Culture is a wonderful word, isn’t it? It’s one of those words which means different things to different people and in different contexts, from opera to the microbes that turn milk into yoghurt.

For our purposes, the relevant definition from the Oxford English Dictionary is “[t]he ideas, customs, and social behaviour of a particular people or society”. American artistic activist Arlene Goldbard defines it more poetically as “the fabric of signs and symbols, customs and ceremonies, habitations, institutions, and much more that characterize and enable a specific human community to form and sustain itself.” ((Arlene Goldbard, The Culture of Possibility: Art, Artists and The Future (Waterlight Press, 2013), loc 113))

Culture is a magnificent, ever-changing mess of overlapping layers, with each of us belonging to many different aspects. We have ethnic cultures, socio-economic cultures and identity cultures. We have workplace cultures and family cultures. And we have the glorious interplay between them all that makes up national and global culture.

Culture drives the way we vote, the music we listen to, the way we deal with conflict and the way we make love.

Culture guides us as we make the myriad decisions that we make each day. Culture guides what we eat, whether we wear jeans, a skirt or laundered trousers, the words we use, the way we work and commute, how we engage with our children and our parents. Culture sits behind our desire to follow social mores or our willingness to break the law, whether by jay walking or shoplifting or locking on to mining equipment in an act of civil disobedience. Culture drives the way we vote, the music we listen to, the way we deal with conflict and the way we make love. And each of our actions feeds back on and influences culture as it continues to evolve.

We often forget that cultures change. Sometimes they’re changed by natural events such as earthquakes. Sometimes they are changed by disruptive technology like agriculture, iron tools or telecommunications. Sometimes they evolve incrementally as populations grow, pushing people into closer proximity, or as waves of migrants influence a host culture. Sometimes cultures are deliberately changed by a group of people adding intentional impulses to the bigger evolutionary process they form a small part of.

Culture can be benign, influencing whether we prefer eggs or congee for breakfast. But culture can become hegemonic, driving unhealthy consumption, blocking certain groups of people from access to services, limiting democratic choice.

Culture is at the heart of everything.

Culture and politics

What does this understanding of culture mean for how we do politics? It starts with this:

“Politics is the art of the possible”.

That old dictum used to be the bane of my existence. I would get deeply frustrated when people told me that it meant we couldn’t set targets for deep pollution cuts or 100% renewable energy. But, having extracted myself from day-to-day politics and spent time researching widely, discussing broadly and thinking deeply, I now believe it’s true – it’s just utterly misinterpreted.

If we accept the limits of what is currently possible – and the vast majority of our politicians, media, and environmental and social activists broadly do – we will never successfully face up to the deep challenges we face as a society, from preventing catastrophic climate disruption to building genuine social and economic equality to true Indigenous liberation.

But neither can we just baldly declare we are going to do the impossible. Within the confines of the existing socio-political culture, it is literally impossible.

Our job is to change what is possible.

And “what is possible” is fundamentally a cultural question, wrapped up in how we collectively and individually conceive of the world around us and our place in it. And culture changes all the time, and can be actively and deliberately changed through reprioritising cultural values, modelling different behavioural norms, and telling new culture-defining stories.

****

We need to acknowledge that we didn’t get here by accident.

The “right” has spent a generation redefining “what is possible” to suit their ends. Meanwhile, many of the “left” have ceded the ground on the basis of a failure to understand that “what is possible” is changeable. Thanks to that imbalance, the heterogeneous mesh of cultures that makes up any society has come to be dominated to an extraordinary extent by one world view – a materialist, consumerist, individualist world-view, permeated by values of wealth and status, subjugating and pushing to the margins values of community, compassion and care for the environment. Subcultures are still expressed through minority voices, but the governments we are able to elect and the policies we are able to implement, even the stories we can get reported, are limited by what that narrow culture deems “possible”.

Consequently, working to phase out coal or abolish tax breaks for the rich or close the gap or any other deep change from within the dominant culture, without attempting to change the culture, is doomed to fail.

