The Future Fund, Elbit Systems, and Australia’s Normalisation of War

Australia’s Future Fund has increased its investments in Elbit Systems, Israel’s largest weapons manufacturer, by over 600%. While hiding behind “administrative compliance”, Australian public wealth profits from genocide. Scheherazade Bloul exposes this as the “banality of finance management”, arguing that militarisation has become our normalised condition, connecting the Future Fund’s moral bankruptcy to the country’s foundational economy of genocide and empire.

A day after the second anniversary of a 21st-century colonial genocide, officials at Senate Estimates defending the investment decisions laid bare the moral bankruptcy at the heart of Australia’s sovereign wealth fund. The Future Fund, custodian of over $300 billion of public wealth, sees no ethical contradiction in investing millions in Elbit Systems—Israel’s largest weapons manufacturer—whose drones, artillery systems, and AI-guided munitions are central to Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza.

When Greens senators Barbara Pocock and David Shoebridge pressed officials to explain, the Fund’s representatives retreated behind procedure: its exclusions, they said, are based solely on “Australian and US sanctions regimes”. Since neither government has sanctioned Elbit, the Fund claims it is complying with “the rules”. This is despite the findings of the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry, which state unequivocally that Israel has and is continuing to commit genocide in Gaza.

But the dispassionate technocratic answers collapse under the merest scrutiny. The Fund has acted on legal, moral and reputational grounds before. It simply chooses not to now—revealing a political alignment within a profit-directed militarised political consensus with a smirk on the faces of those making and enacting these decisions.

This is also a story of the continuity of militarism and penalism as a structuring force and logic of Australian society.

Elbit Systems: Banned Elsewhere, Bankrolled Here

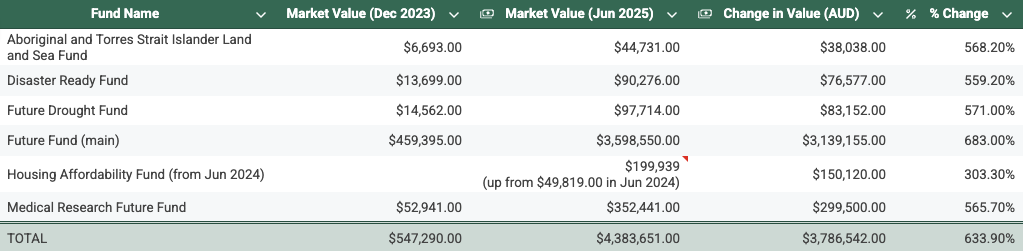

Source: Future Fund periodic statements 2023, 2025.

Elbit Systems has been blacklisted or divested by major funds across the world:

- Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund (the world’s largest) excluded Elbit in 2009 for its role in building surveillance infrastructure for the West Bank separation wall. It also divested from 11 Israeli companies in August 2025 and is reviewing more.

- Denmark’s largest pension fund, KLP, divested in 2010, 2021, and other companies recently. They detail their exclusion assessments comprehensively and transparently in a 17-page document.

- New Zealand’s Super Fund divested in 2012.

Australia, meanwhile, is still pouring public money into war crime-implicated companies despite briefly banning the company in 2022 based on the acquisition of IMI who produced cluster munitions. Freedom-of-information documents show that in late 2023, the Future Fund reversed its earlier exclusion of Elbit Systems, citing updated research from “expert third-party providers” – whoever they are.

Since then, the Fund’s total holdings in Elbit (across all of its funds) have soared by 633 percent, from $597,000 in December 2023 to more than $4.38 million by mid-2025 — as Elbit’s share price surged on the back of Israel’s war in Gaza.

In other words, our “sovereign” wealth fund made a profit while Gaza has suffered (un)told horrors of a genocide over the past two years. This is not a distant tragedy but a direct entanglement where Australia’s public wealth is materially bound to the weapons and technologies that made such devastation possible. As families return to some parts of Gaza, it is with heavy hearts, as entire families were erased from the civil registry, some still buried under the rubble of the destruction of Gaza’s civilian and cultural infrastructure. This destruction is caused by the very companies the Future Fund is a shareholder of.

The Legal and Reputational: A Double Standard in Divestment

In May 2024, under pressure from a Liberal Party campaign led by Senator James Paterson, the Future Fund swiftly divested from 11 Chinese companies accused of links to the People’s Liberation Army or human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Among them were solar giants LONGi and Jiangsu GoodWe, as well as Tsingtao Brewery, whose offence was sourcing hops from Xinjiang Province, which, of course, hosts the internment camps of the subjugated Uyghur Muslim minority. This selective invocation of human rights has been a central instrument in Western geopolitical discourse (e.g. women’s rights to legitimise the invasion of Afghanistan). Scholars describe such machinations as the racialised moral ordering of global politics, where the suffering of some is instrumentalised to legitimise confrontation, for example, with China.

