In Sarawak, eucalyptus plantations are replacing biodiverse forests under the guise of “reforestation”. Indigenous communities fight to protect their lands while Australia continues to import timber grown on stolen territories.

When I think back to the Black Summer of 2019-2020, I remember tinderbox bushland hit with infernal heat, eucalyptus trees detonating like poorly designed pyrotechnics, and a billion animals with no evacuation plan for hellfire. The fires were so enormous they created their own weather systems, teaching us new words like ‘megafire’ and ‘firenado’. It was a terrifying, ‘unprecedented’ start to 2020, a word that soon wore itself out under the weight of that year’s chaos.

Then last month in another precedent-setting event, celebrities and everyday mortals alike watched, dumbfounded, as their homes were reduced to ash in Los Angeles. While the notorious Santa Ana winds played the role of lead arsonist, eucalyptus trees scattered throughout the Pacific Palisades acted as willing accomplices.

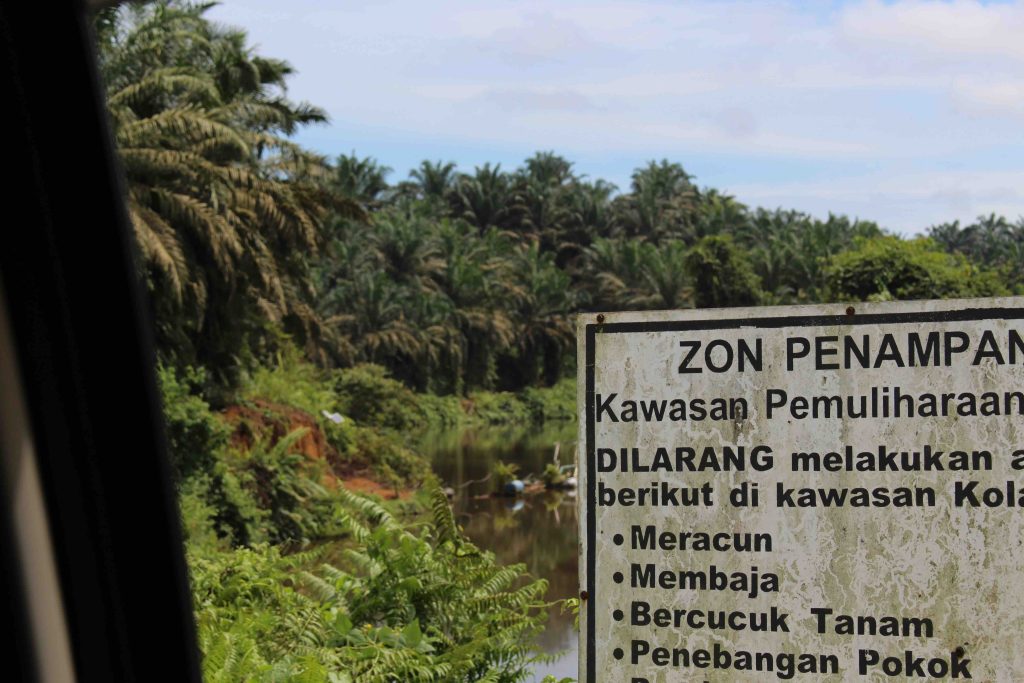

A recently converted forest area in Sarawak

In Sarawak, the last thing you want is a home among the gum trees

This is why, as I drive through endless rows of eucalyptus plantations in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, I am filled with a sense of dread. These trees tap water from the ground like they’ve never heard of drought and have combustible oil filled leaves. Equatorial Sarawak rarely has a daily maximum temperature below scorching, and while its abundant tropical moisture protects its forests from the catastrophic fires we see in Australia or California, I can’t help but wonder: What kind of future does eucalyptus monoculture bring to this environment? And at what cost?

This is a question Sarawak’s remote Indigenous communities on the ground are grappling with too, as industrial timber plantations pose the latest — and arguably greatest — threat to their forests. After decades of fending off loggers, the Kenyah, Kayan, Penan and many other Indigenous forest-reliant ethnic groups are now facing two major threats to their land rolling in under the guise of the green revolution: carbon projects and industrial timber plantations. These plantations are designed to produce fast cheap timber, and are more often than not composed of non-native species like eucalyptus and acacia. The Sarawak state government has grand ambitions to establish one million hectares of tree plantations by the end of this year but has only managed to carve out half so far. Where the rest of this land will be found remains a mystery.

