter working hours interact with challenges facing democracy, civil society and community engagement?

Everybody’s talking about it …

Brexit and Trump have done for democracy what Occupy did for inequality—everybody’s talking about it.

That’s the refrain that keeps looping in my head—everybody’s talking about it. And I keep coming back to it like an annoying lodestar.

So I look it up and am reminded it’s a Harry Nilsson hit— “Everybody’s talkin'”.

Satisfied, I go back to writing. But something keeps drawing me back to those lyrics:

Everybody’s talkin’ at me

I don’t hear a word their sayin’

Only the echoes of my mind

People stop and stare

I can’t see their faces

Only the shadows of their eyes

I’m goin’ where the sun keeps shinin’

Through the pourin’ rain

Goin’ where the weather suits my clothes

They make me pause. These lyrics somehow fit because, fundamentally, democracy is a story about people. Yes, it’s also about polls, voting systems and candidates—but that’s just the mechanics. At its heart, democracy is about people coming together as a community to be heard, to debate, to be represented, to share the hardships and the good times and to have their collective ambitions realised for a better life. It is an intensely human endeavour and a collective one.

But what happens when people’s stories get lost?

Everybody’s talkin’ at me

I don’t hear a word their sayin’

Only the echoes of my mind

What happens when people feel cut loose—facing the future on their own?

Sometimes people organise.

Sometimes people retreat.

Sometimes people look for champions … for rebels who see them, or at least touch their anger. And suddenly people who have been absent from the political spotlight assume centre stage in unexpected ways.

People stop and stare

I can’t see their faces

Only the shadows of their eyes

But is the moment fleeting, or is their shout-out a pivot point? Arguably there have been several seminal pivot points for western democracies in the last 70 years.

First pivot: People before capital

After two World Wars and a Depression, social democracies embraced a political agenda that put people and their collective aspirations at its heart. A social compact with capital was forged that promised shared prosperity, full employment and a properly funded welfare state.

I’m goin’ where the sun keeps shinin’

Through the pourin’ rain

Goin’ where the weather suits my clothes

That’s how people must have felt: a grand vision that made space for people to raise families, rebuild lives, work with dignity, and embrace the future with optimism.

Yes, it could have gone further and it certainly wasn’t without contest, but the spectre of communism and the constant push of an organised labour movement kept employers engaged and social democratic parties rooted.

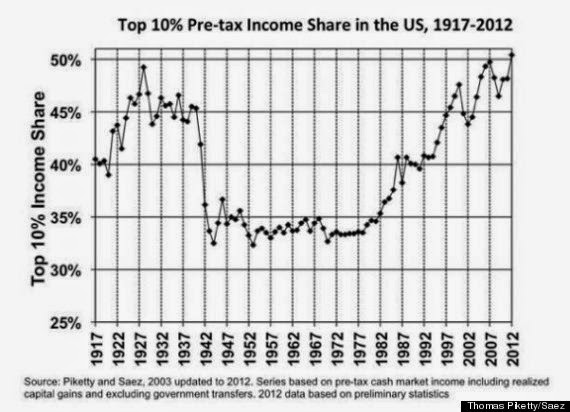

It was no accident that three decades of economic growth ensued, and as the Saez-Piketty graph attests, the shift in income to the top flatlined and everybody’s boat did indeed rise.

Second pivot: People to people

An extraordinarily short pivot of just a few years stormed the Australian polity with the Whitlam government in the early 1970s. I remember attending a function where a whole raft of ALP members were being recognised for their 40-year party membership. Without fail they talked of the excitement of that period: new thinking; embracing people focussed change such as healthcare, education, family law, urban planning. That is what drew them into political activism.

I’m goin’ where the sun keeps shinin’

Through the pourin’ rain

Goin’ where the weather suits my clothes

Third pivot: Capital before people

But, just as “Everybody’s Talkin’” was topping the charts in 1970, capital was getting organised, particularly in the US and UK, around an alternate agenda—one based on market values and market freedoms. Money, not people, was at the heart of their story.

Many governments embraced this shift and a new era—neoliberalism—was born.

The next 40 years were to be characterised by aggressive pursuit of:

- Deregulation—particularly of labour, environmental, trade and finance laws—basically anything that got in the way of the ‘free’ operation of the market; • De-taxation—intended to both shift the tax take from businesses and the wealthy and starve state coffers;

- Privatisation—selling off public assets and opening up of ‘new markets’ for private business;

- De-collectivisation—breaking unions and undermining other advocacy organisations;

- De-politicisation of the public—individualising issues, shifting risk from employers to workers, equating citizens with consumers, offering choice in lieu of agency; and

- Politicisation of business—financing of elections and deep lobbying with governments. The social compact was torn up. People became commodities in a marketplace.

