Community bike workshops in Australia

While the original formulation of ‘mutual aid’ by Kropotkin was radical and linked to changing political conditions, mutual aid in the voluntary sector of contemporary Australian society cuts across political positions, gender, race, and wealth. In this short article we will recount engagement with a growing movement of bike activists and volunteers who challenge consumerism and automobility in the transition to greener modes of transport, through their work in community bike workshops or bike kitchens. As the Australian bike workshop movement expands slowly, it is demonstrating that low-cost grassroots movements can encourage change, just as much as supply-side interventions like expensive bike lanes and engineering safer streetscapes do. Workshops ‘engineer’ a change in values.

1. What is a community bike workshop?

Community bike workshops (CBWs) or bike kitchens are small organisations, largely located in cities and larger towns, where bicycle repair and maintenance takes place. Unlike bike shops, people can fix their own bikes and learn these skills, while in others, bikes repaired by volunteers are offered freely or cheaply to people who need them. Their major goal is always an extension of the useful life of bicycles and components using second-hand and some new components, and they share many values with other organisations in the community economy, as we will explain. This means they are important, although often unrecognised, players in socioeconomic transitions to lower emissions and healthier mobility options.

CBWs are established by activists and community-minded cyclists, sometimes with limited support by local councils, donors, or non-profit organisations. CBWs are agents in the circular economy. Interrupting the waste stream to re-direct unwanted bikes and components is a worthwhile activity; donated or scavenged bikes are re-used creatively and cheaply with a DIY ethos, avoiding too much new consumption. Some bikes or parts may be sold to support ongoing workshop costs, but rarely for high prices.

Another distinguishing feature is that, unlike bike shops or commercial ventures, they generally have very modest financial turnover, and low or no labour costs. Worldwide, our surveys of over fifty have found the majority operate with a volunteer workforce, although in some countries like France, government employment schemes financially support some paid employees. In most cases, therefore, volunteers want to participate, as part of ‘mutual aid’, finding convivial ways of working together and resolving technical repair problems in a supportive way.

Workshops numbers have grown since the 1990s, and are widespread across Europe and the Americas, and they are found across the rest of the world. The largest concentration is in France, with over 350 of different types. Most of those are networked through l’Heureux Cyclage, which coordinates events, logistics, and learning between workshops, and they assist well over 100,000 people yearly. In Belgium, Brussels has at least 18, like Cycloperativa, spread across the city’s arrondissements. Ten bike workshops operate in Austria, with at least four in Vienna. They include WUK which, established in 1983, is perhaps the world’s oldest.

We want to signal that this movement exists in Australia too, and we will clarify the contributions of workshops to sustainability, self-help and solidarity networks. A new online map of bicycle recyclers across the country maintained by Dr Bart Sbeghen identifies approximately thirty Australian workshops, and this number is growing annually. They are concentrated in Melbourne where we have all volunteered or worked, but extend across other cities.

2. Mutual aid and conviviality in the bike sector

Although, as a practice, mutualism predates anarchism, the first articulations of the concept of mutual aid can be traced back to anarchist thinkers Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Peter Kropotkin. Proudhon proposed “a form of market socialism” based on reciprocity and non-hierarchical collectives similar to what we see in contemporary worker cooperatives (Shannon, 2019, 100). In turn, Russian anarcho-communist Peter Kropotkin in his Mutual Aid, a factor of evolution, (1902) considered the role of mutual aid in the animal world, and in human societies, positing that evolution is driven by mutualism and not by survival of the fittest. Subsequently, however, the concept of mutualism has had, “within the anarchist tradition”, a “long, complex and contentious history” (Wilbur 2019, 213), which is beyond the scope of this article. In any case, mutualism should not be exclusively framed as an anarchist concept, as it has been adopted (and adapted) by movements outside that ideology, as we will show.