Sarawak’s enthusiasm for plantations and carbon projects makes sense from an economic perspective. Potential carbon offset projects offer lucrative funding from international markets, while timber plantations serve the demands of a globalised economy hooked on cheap construction materials. These incentives create a veneer of climate action while masking the deep ecological damage inflicted on one of the most biodiverse regions in the world. Sarawak’s first carbon offsetting and carbon credit schemes are being pitched to sceptical communities as we speak, touted by the same logging companies these communities have been batting away for years like so many unwelcome flies. Shing Yang and Samling are two of the major players, neither of which have glowing reputations on the ground.

The village we are visiting stands in stark contrast to the plantations we’ve driven through. Punan Bah sits on the mighty Rejang River, its edges hemmed with misty, otherworldly forest. Birds flit through the canopy, while mighty durian trees — planted by the community generations ago — tower proudly above their neighbors. Apart from the mobile phones and power lines, the village looks much as it would have when Australian soldiers floated through in 1945.

Punan Bah on the Rejang River, Sarawak

Enthusiasm for plantations here is notably absent. Unlike selective logging — which, when done right, spares smaller plants and trees — plantations hit the reset button on the landscape, clearing everything in their path. Medicinal plants, fruit trees, rattan, and the multitude of other resources local communities rely on vanish under this scorched-earth approach. What remains isn’t a forest; it’s a monoculture — a sterile, flammable shadow of what once was.

At home in Naarm/Melbourne, palm oil’s environmental sins are common knowledge at any dinner party. Yet almost no one knows about the threats posed by industrial plantation timber. While we applaud ourselves for preserving our own old-growth forests, we are unknowingly propping up industries that erase the forests of our neighbours. Malaysia is Australia’s fourth-largest supplier of wood products, representing $192 million AUD in 2023. Timber from Sarawak accounted for $7.7 million AUD, approximately 4% of this figure. Australia is the top importer of plywood, fibreboard and veneer from Sarawak outside of Asia and the Middle East. Despite its shiny new timber regulations, Australia does nothing to protect against the import of timber grown on stolen Indigenous lands. Australian consumers continue to buy plantation timber from tropical countries, thinking they are doing the green and responsible thing.

Looking out from Punan Bah at the remaining native forests

As we walk through the Lana Plantation’s ‘Reforestation’ sites, our host Gebril Atong gestures at the land around us. ‘This was all my childhood playground,’ he says, his voice tinged with both pride and sadness. Gebril speaks from hard-won experience — he once worked for the plantations in this area and knows their reality too well. The forests around Punan Bah have been spared only due to fierce community campaigning and a decade-long legal battle that remains unresolved.

We fly our drone to inspect the scabby plantation landscape and see the various iterations of the industrial timber lifecycle. Gebril points out where trees are planted along the riverbank, in violation of riparian buffer rules. He shows us where fire has been used to clear land, against open fire regulations. He shows us where trees have been planted on steep hills, breaking the 25-degree limit. It’s a buffet of rule-breaking as far as the eye can see.

The Lana Reforestation site, where 60 square kilometres of natural forest has been earmarked to be converted into industrial timber.

These plantations, Gebril points out, have been repackaged as ‘planted forests’ — a label that allows hundreds of thousands of hectares of land cleared for industrial timber to count toward Malaysia’s official forest cover numbers. This lets Malaysia announce to the world that it’s lost no annual forest cover, winning international praise, while old-growth ecosystems are systematically transformed.

‘They just cover it with something that can please people outside Malaysia,’ Gebril explains. ‘Deforestation becomes reforestation. Monoculture is now silviculture. That’s how they manipulate buyers, by confusing them. The words on the page change, but the practices are exactly the same.’

Gebril watches as an excavator harvests industrial timber at the Lana site

NGOs in Sarawak are working hard to challenge this narrative. RimbaWatch, Malaysia’s only climate watchdog, has repeatedly pointed out that Malaysia is scheduled to lose just over 3 million hectares of natural forest under current approved licenses. The official numbers say Malaysia won’t lose any, because the state counts oil palm plantations and industrial timber as forest.

Using this clever bit of forest accounting, deforestation for palm oil is alive and well in Sarawak. We watched throughout 2024 as, month after month, the forests around Long Urun in the Upper Belaga river disappeared from the satellite. The community is losing its temuda, the native customary farmlands, for new oil palm plantations — something that is supposedly no longer happening in Malaysia. Fed up, the village finally set up a blockade in December as a last resort to stop work.