Fourth pivot: Capital doubles down

Then, in 2008, we saw the ultimate failing of that neoliberal economic contract—a contract that had mandated a reduced role for government in stabilising markets and increased freedoms for capital to operate at will.

![By Jonny White (G20 April 1st) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://greenagenda.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/G20_capitalism_banner-300x200.jpg)

Ever since, millions of people across western democracies have paid the price—jobs cut, homes repossessed, savings gutted, retirement deferred. As tax payers bailed out business, an acceleration of the wealth transfer from workers to capital proceeded. This pivot point is particularly important because, instead of becoming a pivot point of resistance and rebalancing, it has actually seen governments deepening their commitment to a failed strategy.

Everybody’s talkin’ at me

I don’t hear a word their sayin’

Only the echoes of my mind

But perhaps the biggest loser from the last few decades has been democracy itself. Understanding this is key to us organising for the next pivot point.

‘Efficiency, flexibility, growth’ became the new language of political leadership, while the lexicon of fairness and rights was discredited or lost.

The hollowing out of democracy

I would argue that social democratic parties giving primacy to their partnership with capital over the last 40 years has fundamentally weakened core tenets of what makes for a healthy mass democracy.

Listed below are five areas of deficit—with two themes resonating throughout:

- the de-politicisation of politics; and

- the effective exclusion of citizens’ voices from the polity

1. Champions lost

People saw political leaders and social democratic parties morph into economic managers rather than political champions of the public interest. ‘Efficiency, flexibility, growth’ became the new language of political leadership, while the lexicon of fairness and rights was discredited or lost.

Everybody’s talkin’ at me…

2. Loci shifted

Not only was the supposed level playing field tilted to the capital class, but the playing field itself became harder to find. The previous rules of the system were clear—distribution got decided with employers at the bargaining table, and with political parties at the ballot box. There were rules, and people had rights and a role. But this period saw decision-making shifted to new arenas: the finance sector, global corporations, ratings agencies, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) policies—places and processes in which workers and citizens had few rights or pathways. ((Streeck, Wolfgang, Buying Time—the delayed crisis of democratic capitalism, Verso, London, 2014 p.46.))

Everybody’s talkin’ at me

3. Muscle eviscerated

Unions, instead of being seen as social partners in the raising of standards, became the enemy. Governments did the bidding of business, erecting barriers to workers organising, bargaining, taking action and having their say. Union density took a hit; bosses were ascendant.

And, as labour specialist Professor John Buchanan reminds us, despite productivity doubling over this period, 10% of GDP shifted from workers’ pockets to the pockets of employers and investors.

At the same time as union solidarity was being attacked, so too was the capacity of civil society to organise and advocate. Bearing witness and speaking out became seen by political leaders as treason rather than civic duty.

Everybody’s talkin’ at me

4. Responsibility internalised

Personal effort and merit became the new gospels. People became responsible for themselves. The personal replaced the systemic. Fault replaced chance. Social issues become a family’s own dilemma. People were partitioned; issues individualised. What happened to society?

According to Margaret Thatcher, it didn’t exist. It was all about the individual:

“I think we have gone through a period when too many children and people have been given to understand “I have a problem, it is the Government’s job to cope with it!” or “I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!” “I am homeless, the Government must house me!” and so they are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing!”

Life was no longer a shared endeavour but a lonely solo crossing. Fundamental issues of distribution were personalised and, in so doing, de-politicised.

Everybody’s talkin’ at me

5. Society ‘disappeared’

Image: Flickr

The ultimate loss of humanity must be the loss of community and that was central to neoliberalism’s DNA. Possibly the best (and sobering) illustration of this is the response of Alan Greenspan (the then Chair of the US Federal Reserve) to a question in 2007 about which candidate he supported for the US presidency: “We are fortunate that, thanks to globalization, policy decisions in the US have been largely replaced by global market forces. National security aside, it hardly makes any difference who will be the next president. The world is governed by market forces.” ((Streeck, Wolfgang, Buying Time—the delayed crisis of democratic capitalism, Verso, London, 2014, p85.))