The clearest articulation of this I have seen is from American activist, Daniel Hunter: “Politicians are like a balloon tied to a rock. If we swat at them, they may sway to the left or the right. But, tied down, they can only go so far. Instead of batting at them, we should move the rock.” ((Daniel Hunter, Strategy and Soul: A Campaigner’s Tale of Fighting BIllionnaires, Corrupt Officials, and Philadelphia Casinos, Smashwords, 2013, Chapter 10)) I would expand that to say it’s not just politicians – it’s all decision-makers. And we all make decisions. We are all balloons tied to the rock of our culture. To build power and truly create change, we have to move the rock.

Culture and power

Culture has long been seen as critical to social and political change and control. Its role has been instinctively understood by many rulers and change-makers since time immemorial, but it was in the 20th century that political science began to grapple with it.

The central concept is that culture, by framing the way we understand our world and our place in it, by limiting or expanding our social and political discourse, consequently underlies and circumscribes our behaviour. As Goldbard expresses it, “our capacity to act is conditioned on the story we tell ourselves about our own predicament and capabilities.” ((Arlene Goldbard, The Culture of Possibility: Art, Artists and The Future, Waterlight Press, 2013, loc 193.))

In societies where force is not the primary means of social control, cultural power is what replaces it. Antonio Gramsci, for example, considered culture central to his conception of hegemony. He developed Marx’s theory of class dominance to cover a critical point of power dynamics – that those in power will seize control of the arena of ideas as much as they will the traditional arms of coercive power. Power is held by controlling the discourse, and the deepest way to contest power is to contest those ideas at the cultural level.

Noam Chomsky writes that power is held over us only with our consent, and powerholders actively manipulate and ‘manufacture’ consent.

In writing that “[t]he smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum,” ((Noam Chomsky, The Common Good, Odonian Press, 1998, 43.)) Chomsky could have been describing ABC’s QandA.

Naomi Klein flips the perspective and argues that “if there is a reason for social movements to exist, it is not to accept dominant values as fixed and unchangeable but to offer other ways to live – to wage, and win, a battle of cultural worldviews.” ((Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything, Allen Lane, 2014, 61.))

As a fascinating aside, many climate scientists are way ahead of campaigners in recognising that culture is key to climate change, driving the social norms that create it and holding back the necessary social, political and economic change to address it.

Climate scientist, Kevin Anderson, quoted in the RSA’s A New Agenda on Climate Change, says that the numbers are so stark that what we have to do is “develop a different mind-set – and quickly.” ((Rowson, Jonathan, A New Agenda on Climate Change: Facing up to Stealth Denial and Winding Down on Fossil Fuels, A report for The RSA, December 2013, 18.)) Similarly, Former Director of CSIRO’s Division of Atmospheric Research, Professor Graeme Pearman, told my research that “Climate change is really a human question, it’s not primarily a physical science question at all. It’s about what humans perceive they want or need.”

I really like how the RSA explores that idea:

“[E]nergy demand is driven by perceived ‘need’, but this sense of need is highly contingent from a historical or cultural perspective. Global perception of energy demand is driven by the social practices … we come to view as normal (eg two hot showers a day, driving short distances, regular flying), features of life relating to contingent norms of cleanliness, comfort and convenience rather than inherent features of human welfare.” ((Rowson, Jonathan, A New Agenda on Climate Change: Facing up to Stealth Denial and Winding Down on Fossil Fuels, A report for The RSA, December 2013, 25.))

If what we perceive to be necessary in our lives is culturally driven, then any solutions must also grapple with culture and seek to change it.

****

It is no accident that culture has artistic connotations as well as deep political meanings. If culture is about our understanding of our world and where we belong in it, art is one of the first and best ways in. Art is how we make sense of our world and how we find our place in it. Art, including music, is one of the earliest human impulses. Actually it predates humanity, and is found in many other species, from mating calls to territorial marking to group bonding. Musical instruments are some of the earliest discovered tools, found in some of the oldest archaeological digs.

