An interview with Peter Singer

Peter Singer is one of Australia’s most influential and controversial public intellectuals. A moral philosopher and bioethicist, Peter is best known for his books Animal Liberation, a seminal text for the animal rights movement, and Practical Ethics, which explores why and how a living being’s interests should be valued.

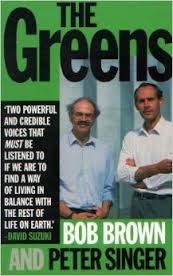

In 1996 Peter and Bob Brown published The Greens, the first book published in Australia setting out the political philosophy, policy framework and history of the Greens as a political party. Both Bob and Peter stood as Greens candidates for the Senate in 1996, the year Bob was first elected to the Senate.

Peter spoke to Green Agenda Editor, Clare Ozich, at the Progress Conference in Melbourne in May 2015. Peter gave a keynote address the conference on the ideas in his new book, The Most Good You Can Do: How effective altruism is changing ideas about living ethically.

The interview canvasses the notion of a green ethics as discussed in The Greens and its continuing relevance, the state of politics today both in Australia and the United States, effective altruism and its critiques, along with what it takes to be a public intellectual.

Transcript of Interview, conducted on 7 May 2015

Clare Ozich: Thank you Peter for speaking to Green Agenda. I would like to start by looking at the ideas in the book that you co-authored with Bob Brown in 1996, before moving on to your most recent book and the topic of your talk here at the Progress conference, Effective Altruism.

The Greens, the title of the book, remains one of the few books written about green politics and philosophy in Australia. When we were developing Green Agenda we saw the project in some ways as a continuation of that 1996 book. If you read it now, almost 20 years later, the issues haven’t changed much – protecting the environment, addressing climate change, the treatment of animals, money in politics, dodgy trade deals, the need for more progressive taxes, decent work, fair social security etc.

But along with usual list of issues, the book discussed what it calls Green Ethics. To quote “The revolutionary element in Green ethics is the challenge to see ourselves in universal terms. From an ethical perspective it is not the fact that I gain or lose by some action I am considering but that someone gains or loses”. The book goes on to talk about taking a long term view – making decisions for the future, not just the present.

What are your reflections on the formulation of Green ethics now and the challenge that worldview presents to our politics and political debate?

Peter Singer: I think that formulation of green ethics is still highly relevant. In fact one could say that with the climate change issue becoming more acute than in 1996 in that we haven’t made the changes that we really needed to make and should have made in those nearly 20 years, the fact that we are clearly going to have a significantly adverse affect on future generations just shows how important it is that we try to get beyond that immediate here and now and satisfaction of our personal needs and think about the impact we are having and give proper weight to the future, which we’ve not been doing. And also of course we’re still not giving proper weight to people in other countries who we could be doing a lot more to help as I talked about in today’s talk and who will be and already are being more adversely affected by climate change than we are.

In your talk you talked about the foreign aid budget and the situation here in Australia where both recent governments have cut the aid budget. They see it as a bit of a money box for other priorities, while you mentioned the UK and Canada have legislated the target of 0.7% of GNP and have met that. What do you see as some of the barriers here in Australian politics and public debate that makes that an acceptable position for both major parties to hold?

I think there has not been enough effort to get the public involved in understanding how little we are giving and how stingy that is by comparison with other countries, including the United Kingdom, in order to provide some political push for maintaining the original bi-partisan stance of increasing it. I think the original bi-partisan agreement was that we would get to at least half of one percent instead we are going away from it. I don’t quite know how to do it but clearly that’s what needs to be done. Political parties need to feel that there are people who will turned off from voting for them if they allow our foreign aid to sink to these levels. So far I don’t get the feeling that is really happening in Australia.

No, I don’t think it is. One of the other ways the book conceptualizes a green ethic is to consider the goal of increasing individual wealth, and describes that as part of the dominant ethic – I think it is fair to say it still is – and then looks to an alternative which is around providing for a community and preserving the environment. A distinction between individual self-interest and the broader interest. To quote the book: “The aim of accumulating the greatest possible amount of material riches is both individually irrational and collectively self-defeating” – leading to growing social inequality, and environmental destruction.

These ideas aren’t particularly new and this book was written 20 years ago and the Greens have been around for that long. But there are big barriers to seeing a realisation in our politics and broader community to taking on these values.