Everybody’s talkin’ at me

It is not surprising that Robert Reich’s latest book, aptly titled “Saving Capitalism”, ends by asserting that the critical debate for the future is not about technology or economics or even the size of government but about democracy itself: “about who government is for.” ((Reich, Robert B., Saving Capitalism—for the many, not the few, Vintage Books, NY, 2015 p.219.))

Transformational opportunity

And so, we enter our next pivot point, at the vortex of three wicked problems playing out:

- growing inequality impacting social cohesion and democratic controls;

- automation creating challenges to how we work, live and play; and

- climate change forcing a radical refit of our energy, transport, production and consumption systems and practices whilst responding to ever increasing climate crises and their impacts.

If ever we needed an effective democracy it is now!

Left to market forces alone, some will do very well from this disrupted new world, but most won’t.

I can’t see their faces

Only the shadows of their eyes

This paper takes the second of these issues—automation—to consider both democracy’s role in responding to its challenges and to a consideration of some specific responses, like a Universal Basic Income and shorter paid working hours.

Ideally, we need active government engagement to lead the discussion about the future—about the threats and opportunities automation presents.

We need:

- Rules for how these changes can work—with the interests of people and planet central;

- Governments prepared to confront capital to argue in the interest of their citizens; and

- A new social compact—and what better way for a democracy alienated from many of its citizens to engage, to listen and learn, to debate and ultimately to lead on a plan for the future.

This is a critical pivot point for democracy—it can remain the friend of business and leave its citizens to battle on or it can refocus on its purpose:

- Its purpose as a social democracy not just a nation state,

- Its purpose to limit and civilise market influences so that people’s collective interests and the planets limits are respected and adhered to.

I’m goin’ where the sun keeps shinin’

Through the pourin’ rain

Goin’ where the weather suits my clothes

The second question, then, is capability.

Even assuming the political will exists, is there the capacity to push capital back into its box? Particularly given:

- the global nature of big corporations;

- governments’ reliance (particularly at times of high debt) on capital markets and the threat of capital flight or capital strike; and

- the weakened state of countervailing forces like the labour movement and other forms of civil organisation.

Herein lie some pretty big challenges.

But a community facing a radical assault on their lives and livelihoods, given the opportunity and support to rediscover their agency, could do so to great effect.

![ACTU Your Rights at Work protest, 2005. By Tirin at en.wikipedia (Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], from Wikimedia Commons](https://greenagenda.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/ACTU_protest_20051115-300x200.jpg)

By Tirin at en.wikipedia (Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.) [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0 from Wikimedia Commons

Never underestimate our community’s capacity to care—particularly about the next generation. YourRights@Work in 2007 was a seminal lesson for me. Yes, many workers and their communities galvanised around a message of rights and solidarity, but the most compelling voice was in support of young workers. The community wanted protections for young workers, but they wanted life chances for them too—the opportunity that many older workers had had to buy a home, raise a family, retire with some security all because they’d had a decent job and benefits.

It’s the story underpinning much of Australia’s prosperity—this ‘wage earner welfare state’ where decent jobs, delivered through a regulatory framework, minimum wage-setting and union organisation combined with the social wage and social security system to deliver a decent life. Core to this mix was a decent job.

So a threat from automation to paid employment is a pretty huge issue!

Certainties in an uncertain world

The automation discussion tends to polarise people.

There’s the camp that says paid employment is on its way out—and within that camp there are those that celebrate that and others that decry it.

Then there are those that argue it’s too unknown to conjecture. They tend to be the same people who tell us not to worry, that these disruptions have some inbuilt equilibrium that will sort itself out … eventually.

Everybody’s talkin’ at me

I don’t hear a word their sayin’

Only the echoes of my mind

… a threat from automation to paid employment is a pretty huge issue!

This latter view is particularly insidious as it:

- denies people’s justified concerns;

- provides false comfort because, even if new jobs come, there will be a deep and painful transition potentially resulting in a whole lost generation or two; and

- denies people any agency to engage early to shape these new changes.

But it is true that there are a lot of unknowns when it comes to this debate. So, what do we know?

1. Moving from muscle to mind

As one typology explains we’ve had three phases of automation: ((Davenport, Thomas H, and Julia Kirby, “Beyond Automation”, Harvard Business Review, June 2015.))

- The 19th century saw automation replace the dirty and dangerous;

- The 20th century replaced the dull; and

- The 21st century will replace decisions

It is this transition from muscle to mind replacement that makes this technological change so impactful. There are a number of studies now available on the likely impacts, and CEDA’s recent Australian study is consistent with these. CEDA estimates at least 40% of existing paid work have a ‘high probability’ of replacement in the next 10–15 years.