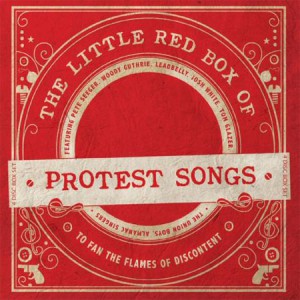

This instinct for music as a way of finding and cementing our place in the world developed into hymns and other religious music, ethnic musics which still bind many of us so deeply, national anthems, and protest songs.

One of the early deliberate attempts to create change using artists was taken by union organisers in the USA, bringing in musicians to recruit supporters. Most famously, the Industrial Workers of the World, better known as the Wobblies, saw folk music as central to their project, publishing their Little Red Songbook with regular updates throughout the last century, and directly inspiring songwriters such as Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. Later, the Highlander Centre, one of the first activist training centres in the world, involved a substantial focus on music, recruiting and training musicians and workshopping campaign songs. “We Shall Overcome” is the most famous of many protest songs of the 1960s that had its origins there. Spirituals and blues became a key part of the fight for civil rights in the USA just as Jimmy Little, Yothu Yindi and many others made their art a part of their fight for Indigenous self-determination here in Australia.

A clear lesson from history is that not only can artists play a pivotal role in social change, but that such change is unlikely to occur unless cultural processes are at play, because social change is cultural change. The ability of arts and artists to draw people together around a new conception of the world is second to none – and without such a shift, change will not come.

“Identity processes are inherent in all movements,” Rob Rosenthal and Richard Flacks explain in their excellent book Playing for Change, “[a]nd music is the way many first try on that identity… Indeed, music is a major resource for identity construction in contexts that are remote from the political”. ((Rob Rosenthal and Richard Flacks, Playing for Change: Music and Musicians in the Service of Social Movements (Paradigm Publishers, 2012), 165.))

Possibly one of the most powerful tools for social and cultural change, then, is the ability of artistic work infused with that sense of identity to spread ideas wider. As Rosenthal and Flacks say:

“What begins percolating isn’t a coherent ideology, but… “structures of feelings”, part emotional, part rational, a heady brew of social ideas, fashions, music, and so forth, both precursor to a developing ideology and more than simply an ideology, involving “meanings and values as they are actively lived and felt” by each individual.” ((Rob Rosenthal and Richard Flacks, Playing for Change: Music and Musicians in the Service of Social Movements (Paradigm Publishers, 2012), 100.))

Eyerman and Jamison, in their seminal work Music and Social Movements, describe the interaction between arts and social change activism as a “source of cultural transformation”:

“[B]y combining culture and politics, social movements serve to reconstitute both, providing a broader political and historical context for cultural expression, and offering, in turn, the resources of culture – traditions, music, artistic expression – to the action repertoires of political struggle.”

This concept of art and social movements becoming a melting pot in which we reconstitute our broad culture to create deep change has deep resonances beyond the specifically ‘artistic’. It brings to the surface the point that, in order to achieve the change necessary to prevent climate catastrophe, we need to address issues that lie very deep indeed – at the level of culture.

I dug into this question through a series of interviews undertaken as part of my research in establishing Green Music Australia. Guy Abrahams, CEO of CLIMARTE, reflected:

“Most of the time we’re not even aware that we’re enmeshed in a cultural fabric that is… both persuasive and sometimes restrictive in terms of where we think we can go. And so if you can move that net, move along that net, or put in new threads, that’s when you give people the opportunity to move along.”

Graeme Pearman, told me: “For each of us, the vast majority of our understanding of how the word is is based on culture, is based on religion, is based on hearsay. These are story lines that are very powerful and hard to move.” As Anna Rose, co-founder of the Australian Youth Climate Coalition, says, “[c]ulture is so crucial… in shaping the way people think about things, and normalising certain ways of being and certain ways of thinking.” Culture, says Tipping Point Australia’s Angharad Wynne-Jones, is “where change happens.”