At The Borneo Project we keep a close eye on the satellite, and try to verify what is happening on the ground whenever possible. When we see big smudges of pink or purple across the satellite image on Global Forest Watch — signalling that there has been deforestation or a vegetation disturbance — we try to visit the area. When we can reach the villages, we are generally met warmly, with food and drinks, often a place to stay. Invariably, there is an unsettling story to tell. Over the last year, we’ve heard stories of Shin Yang docking pay from a worker for the hospital bill when they crushed their arm at work. We have heard about Samling destroying a salt lick, a precious resource for the many threatened animals that call these forests home. We’ve been turned back on the road, told that the logging company built and therefore owns that road, unable to verify a huge area of lost forest in the Upper Belaga region.

Another local group SAVE Rivers Network and Sahabat Alam Malaysia (Friends of the Earth Malaysia) have been visiting communities to educate them about the carbon market, to share the less-than-awesome outcomes of similar projects around the world and to hear firsthand what villagers have been told. What they’ve seen in similar projects elsewhere, is Indigenous communities taken advantage of, and left further disempowered.

In the case of the Jalin carbon project, also in Sarawak, the community was informed that they would no longer be able to use forest resources within the project area. It’s a restriction that stings deeply, denying people the very tools of their survival. As Mutang Tuo from Long Iman, a Penan village in the area explained, ‘They said, the purpose is that our forest will have more wood and make the air more fresh. How is this going to happen? We Penan people are no longer allowed to enter the forest and are no longer allowed to cut wood, hunt and collect forest products. How could we not enter the forest, while we depend on the forest to live?’

Gebril Atong welcoming us as we enter Punan Bah by footbridge

For communities like these, hunting and gathering aren’t just survival tactics, they are tied to rituals, storytelling, and knowledge passed down through the generations. Taking away access to forests doesn’t just disrupt daily life; it severs a lifeline to heritage. ‘What people don’t realise, is it’s not just about land grabbing,’ Gebril explains. ‘If you take away our land you take away our identity. Without forests, we can’t teach children words for plants, trees, animals, everything else. It all disappears, our whole culture.’

The Kenyah and Penan communities we work with in the Baram have launched agroforestry projects and tree nurseries, and are keen to do reforestation work in degraded areas. Their dedication is unwavering, their vision clear: to build livelihoods that regenerate rather than deplete the land. The only missing piece is funding. If even a fraction of the climate finance funneled into dubious carbon schemes were instead directed to these frontline communities, the impact would be profound — not just for them, but for the future of our planet.

The remaining forests outside of national parks are still there because of hard won fights led by remote Indigenous communities on the ground. We need these communities to win, not just because it’s the morally right thing to do (though it absolutely is). Their battles are frontline defenses for everyone. While they’re erecting blockades and putting their bodies in front of bulldozers to safeguard their culture and livelihoods, the benefits ripple out globally. We’re all in this flaming mess together.

Climate calamities like floods and droughts — and indeed megafires — might seem ‘unprecedented,’ but they’re not unforeseeable in a world skating past its climate tipping points. Tropical forests, so often called the planet’s lungs, are irreplaceable sentinels of stability. To swap them for plantation monocultures is the difference between taking a deep, nourishing breath and relying on an artificial ventilator. Sure, both might technically work — but one leaves us gasping for survival. If this trend of annihilating forests in the name of climate progress continues, the irony will be blistering: our best intentions leaving us literally and figuratively cooked.

Fiona McAlpine is a member of the Borneo Project. The Borneo Project works to protect the forests, livelihoods and cultures of Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo. You can learn more about Fiona and TBP’s work at borneoproject.org and you can support them work at borneoproject.org/ways-to-give. Follow on TikTok @theborneoproject or on Instagram and Facebook @borneoproject

Featured images courtesy of The Borneo Project.

In Sabah, the babi hutan or wild boar almost extinct cause by the plantations of oil palms. Before the population of wild boar decreased the case of crocodile attack to human is low, but now , the case of crocodile attack to human rapidly increased. So we urge government please preserved our forest and increase the population of wild boar.

Hi Tonny, we see the same thing in Sarawak. Last month we saw some babi hutan had returned to the area we work in, years after they were wiped out by swine fever and habitat loss. Fingers crossed they make a come back!

Thanks Fiona for this alarming account of what’s really going on in the forests of Borneo. I’m interested to know whether the wood products from these plantations have been certified as FSC?

Hi Janet, sorry for the slow reply! Here is more about the FSC complaints we’ve made: https://borneoproject.org/fsc-latest-investigation-finds-samling-guilty-of-illegal-logging/

Save plants, trees and even grasses, IF you want to save the world for upcoming generations.

— From New Delhi, India.