2. Automation is both an accelerant and accelerating

We know the rate of change is accelerating—and its pathway is exponential rather than linear. While regulators try to deal with Uber drivers, Uber is already trialling driverless cars.

3. Workerless business models on the rise

The new business models that technology enables are also very different: they’re predicated on mass reach —preferably via monopoly positioning; they are essentially worker-less; ((Stern, Andy with Lee Kravitz, Raising the Floor—how a universal basic income can renew our economy and rebuild the American Dream, Public Affairs, NY, 2016 p.66–7.)) and they provide a platform for others to transact and/or interact. Experience to date also suggests that these mega businesses will attract the investment dollar over plant-and-people businesses. These businesses tend to favour tax havens over tax payments. And they already control key parts of the democratic commons. Compare 1990 when the top three carmakers in Detroit had a market capitalisation of $36 billion and 1.2 million employees to 2014 when the top three firms in Silicon Valley, with a market capitalisation of over $1 trillion, had only 137,000 employees. That’s thirty times the value and one tenth the workforce!

4. We don’t do transition well

5. We over-valorise paid work

Paid work has not just become an activity in which many engage—it has come to define a person’s worth. UBI specialist Simon Birnbaum captures well the rhetoric we hear constantly in public narratives:

- always better to have a job than an income;

- any job is better than no job; and

- if not part of ‘productive economy’ mustn’t be productive. ((Birnbaum, Simon, Basic Income Reconsidered—Social Justice, Liberalism and the Demands of Equality, Palgrave Macmillan, NY 2012 p.60.))

It is the propagation of this type of framing that gives political leaders and the media license to demonise and stigmatise people who can’t access work and it reinforces the undervaluing of other important work in the family and society—simply because it isn’t paid.

The CEDA Report indicated a potential 40% job displacement. Let’s say its only half as bad as they suggest —20%. In the ‘best case’ scenario that’s one in five paid jobs gone—and don’t forget, that’s on top of the 16% of Australian workers already unemployed or underemployed.

This is a crisis-in-the-making.

We don’t have a welfare system fit, designed or funded to cope; we don’t have the tax base to respond; and we currently have no political leadership on the issue from governments. Where’s the community conversation about how we shape his change, how we soften the transition, how we lead the fightback for a different type of mixed work-leisure society?

A new social compact?

In “Saving Capitalism”, Reich gives us a timely reminder that we have a choice between a market “organized for broadly based prosperity” or one whose gains reside with the top. Despite nearly forty years of being schooled in the TINA—there-is-no-alternative—principle, Reich reminds us that “The market is a human creation. It is based on rules that human beings designed.”

It’s a timely reminder that people and governments have agency. A workless future is not immutable. Technology is a tool and it can be shaped or responsive to different demands or rules. Driverless cars, for example, could reduce car ownership, interacting efficiently with public transport systems to revolutionise city planning, commute times, carbon footprints, quality of life. Alternately, driverless cars could add to cars on the road, their cheaper economics could undermine investment in public transport systems and so make city living that much more polluting and unliveable.

It’s important we talk about what’s coming and shape the guiding principles for the change we want to see—for the world that focusses on people and planet first.

Two propositions that could be part of a New Social Compact, that particularly respond to the impact of automation on paid employment, are shorter hours and a UBI.

1. Work less rather than workless

Keynes foresaw dramatic reductions in paid working hours as a sign of great societal advancement. He projected that the standard of living of the western world would multiply at least four times between 1930 and 2030, by which time people would be working just 15 hours a week. He is partly right—by 2000, countries like the UK and US were already five times as wealthy as in 1930.

Keynes saw increased leisure as a ‘prosperity dividend’. Counterpoise that with the question Juliet Schor poses: “Why has leisure been such a conspicuous casualty of prosperity?” ((Gini, Al, The Importance of Being Lazy—In praise of play, leisure and vacations, Routledge, NY, 2005 p.83.))

One of the earliest organising victories of the Australian union movement, with societal reverberations, was the winning of the eight-hour day in the mid-1850s. Importantly, it was framed in the context of eight hours work, eight hours sleep and eight hours recreation.

One hundred and sixty years on, how has our increased wealth translated into paid working hours and a better balancing of life?

In Australia, we now have a very gendered and bifurcated labour market:

- five million Australians, mainly men, work more than 40 hours per week;

- 40% of female workers work part time hours; and

- 16% of workers are underemployed or unemployed.