More recently, the polymath thinker Ivan Illich claimed that tools had become monopolised in the hands of industrial production and “integrated at the service of a small élite” like never before (1973, 104). In order to develop a more equitable society (including more equitable transport), based on “participatory justice” (p. 29), Illich proposed the use of convivial tools, meaning simple technology -mostly hand tools- easy to use and accessible to everyone. As Linnea Møller Jess points out, Illich saw the bicycle as a form of convivial transport, which can “be autonomously operated and repaired while not constraining the time and space of others” (2023, p. 139). Jess also notes that the “speed-sceptic work of Illich has been translated into contemporary degrowth discourse” (p. 139), specifically in regards to the need for equitable transport. The concept of ‘convivial tools’, she adds, relates to the value of ‘autonomy’, central to degrowth approaches, “…as it refers to technologies that are simple to understand, communally owned and democratically developed based on the active involvement of the users” (p. 139). Enduring simple technologies have a place in a decarbonising world: Puig de la Bellacasa (2017, p. 210) commented that “Foregrounding the importance of care, maintenance, and repair … is a step in challenging teleological progressive shiny ideals of innovation”.

A final term that closes the circle around what workshops do, is the French neologism ‘vélonomie’ (from velo: bicycle + autonomie: autonomy). Clearly linked to the previous concepts, it is sometimes translated as ‘velonomy’ (and should not be confused with ‘velonomics’, which relates to the economics of cycling). Vélonomie refers to “the acquisition of autonomy on a bicycle through the learning of various skills that facilitate cycling” (Abord de Chatillon and Eskernazi, para 2). In a broader sense, vélonomie establishes a link between the bicycle, the cyclist, and, importantly, the social environment in which cyclists move (but also purchase and maintain their bicycles), emphasising the need to be proficient in technical operations (such as learning to change gears or to carry out repairs) but also societal codes (road user interactions, perception of cyclists, etc.) (Abord de Chatillon and Eskernazi, 2022, para 2).

3. Vélonomie and its arrival in Australia

Australia’s long travel distances, even within some towns and cities, and its strong automobile culture have meantvélonomie is lagging. The bike does not rule the Australian roads, and cyclist modal share of transport is probably lower than in the early 20th century (in Melbourne, commonly 1.5%-5% of all trips). But there has been a notable uptake of interest in riding, and learning bike repair skills in recent years. The C-19 pandemic expanded cycling a little, with a temporary increase in bike sales and use, and more and more gig-economy food deliveries are made by bikes and e-bikes in most metropolitan areas. Bicycles tick many boxes: riding is relatively cheap and certainly healthy, and shorter journeys are more rapid than other travel modes. Most repairs on the bikes commonly found in Australia can be done with fairly basic tools.

Contemporary supply-side policies and planning measures have led to the development of cycle lanes and road treatments that are more inviting for novice cyclists. But community bike workshops are about something different: not ‘supplying’ better streetscapes, but increasing demand for cycling. We see this as a key issue for sustainable mobility transitions: encouraging people to adopt cycling as a culturally acceptable and healthy alternative to the car or even to public transport. Community Bike Workshops are one place where vélonomie is nurtured and demand for cycling increased, as part of ‘mutual aid’ and ‘conviviality’.

As many readers will realise, bikes are a healthy and practical alternative for short and medium length journeys in a carbon-constrained world. Bicycles are a relatively simple technology, in some respects a technological dinosaur, having survived since the 1890s because they cost very little to own, store or run and offer exercise as well as transport. We have come to respect and value the bike in an age where reuse, recycling and refurbishment are increasingly important. A quality bike can be repaired, reused and rebirthed many times, as can most components (Nurse 2021, 73; De Decker, 2023). All workshops stock salvaged parts to assist this, although with varying degrees of tidiness and efficiency.