Yes there is always going to be something of a battle I think, because there is a conflict between peoples’ self interest and the larger community and universal values, so you have to expect something of a battle. But I think there are other countries that do it better where there is just more consensus on taking care of the community, where people understand better that that comes first and there will be a better society and we’ll all be better off if we actually do have more of that community focus rather than a self-interested focus. So I’m not sure, maybe we’ve been more influenced by the United States and less by Europe.

…we’ll all be better off if we actually do have more of that community focus rather than a self-interested focus.

Somebody said, you talked about the UK aid thing, but somebody else said to me recently they were looking at the UK election (somebody very concerned about climate change) and it is just a different sort of debate there because there was a consensus that there is an urgent need to do something significant about climate change and there really isn’t quite that consensus here unfortunately. Maybe some of these things depend on small things. Maybe if Malcolm Turnbull had been leader of the Liberal party instead of Tony Abbott that we would feel there was more consensus but certainly we don’t have it at the moment.

You stood as a candidate for the Greens back in 1996.

Twice, once for Kooyong in a by-election a couple of years earlier, when Peacock vacated the seat. Labor wasn’t standing so I actually got 28% of the vote which is not bad for the Greens. And then stood for the Senate in 1996.

You clearly saw value in the political process back then. It was a route to creating some of the change you want to see in the world. Your current book seems to query the value of that a little bit more. Correct me if I am wrong, but what do you think of the value of politics now? And I’d be interested to hear your reflections both in terms of Australia and the US.

I think it does vary with political systems. Since 1996 I have been living in the United States for quite a lot of that time, not all of it. To some extent, the book [The Most Good You Can Do] was originally delivered, or a version of it was delivered, as lectures at Yale, so it was more written for a US audience. The US political system seems to me to be to be more bogged down in hopeless partisanship than the Australian or most European political systems. Most other parliamentary systems do slightly better than the US. Also of course the importance of money in the US is vastly more rated than it is here, and getting worse. I do think for people in the US, the chances of making a difference politically are extremely small, not impossible but extremely small. Another factor is they have first past the post voting which is disastrous for attempts to form third parties.

It is different in Australia and if I was writing specifically for an Australian audience I would talk more about political challenges. There is tiny bit in the Australian edition of the book, the afterward, which mentions that. I do think it is important to be part of the political process and the Greens in Australia are a good example despite obviously not being as successful as we would have liked. A good example of having some positive influence and actually getting the carbon emissions trading scheme up and going even though it didn’t last long, unfortunately, was a significant achievement.

We’ll move on to your latest book “The most good you can do: how effective altruism is changing ideas about living ethically”. Can you give us a brief description of effective altruism?

Effective altruism is a philosophical outlook on how you want to live your life and it is an emerging social movement. The outlook on how you want to live your life is that with at least some of your resources, whether time or money or skills, you want to make the world a better place and you want to use evidence and reason to make sure that what you are doing is actually making the world a better place. In fact not just making it better but doing the most good you can with those resources. So effectively, effective altruists are trying to live their life in order to do the most good they can.

One of the examples you used in your book and that you referred to in your talk was a former student Matt Wage who made the decision not to continue with an academic career but to go and work in the finance industry. The thinking there being that he would earn a significant salary doing that work and therefore have more money to give altruistically. His calculation was that was the most good he could do. Going back to that previous quote I mentioned about green ethics where we talked about – “The aim of accumulating the greatest possible amount of material riches is both individually irrational and collectively self-defeating”. Are these ideas in conflict? How do they get resolved?

No I don’t think they are in conflict because Matt is not earning a lot of money in order to achieve the highest material standard of living that he can. He is earning a lot of money in order to be able to give away a lot of money and give it to causes that are actually doing a lot of good for people. So thinking carefully about which are the most effective choices to give to. He is actually using the ability money gives you to help to promote other causes and stands as an example against the idea that having a luxurious lifestyle, high consumer lifestyle is the right goal. He is saying “I am not living that, not because I couldn’t, not because I can’t earn enough to have luxuries but even though I do earn enough I am choosing not to live that way because I don’t think that is the most fulfilling or worthwhile kind of life.”

One of the more obvious critiques of effective altruism particularly from the perspective of people engaged in politics or broader social movements trying to change the world, is that it looks to treat the symptoms, and doesn’t look to the causes. It doesn’t take on the structural injustices at the heart of the suffering that people then seek to relieve. This is a long time argument against charity, or a critique of charity, that has existed for hundreds of years. The idea that the most good you can do is to reconstitute society so that poverty and other suffering is not possible and some people go so far as to suggest that altruistic values have prevented the carrying out of this aim. Zizek has made the critique of people like George Soros by saying that he repairs with the one hand what he ruins with the other.