In November 2023, Senator Paterson crowed that taxpayer funds should not be invested in companies complicit in the oppression of minorities, “no action is not an option because it’s intolerable and unacceptable”. And the Fund listened. Before the next reporting period, the Board approved the divestment, despite no Australian or US sanctions requiring them to do so.

So much for only acting when “sanctions apply”.

Moral hierarchies: Militarisation and wealth mandates

As the world watches a Trump-led ceasefire ‘deal’ usher in a new era of colonial administration for the people of Gaza and Palestine, so too does it watch (and partakes in) the capitalist-fuelled, US-led (re)militarisation of the West and allied states. This new era is marked by a form of venture capital militarism driven by speculative investment, technological fetishism, and complicity of aligned states. The banner of ‘innovative’ dual-use technologies — from high-tech cyber capabilities and autonomous systems to surveillance infrastructure and AI-driven warfare — recasts war-making as an engine of economic and industrial growth, with Silicon Valley, for instance, now awash in defence contracts and venture capital tied to the military-tech complex.

Such industrial normalisation of militarism needs capital investment to generate profits (sales through war-making, militarised borders), making militarism a ‘sound investment choice’. Such wording sanitises (beyond humanity) a market logic responsible for the killing, maiming, and violent forced subjugation of people, whether in war zones or in the corridors that those wars and displacements produce, and increasingly, climate-collapsed regions of the world. The geography of this profit is mapped along a racialised global taxonomy where the suffering that fuels the military economy is overwhelmingly borne by those in the places known as the Global South(s)- the very region now rendered uninhabitable by the same extractive and militarised systems that sustain these profits.

The Future Fund’s own Investment Mandate makes clear that its duty to “maximise returns” applies only where such action remains consistent with the Future Fund Act and the Government’s investment directions. In practice, the Fund treats profit maximisation as an absolute, subordinating both legal and ethical obligations to the market’s logic of risk and return. So, a fund whose initial investment capital was generated through the privatisation of public assets like Telstra now funnels this public wealth into companies manufacturing weapons used in genocidal violence. In doing so, the Future Fund transforms the state’s fiduciary duty into a mechanism of neoliberal moral bankruptcy, where financial performance and the linked bonuses outweigh considerations of law, reputation, and humanity.

Australia’s alliances (AUKUS, Five Eyes) sediment the Commonwealth’s belonging to the Anglosphere: that enduring network of Anglophone (and mostly) settler states (USA, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and the UK) that share language, capital, and a myth of civilisational virtue.

The Future Fund’s portfolio and investment decisions mirror this order’s questionable moral hierarchies.

Militarisation as Economic common-sense? Banality of finance and war

The Fund’s refusal to divest from Elbit Systems reveals how militarisation has been normalised as a condition of prosperity. Finance capital has long supported the military, through what has been dubbed the military-industrial complex (a term, ironically, coined by US president Dwight Eisenhower in his 1961 farewell address).

According to the United Nations Human Rights Council report (A/HRC/59/23, 2025):

“Since 2023, Elbit Systems has cooperated closely on Israeli military operations, embedding key staff in the Ministry of Defense, and was awarded the 2024 Israeli Defense Prize. Elbit Systems and Israel Aerospace Industries provide a critical domestic supply of weaponry, and reinforce Israeli military alliances through arms exports and joint development of military technology.”

— Independent International Commission of Inquiry, A/HRC/59/23

The UN report cites multiple sources confirming that Elbit is not merely a contractor — it is an integral part of Israel’s war-fighting infrastructure. Elbit is the main supplier of drones to the Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF/IDF). As Reuters note, in January 2025, Israel signed new deals with the company to produce bombs domestically as part of its intensified assault on Gaza.

So when the Future Fund says it can’t exclude Elbit because it isn’t under “sanction”, it is admitting that its policy prioritises geopolitical alignment over its previously stated human rights’ frameworks.

Banality of administrative violence

The explanation was delivered all with the bureaucratic serenity of arrogant men who mistake administrative neutrality for moral integrity. It is, in essence, the logic of atrocity rendered permissible through the grammar of administrative compliance.

When Senator David Shoebridge questioned the Fund’s interpretation of its exclusion criteria, the exchange descended into absurdity:

Will Hetherton, Future Fund manager of corporate affairs: “The board’s policy is to focus the exclusions process on the conventions and treaties the Australian government has ratified”.

Senator Shoebridge: One of which is the Genocide Convention, and we’re meant to do everything we possibly can to prevent genocide— either from occurring or, if one is happening, from continuing. You understand that’s a key part of the genocide convention?

Will Hetherton: I’m not close enough to provide a comment on that particular answer, Senator.

What unfolds here, in this pathetic answer is not only incompetence, but is in fact revealing of the moral vacuity of the men whose task it is to manage public wealth on behalf of the country’s citizens. They display neither knowledge of the law nor the regulations they invoke, nor the ethical or moral integrity and imagination that administering public funds demands.