While few households have all the simple tools needed to repair bicycles of the sort that Illich wrote about, CBWs provide them, along with a community of bike-fixers. Workshops are almost all not-for-profit, running on what Zac Furness called “DIY ethics” (Furness 2010: 178) with an aim to assist others, maintain environmental sensitivity, and nurture satisfying friendships and social relationships, all alongside actual bicycle repair, recycling and redistribution.

The history of CBWs in Australia goes back to the 1990s. Positive outcomes for community, equality and the environment mean that today local Australian councils and nonprofits encourage and cooperate with CBWs, realising their value and often assisting with premises or insurance. The Bicycle Garden in Sydney, for example, is co-located with a community centre supported by the City of Sydney, and the workshop fulfils several different functions. Like subsidised public transport, the presence of CBWs is an environmental nudge or lubrication, gradually changing behaviours (Molsher & Townsend, 2016), making donation of unwanted bikes simpler, as well as improving repair skills.

We have observed that learning in CBWs is by and large non-hierarchical, and tends to be reciprocal in nature with volunteers able to pass on their knowledge to others after a few sessions. It helps that there are many skills needed in a workshop from working with customers to book-keeping, delivering, food preparation, parts sorting, cleaning bikes, and all aspects of bike repair.

Generally the larger the bike shed, the better the expertise, range of tools and ability to cope with advanced bike technologies such as hydraulic disc brakes, hub gears and thru-axles. Cheap poorly manufactured bikes, and high-end super-lightweight racing bikes, are less favoured for recycling or reuse. Electric bikes need additional skills to repair and maintain. Workshops may divert these to bike shops, or obtain mutual aid from other volunteers.

| WeCycle, Melbourne: a small example of mutual bicycle aid WeCycle is a small social enterprise fixing and distributing bikes for people in need. It has operated since 2017 in the inner north of Melbourne. The majority of bike recipients are referred by social care agencies who pass on requests for bikes from families and individuals. It operates from a small building owned by the local council, and it is a convivial if slightly chaotic space where disassembled parts, and bikes in progress, are stored. The budget is lean; major costs are insurance and parts that cannot be recycled, like brake pads, grips, chains and cables. These are sometimes paid for by community grants, or by selling a few unwanted bikes at modest prices. All labour is carried out by a diverse group of 4-9 volunteers working once or twice a week. The work is largely ‘convivial’: mutually supportive and helpful, but of course with occasional frustrations that need to be resolved. WeCycle delivers more than 170 bikes a year to households and individuals, many of whom are refugees or asylum seekers. Other Melbourne workshops do similar work, making the combined efforts a substantial contribution to welfare and sustainable transport needs across the city. Connecting recipients with their bikes is sometimes challenging given Melbourne’s large size, and arranging visits with newly arrived migrants who speak little English. Volunteers are assisted by the social care agencies. Anecdotal evidence is that these bikes are used for commuting, school, and leisure, and occasionally returned for servicing. Once a month, WeCycle volunteers also check and sometimes fix bikes for local residents as part of a scheme for the public, with Council support. |

4. Contributions to social transitions and mutual aid

Firstly, we want to stress that Australian workshops have yet to attain the coverage and size of their French or Belgian counterparts. In Margot Abord de Chatillon’s surveys of the repair skills of 451 Melbourne bike riders, she found only 12% had heard of bike workshops (2022) in a city that is moderately bike-friendly. CBWs are what Gibson-Graham call ‘prefiguring’ organisations, ahead of the game and showing what can be done by committed people, but still few in number. We know, after all, that teenagers commonly abandon bikes as they transition to automobility and certain cities, especially where the weather is difficult or the terrain too hilly, have few cyclists and no workshops. Depending on what definitions are used, Tasmania has only one: there are almost none open to the public in Queensland. The newest are the Bicycle Canteen in Wagga Wagga, NSW and the Bike Op Shop, a youth project in the Melbourne suburb of Broadmeadows. In Melbourne, with the most workshops (7-8), we are beginning to close the circular economy for bikes a little, with more diverted away from landfill or liberated from back yards. Of course, as happened with some forms of valuable E-waste, there are limits to supply. Maintaining volunteer numbers is another limitation.