What is your response to these critiques?

I think if we could make the larger changes it would dramatically reduce poverty. I don’t think it is worth talking about eliminating poverty altogether, that is really too utopian. But if we can dramatically reduce it we should try and make those changes certainly. But it has proven very difficult to do that for all of the efforts we have made, the alternatives to a capitalist global economic order seem less plausible today than they did 20 or 30 or 40 years ago.

the alternatives to a capitalist global economic order seem less plausible today than they did 20 or 30 or 40 years ago.

We could get some specific changes and I do work for some specific changes. I support efforts to make people more aware of the issue of taking resources from countries that are ruled by dictatorships where none of the economic dividends of those resources go to the people and they only go to the ruling elite. I think we could do something about that. We could maybe hope to stop the subsidising of agricultural products by the United States and Europe, which harms small peasant agricultural producers in developing countries. But beyond that it is really hard to see how we can make large-scale systemic changes. So that is why I think that it makes sense to focus on the more concrete specific things we can do. As to what you have said about Soros, you need to look at any particular case – is he really harming other or not and I am not going to make any particular comment about Soros. I don’t know enough about the details of what he has been doing. But I certainly don’t think that everybody who works in finance or investment is necessarily causing harm to others.

In your book you do talk about advocacy and you mention in particular the advocacy done by animal justice groups in relation to animals and food production. I think that you say that is an example where advocacy is the most good you can do.

To stop people consuming animals products and factory farm products. It is a strong candidate for that.

So advocacy isn’t completely out of the picture?

No, and I also talk about advocacy for the global poor and the example of Oxfam.

So advocacy is certainly in the mix. And yet if we take an issue like climate change – you responded to a question about that today as well – you are quite ambivalent in the book and on stage. The question there being that you are not convinced that change can happen or that advocacy can be effective. That is quite a confronting position for a lot of people working in the green movement.

I am not convinced that it will be effective but I do think it is worth trying. That is what I said in response to the question today. Because the payoff is so large even if the chances of success are small, it is still worth trying. Maybe this is a difference between 1996 and today – that the chances that we will avoid catastrophic climate change are clearly less today than they were or seemed to be in ’96. We’ve let the last 20 years go by basically and greenhouse gas emissions have risen and the time before we cross that threshold is too close now. But it is definitely still worth trying. I am not at all saying give up green politics because it is hopeless. I think we have got to keep trying as much as we can, even though we know the chances are small, it is so important that we can’t let it go.

We’ve let the last 20 years go by basically and greenhouse gas emissions have risen and the time before we cross that threshold is too close now.

One of the key elements of effective altruism is having an understanding of the probability that the change will have effect or the suffering will reduce. In the book you talk about organisations that evaluate charitable works. You talked about how this is a debate within effective altruism. Some groups that might evaluate quite stringently, other groups take a slightly broader approach. Is there a risk that this evaluation process leads to low risk activities rather than experimentation that could lead to bigger and better breakthroughs?

There certainly is such a risk. People in the movement are aware of that risk. Give Well is the example of the most rigorous but Give Well now has this thing called the [Open] Philanthropy Project where it is looking at a whole range of different causes which are high risk high return sort of causes and trying to get some handle on evaluating whether they are worth doing something about and high likely the payoff is and how big it would be. They have been supported in that by the Good Ventures Foundation, which has been one of their big backers. It is a foundation set up by one on the Facebook co-founders. So I think people in the movement are aware a lot of the focus has been on these smaller risk interventions and that that is not necessarily the only thing that is going to offer good value.

You talked in the talk and in the book about how effective altruism is becoming a movement. More and more people taking the decision to live their lives by these principles. We talk a lot about movements in the progressive movement. What is your thinking on this movement? Where is it coming from? Who is getting involved in it? How is it spreading and where do you see it going?