In 1963, Hannah Arendt was one of the first theorists to discuss what she termed the “banality of evil” in her essay Eichmann in Jerusalem, after witnessing the post-Holocaust trials of German officers and administrators who took part in the genocide of her people.

As Palestinian scholar Haidar Eid points out, in Palestine today, this banality is not a historical anomaly of Nazi Germany but an ongoing global condition that has disavowed Gaza during the past 17 years of siege and 78 years of ongoing Nakba.

“Because the 2008 bloodbath committed by apartheid Israel was not taken seriously by the UN, the UN Security Council, the European Union, and the Arab and Muslim worlds, the besieging and slaughter of the Palestinians of Gaza in a concentration camp became “normal”, or as Arendt would call it, “banal”.

What we face here, in the Australian context, however, is the banality of finance management. So procedural that atrocities become disavowed and neutralised, far separated from the death and destruction these decisions cause. In such a rationalised process, where genocide is not denied, but simply disclaimed as someone else’s responsibility, the chief corporate affairs officer, Will Hetherton, maintains innocence and compliance through his explanation that the Fund relies on “expert researchers” to provide it with the evidence to invest or not. This rationalisation strips decision-making of any moral duty. The Future Fund to date has quadrupled its initial investment in Israel’s Elbit Systems. But in addition, the Fund holds over $600 million worth of shares in global weapons companies such as Lockheed Martin, Northrup Grumman, RTX.

The Moral Frontier

In 2013, the Future Fund’s Board of Guardians — under then-Chair David Gonski — announced that it would exclude all tobacco producers from the portfolio, justifying the decision on ethical and public health grounds:

“including its damaging health effects, addictive properties and the fact there is no safe level of consumption [make] it … appropriate to exclude primary tobacco product manufacturers,” — Gonski said in Future Fund media release, 28 Feb 2013

If we return to the present, in fact, during the Senate Estimates, Senator Don Farrell, Minister for Trade and Tourism, was explicit about where the moral line lies: “the government supports the decision of the Future Fund not to invest in tobacco products”.

Senator Barbara Pocock: “But you have no position in relation to Elbit’s investment in products that have resulted in the deaths of Australian citizens, an aid worker?”

Pocock’s question should have received a proper response. Yet, the response offered by Minister Farrell was a dismissive “Look, we don’t want any deaths”. Farrell then proceeded to accuse the Greens of wanting to continue the war in Gaza, admonishing Pocock for even asking questions about investments in Elbit Systems, a day after October 7.

The Minister’s evasions and accusations suggest, if I were to analyse his statements in light of the critical framework I have thus far presented, a defensive reflex of the settler and imperial-aligned state. For the latter, demands for accountability are recast as subversion. It is the symptom of a political culture so entangled within a hierarchy of race, that Minister Farrell and those around him cannot name nor see the humanity of Palestinians. Yet it now profits from weapons unleashed on civilian populations. The distinction exposes the hollowness of this morality: harm is only recognised when it is applied to certain normalised or acceptable “bad causes” of death, when it is marketable to condemn.

Militarism, on the other hand, now emerges as the new national brand. It is what ties Australia to past and present empire, justifies endless defence spending, and defines whose deaths count as tragic and whose as necessary.

Australia’s militarised political economy

Rather than lament a neutral law-abiding or rosy past, we should see such banality as a mirror to the Australia that still operates as a penal colony within the Anglosphere empire.

The penal colony at Sydney Cove was (and continues to be) a military occupation of Gadigal lands; the First Fleet was a naval deployment; settlements were fortified, and its convicts were the downtrodden who became foot soldiers of British imperialism on this continent. In this sense, Australia’s first economy was an originary economy of genocide: land acquisition through frontier warfare, massacres, rape, pillage, extraction, and forced-labour discipline built upon surveillance, imprisonment, and death.

Divestment is an obvious step, albeit a radical one, given the military/social bond that has defined the 237-year Australian polity.

To demand that the Future Fund divest from Elbit Systems is not a call for moral purity. It means asking: what kind of future are we funding, and for whom?

The task is not just to divest from one weapons company, but to dismantle the military-financial complex that binds us as agents of empire here and there, entangling us in unspeakable horrors, like the foot soldiers of the 18th and 19th centuries.

As long as we fail to confront that continuity and banality, there will be no just future — only more militarised ones.

* * *

Scheherazade Bloul is a research fellow at Deakin University, where she works on the intersection of digital technologies, power, and imperialism. Beyond academia, she is part of various campaigns and works in community radio, building spaces that speak back. She is a daughter of North Africa living in diaspora on Wurundjeri lands, moving in between worlds with cats always close by.

Feature image: Screenshot from Australian Senate Finance and Public Administration Public Legislation Committee hearings on 8 October 2025. Courtesy of Scheherazade Bloul.