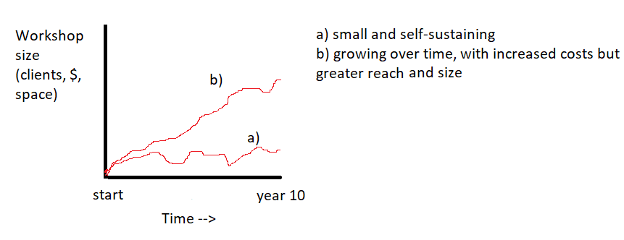

A second issue for enabling societal transition is whether convivial relationships can be maintained in workshops that adopt more commercial practices over time. There are already variations in Melbourne between large and well established workshops and smaller and newer ones. The critical moment is when workshops have employees, paid out of bike sales or grants. Then, workshops can overlap with what bike shops offer, need to change their official status, and have to pay employee benefits and other contributions. This has occurred at the CERES Bike Shed and Back2Bikes, both in Melbourne. Experimentation with modes of functioning are normal, but professionalisation brings financial cost, and a need to maintain income. Other workshops stay small, but can reach far fewer people (Figure 1).

A third concern is vital efforts to counter the male-dominated aspect of bike repair, and of course to respond to the #MeToo movement and diversity initiatives across the country. Abord de Chatillon’s 451-person bike repair survey and interviews with mechanics in Melbourne in 2018 confirmed that repair and maintenance are largely male activities; less than 10% of professional bike mechanics are women (Abord de Chatillon 2022: 371). Actions (largely) by men in bike spaces that workshops need to regulate through codes of conduct and informal training include giving unwanted attention to female clients, making assumptions, and denial of women’s repair expertise. There are examples of socially dysfunctional behaviour. Workshops, just like bike shops, need to be safe and egalitarian across intersectional identities (some workshops in Australia already already provide certain sessions dedicated to women and gender minorities,like ChainLynx at the Bicycle Garden). Agreed codes of conduct need to be made and enforced, with reflexive awareness of gendered behavioural norms and other power inequalities. In addition, in France and Australia, Abord de Chatillon found less affluent riders resort more often to community bike workshops, and also repair their bicycles themselves more often. They more often own bike tools and are more confident at self-repair. Developing and funding more workshops therefore addresses social justice for these groups. In addition, there are additional inequalities if richer urban jurisdictions with more affluent riders are the places where good infrastructure and dedicated cycle lanes are concentrated.

5. Prognosis and conclusions

A major Routledge Companion to Cycling was recently released, and in it the editor Glen Norcliffe highlights that in bicycle cooperatives and collectives like CBWs, “The top-down profit motive of laissez-faire is replaced by sharing, mutual assistance, reciprocity and democratic decision-making.” (Norcliffe 2022, 152). This returns us to Kropotkin’s ideas. Norcliffe’s critical point is that workshops ‘design’ and implement their own regulations and modes of operation, as well as carrying out their convivial repairs. This organisational task is fluid and sometimes messy, as workshops work through their establishment, everyday functioning, and possible growth. Finding and maintaining premises is one main task, fortunately aided in Australia by bike-friendly local councils or non-profits.

While recognising that workshops struggle sometimes because of their marginality in mainstream Australian culture, it is important to stress that community-driven, affordable mobility efforts transitions we describe are largely occurring outside the reach of governments and corporate Australia. They join with repair cafés and youth programs of different types, and the bicycles that anchor them are challenging mainstream, fossil fuel-based urban mobilities (Furness 2010). Workshops ‘engineer’ a change in values with their ‘convivial tools’ used at the grassroots and in a convivial way, just as much as engineers and transport planners engineer our streetscape, cycle lanes, and bike parking. All of them do important work.