A lot of big questions. I think you have to say that it has not come out of any one place. Part of it has come out of philosophy, like Toby Ord and Will MacAskill, and that certainly been an influence is getting people to think about living their lives altruistically. But I think Holden Karnofsky and Ellie Hassenfeld played a crucial role in setting up Give Well and they didn’t come out of philosophy. They came out of hedge funds. But they were shocked by the lack of data you could get on charities. People are coming out of different angles. Other people have come out of the IT industry and so on. As I mentioned with Good Ventures part of the money going into this and also helping to support Give Well is coming out of people who have made quite a lot of money quite young and have thought about what they want to do with that. So that is roughly speaking where it has come from. But there are a lot of other different sources as well.

It is spreading because of the internet. I think that has also been critical to it spreading because people in different places could contact others and start talking about these things with them. Whilst they might not have known previously that there were other people that thought like this it would have taken longer. It is spreading on college campuses quite a lot. Where is it going – it is pretty hard to say. I don’t know. I hope that it is expanding and will gradually spread so that it becomes a major way of living your life and doing good in the world. But it is hard to predict how big it will become because it is growing quite well off a small base and that is easier to do so at what level it will start to plateau or the rate of growth will slow I can’t really predict.

Lee Lin Chin [moderated the Q&A with Peter at Progress] mentioned in one of her first questions to you that you didn’t mention politics once in your speech which was refreshing – not to have a speech bashing Abbott. It is the easiest thing to do in Australian politics at the moment. What do you see as the relationship between effective altruism and politics? Is there a relationship? Do they operate separately? Not everything has to be political.

It depends a bit on where you are. I would say in the United States not very much, pretty separately. It is not really part of mainstream democratic versus republican politics. Maybe that is slightly less true in other countries. I know that if you go to the 80 000 hours website there is some discussion about politics as a career. And there is a calculation of the odds that you will be able to get a seat in parliament, if you graduated from Oxford let’s say. If you look at who gets there it certainly seems to improve your chances. There is some discussion as to whether that is likely to be an effective altruistic career and how much good you can do if you do. I haven’t seen much of that in the United States. They are not necessarily opposed at all. I think EA’s [effective altruists] are aware that if you can influence politics you can make a bigger difference than you could out of your own resources.

Finally I wanted to talk to you about courage and public life. You are a controversial figure and have been for much if your career. I personally would like to see much more courage from our public intellectuals – whether I agree with them or not. What makes you prepared to be controversial? Has it had an impact on you and on your life?

I don’t think of myself as a particularly courageous person but I mean I suppose it turns out some people are more courageous about physical things, about which I am quite cowardly, and other people about other sorts of things. I took positions because I like to follow arguments where they go and I guess I was not afraid of challenging positions that seem to me to be not well rounded.

But I wasn’t very troubled about that because I thought the mainstream views were propped up by religious thinking that I didn’t share anyway.

Perhaps another factor is that I came of age in the late-60s and early-70s so when I started thinking about the treatment of animals that was a period where there was a lot of protest about the Vietnam War and racism and so on and I had experience in those movements here. As an undergraduate I was involved in the abortion law reform movement and the anti-Vietnam, anti-conscription movements. I don’t think they took a lot of courage. It was what a lot of other students were doing at the time. Then when I started thinking about the position of animals it seemed to me to be another sort of issue like this where people were assuming something morally which they were not justified in assuming. But because there were these other movements around to try and start a new one didn’t seem to me to require any particular courage.

Then when I started doing bio-ethics and my conclusions obviously had to work with the idea that just being a member of the species homo sapiens can’t be a crucial moral thing in itself. So that clearly led me to different views about the sanctity of life from those that were mainstream in the community. But I wasn’t very troubled about that because I thought the mainstream views were propped up by religious thinking that I didn’t share anyway. I didn’t think it took a lot of courage to take those views. It just seemed to me to be right. In fact I didn’t get a lot of flack for them for a few years. The flack really started building up when I was invited to give some talks in Germany and some of my works had been translated into German. I got a lot more heated opposition there than I got in Australia on those issues.

Presumably due to their own recent history?

Yeh – absolutely, which in a way is a good thing they are sensitive about that. But I think actually they took it the wrong way and used it as a reason for not allowing me to say things that I thought ought to be able to posed whether they agreed with it or not. Once you are in that situation and you have come to these conclusions I don’t think you can back away from them because some people are abusing you or shouting at you or even actually threatening you physically, which has certainly happened. I would say I got into this position more or less not very deliberately but got to a position where I felt I couldn’t do anything else but keep maintaining the views that I held. I think it would be good if more public intellectuals were prepared to say things that might make them unpopular. That’s true.

Thank you, Peter. I very much appreciate you talking to Green Agenda.