Assuming automation will have a big (maybe even massive) impact on paid work, one response would be to look at how paid hours could be more fairly distributed. Even if you a UBI, most people will still want, and need, to engage in some level of paid employment.

In Australia, we now have a very gendered and bifurcated labour market …

There are a range of ways to curtail hours:

- Cap maximum hours—although this would disproportionally impact male workers as they currently work longer hours;

- Have a more flexible approach to shorter hours—but this is more likely to increase wage inequality as it likely favours highly skilled and senior positions;

- Cut the number of working days in a week. Utah recently trialled a four-day week for government workers and, although the trial has since ended, it was liked by the workers and had appreciable and varied impacts from lowering the carbon footprint and reducing commute times to improving health outcomes for the workers involved; or

- Cut the hours worked per day. Sweden is trialling six-hour shifts in a few places. Early indications are that, like the Canadian Mincome trial of the 1970s, improved health and reduced use of medical services is a noted feature of the trial to date.

It’s premature without a lot more analysis and debate to jump to conclusions on best ways forward. Clearly there are no easy solutions!

But what we can say is:

- This is a political issue—not simply the problem of individual workers trying to navigate a new labour market;

- It is, and should be treated as, a sharp distributional point of conflict which will have fundamental impacts on equity and power in this country; and

- It shouldn’t be left ‘to the market to decide’

Everybody’s talkin’ at me

I don’t hear a word their sayin’

Only the echoes of my mind

2. A Universal Basic Income

A UBI can be all things to all people.

For the libertarian right it’s a dream come true—a single payment that extinguishes the welfare state. The ultimate marketisation of life—people use their voucher to buy insurance if they want to guard against unemployment or old age, purchase education or healthcare or whatever they choose to prioritise (assuming they can afford market prices). This view also calls for the eradication of labour regulation— particularly the setting of minimum wages and standards.

This is not a model of UBI conducive to a more equal and more cohesive society. But there is something compelling about the UBI—from both a rights and democratic perspective.

UBI as a right

![Activists from Generation Grundeinkommen organise a performance in Bern, Switzerland in support of a basic income. By Stefan Bohrer [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://greenagenda.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Basic_Income_Performance_in_Bern_Oct_2013-300x200.jpg)

However, how that right is expressed will be critical. In a world where paid work is likely to be reduced, people’s reliance on the UBI for basic economic security will be essential—if not sufficient. The ability of governments to ‘play with’ the payment needs to be safeguarded against. Ensuring the basis for the right is guaranteed, e.g. in the constitution, needs to be explored further.

UBI and democracy at work

UBI has the potential to assist with both a re-purposing of democracy and a reorganisation of civic engagement.

Its very existence—a substantive and ongoing redistribution of income—will create sharp conflict between implementing governments and capital. Funding a ‘reasonable rate’ will require new and increased taxes from those capable of paying more. But herein also lies its weakness: reining in global corporations, regulating against tax havens, and reversing the downward trend in tax rates for corporations and the mega wealthy, will be challenging for single nation states. New demands for global interventions and regulation will need a lot more thought.

But government need not fight the battle alone, and indeed can’t win if they do so.

UBI creates a form of ‘community wage setting’. In any bargain over wages, people need to be organised to win and protect a fair share. So, whilst UBI has many dangers for organised labour (built largely around a workplace based bargaining model) and current civil society organisations (many of whom exist within the current welfare state model), it could be the source of new community engagement and organising.

There will certainly be a lot at stake!

There are also pragmatic issues whose resolution will be key to whether UBI is both workable and acceptable. We should not rush to embrace or dismiss UBI without the exploration of these pre-conditions, parameters, safeguards or rules. At this early stage of the debate, a few matters jump out:

Quantum matters

The level at which a UBI is set will determine whether it’s just another supplementary payment or a real subsistence income.

Special need matters

Although the UBI could replace much of the current social security system, there would still be services (like job seeking support) and payments (like special disability support) that would need to continue.

Minimas matter

Regulation of the paid wage sector would still be required—particularly the level of the minimum wage. This will be the effective benchmark against which the UBI quantum is set, so it’s critical to maintain its value.

A primitive type of UBI, known as the Speenhamland System, was trialled back in 1800s England when the local magistrates decided to give peasants a basic stipend to top up their wages. Unfortunately, the absence of wage regulation simply meant employers dropped wages and ultimately the stipend was abandoned because it was driving people further into poverty. No regulated wages floor, in the context of a large ‘reserve army’ of people looking for paid work, would see the same outcome repeated 200 years on.