CBWs are ‘transitional’ organisations helping to bring about change, but they are locally-based and still small in size and number. The lofty aspirations of ‘mutual aid’ and those supporting a greening of mobility in cities can learn much from them, by engaging with their growing numbers of participants.

References

Abord de Chatillon, M. (2022). Velonomy and material mobilities: Practices of cycle repair and maintenance in Lyon, France, and Melbourne, Australia. PhD thesis, ENTPE, Université de Lyon.

Abord de Chatillon, M. and M. Eskenazi (2022) Devenir cycliste, s’engager en cycliste: Communautés de pratiques et apprentissage de la vélonomie. SociologieS [Online], URL: http://journals.openedition.org/sociologies/18924

Brown, A.L. (1992). Design experiments: Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2(2), pp.141-178.

De Decker, K. (2022). Can we make bicycles sustainable again? Low-tech Magazine, Feb. https://solar.lowtechmagazine.com/2023/02/can-we-make-bicycles-sustainable-again.html

Furness, Z. (2010). One Less Car: Bicycling and the politics of automobility. Temple University Press.

Illich I. (1973). Tools for conviviality. Calder & Boyars. https://arl.human.cornell.edu/linked%20docs/Illich_Tools_for_Conviviality.pdf

Jess, L. M. (2023). Degrowth and the slow travel movement: Opportunity for engagement or consumer fad? Tvergastein (special publication) 134-150. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f0f22180db4af1e7b139cf0/t/63d25e74f7cb98275c31ebce/1674731140813/Degrowth+Volume+2.pdf

Kropotkin, P. (1902). Mutual Aid, a factor of evolution. MacClure Phillips & Co. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/petr-kropotkin-mutual-aid-a-factor-of-evolution

Molsher, R. and Townsend, M., (2016). Improving wellbeing and environmental stewardship through volunteering in nature. EcoHealth, 13, pp.151-155.

Norcliffe, G. (2022). The cycling economy: An introduction. In Norcliffe G et al (eds.). The Routledge companion to cycling. Routledge. pp. 149-152.

Nurse, S. (2021) Cycle Zoo: Bikes for the 21st century. Silverbird Publishing.

Shannon, D. (2019) Anti-capitalism and libertarian political economy. In Levy, C. and Adams, M. S., (eds.) ThePalgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave. 91-106.

Wilbur, S. P. (2019) “Mutualism.” In Levy, C. and Adams, M. S., (eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave. 213-224.

Simon Batterbury is Associate Professor and at the Melbourne Climate Futures Academy, University of Melbourne and Visiting Professor, LEC, Lancaster University, UK. Simon has taught at universities in the UK, US, Denmark, Belgium and Australia over 30 years and works on environment & development issues in New Caledonia-Kanaky as well as on bikes in cities. His next book is Geography of New Caledonia-Kanaky (Springer, 2023, OA) edited with Matthias Kowasch. Board member of WeCycle, Northcote, Melbourne, volunteer in bike workshops since 2017. www.bikeworkshopsresearch.wordpress.com / www.simonbatterbury.net

Carlos Uxo is Senior Lecturer in European Languages at Monash University, and Board member of WeCycle, Northcote, Melbourne. He has a particular interest in Cuba, where resource constraints mean vélonomie is well developed. He has conducted research on initiatives to encourage cycling in Havana, and is preparing an article on the topic.

Stephen Nurse is a mechanical engineer and designer, author of The Cycle Zoo (2021). He is a Board member of WeCycle, Northcote, Melbourne and has worked at the Ceres and Back2Bikes workshops.

Dr Margot Abord de Chatillon is a French sociologist teaching at the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers de Paris, France. She is interested in bicycle repair, materialities and mobilities. Her recent PhD thesis (2022) dwells on the sociology of practices of bike repair in Melbourne and Lyon. She has worked as a workshop volunteer in both cities.

One thought on “On mutual bicycle aid”