Employment matters

A UBI shouldn’t mean we give up on paid employment. It would still be incumbent on governments and key institutions (like the Reserve Bank, Fair Work Australia etc.) to prioritise employment in their objectives and policy directions. UBI will only be a base—not even close to the current minimum wage on which working people already struggle to make ends meet. Most people will still want or need to look for paid employment.

Portability matters

Given the likely prospect of people working a number of tasks or projects with a multiplicity of employers —rather than a single job with a single employer—new systems will need to provide for the collectivisation of employment entitlements like annual leave and sick leave. Without this, there will not only be a significant diminution in people’s wages but conditions too. That means a big shift in risk and cost to workers, as UBI would basically be a subsidy to employers who no longer were required to provide these types of entitlement. New thinking about portability schemes is required.

Housing matters

Piketty’s analysis of the growing accumulation of, and power of, capital gives us pause in any discussion that envisages a reduction in paid employment and its replacement with a likely lesser UBI. A net reduction in income for many and more precarious work will presumably impact negatively on housing prices, and therefore lead to wealth reductions for many. But it will also be a struggle for those not in the housing market to access loans or be in a position to handle high levels of debt.

When even Ben Bernanke, the former Chair of the US Federal Reserve, was refused a bank loan, what hope will most people have to ever get into the housing market? And this has historically been the route for working people to build a small wealth store and security for their old age. With housing already increasingly beyond the reach of many—particularly younger Australians—this piece of policy needs some radical and innovative thinking.

Retirement matters

Retirement incomes will also need re-thinking. A decrease in paid working time and income will have a big impact on workers’ capacity to build superannuation accounts. What does this mean for retirement incomes and, more broadly, what does a world of reduced work potentially mean for the current increases in retirement age?

Non-citizens matter

In Australia we have nearly one million workers of various visa and non-citizen statuses. They will not be covered by a citizen-linked UBI. What are the protections and regulations required to ensure we don’t create a further sub class?

This list is by no means exhaustive, but it shows how the devil will be in the detail for a UBI. A single unconditional payment to all citizens will not be a silver bullet, but it could be an important buffer against widespread poverty resulting from reduced paid work and a failing welfare state.

Summary

The future is looking increasingly challenging and the solutions complex. This paper has only touched on automation and hasn’t even considered the impacts of climate change or growing inequality. But the question is clear: do we have the leadership and organisation that will enable people to help understand, debate and shape that future?

It could go either way. The form, in recent decades, of social democratic parties—their short-term horizons, capture by market thinking and tendency to follow not lead—justifiably gives us pause. But the scale and nature of the changes coming could also be the catalyst for a re-engaged community that pushes our politics in new directions.

Key to those new directions will be new thinking about how we deal with the impacts of new technology on paid work and how we rethink the precepts of the welfare state. Specific measures like UBI and shorter working hours may well be part of the eventual mix.

But it is ‘how’ we get there rather than ‘the what’ that will be most critical in shaping the future. And, at the heart of ‘the how’ is whether citizens’ stories, fears and ambitions are seen and heard, whether they are part of the debate and part of the shaping. Will it be a mass democratic response or will everyday folk be passed over? Will political failure mean their exclusion and allow capital to write the new playbook? That would surely write the epitaph for social democracy as it was envisaged and sow the seeds for a shift to a more authoritarian politic.

Everybody’s talkin’ at me

I don’t hear a word their sayin’

Only the echoes of my mind

The struggle is to create a new future—a home where people and planet come first:

I’m goin’ where the sun keeps shinin’

Through the pourin’ rain

Goin’ where the weather suits my clothes

Interesting discussion. What’s the difference between the “green institute” -!: the “green agenda”? Totally unrelated?

My main comment comes from your statement “Funding a ‘reasonable rate’ will require new and increased taxes from those capable of paying more”

I’m not sure that’s the right approach.

Instead a company that pays 50 people will need to pay a UBI and personal tax to the government for its 50 people, with a correspondingly lower income. Net equal. Then if the company chooses to automate or off-shore 10 employees they’ll still be paying 50 UBI and tax equivalents.

Hi Greg – thanks for the comment. Green Agenda is project supported by the Green Institute, but with editorial independence.

The interaction between a UBI and the tax system and the implications for business and employment are definitely important issues that would need to be thought through more fully if/when designing a UBI scheme.