In this conception of the term, culture is the key to social control and change.

****

If culture is central to power, what are the implications of that for how our movement currently works to build power?

Firstly, it is not to say that campaigns focused on community organising and mobilising aren’t crucial in building power. Rather it is to argue that we cannot mobilise people effectively for long term change if we do not engage at the level of culture. We may win individual local campaigns, but we cannot create the deep change we need to tackle the deep crises of our current era unless we use mobilisation to challenge, undermine and replace the dominant culture.

Equally, it is not to say that engaging with day to day politics is pointless. Rather it is to contend that culture is central to enabling or blocking law reform because culture restricts or expands the terms of our political debate. Engaging in politics in a way which emphasises or buttresses the existing culture may win in the short-term, but will damage our long-term interests.

Finally, this is not to deny the reality of economic power and the barriers to action it creates. Rather it is to question whether that power is held primarily through structures and institutions or through culture. We can seize power back from those who currently hold it to our detriment, but most of the time most of us choose not to even try.

Why not?

Rather it is to question whether that power is held primarily through structures and institutions or through culture.

While the dominance of the current culture persists, none of the individuals involved – political or business leaders, journalists and editors, ordinary citizens – are able to envision a reality outside it. We know this from theory, but also from practice. We are all used to hearing phrases like “but we can’t do that, it would mean a different world”, or “that’s not how we do things”, or “politics is the art of the possible”.

Consider that this same culture has a strong hold on all of us. Not just those of us we’re campaigning on. Us too. We all tend to live our lives as though nothing will change. Having children, putting money into super funds, buying property – none of this makes sense, given what we know about the climate crisis.

****

I argue that those in power have shaped contemporary culture as an aedifice which supports them, and they hold on to it with every ounce of their strength. Subcultures are not allowed access to the mainstream – witness everything from The Australian’s stated aim to “destroy the Greens at the ballot box” to Tony Jones’ contention that a protest disrupting #QandA was not a legitimate democratic expression.

This is not to suggest some Illuminati-style conspiracy. Rather it is to say that, through some two millennia and more, power holders have consistently manipulated the discourse to suit their interests. There have been ebbs and flows in this tide, but I see a progression from the Ancient Greek separation of “man” from “nature”, through the Enlightenment’s ideal of the rational “homo economicus”, via the colonial frontier notion that the Earth’s vast bounty is ours for the taking, into the baby boom’s cementing of materialism, all leading to Francis Fukuyama’s “End of History”, Margaret Thatcher’s declaration that there is “no such thing as society”, and what Naomi Klein calls “triumphal capitalism”.

Much of this was a slow evolutionary process, with the intentional impetuses of those in power manipulating circumstances that technological and population change were already creating. But aspects of it, particularly in the decades following World War II, were part of a very deliberate “culture war”, waged by the right in order to embed their political agenda so deeply that it became difficult to shift.

At the heart of this post-war strategy was Friedrich von Hayek’s Mont Pelerin society. These right wing economists, shut out of mainstream debate in the 1940s by the dominance of Keynesianism, very deliberately set about a process of cultural change. Leveraging the support of wealthy businessmen, they created bulkheads in academia, in the media, and in politics from which to prosecute their case, enter the debate, and eventually dominate the discourse. It was their effort which brought psychological skills and insights to advertising. It was their actions which served as the template for both Rupert Murdoch and the Koch Brothers’ exercise of power.

Hayek’s work is in no small part responsible for creating our current culture. But it also points to how we can change culture again and make another world possible.

Values, narrative, behaviour and culture

Before we change culture, it is vital to understand the key drivers of culture, and that is primarily a question of values.

Values are central to culture as it is largely through values (and the stories and behaviours that embed them in our consciousness) that we establish our conception of the world and our place in it. Do we prioritise personal wealth or generosity; status or fairness; hedonistic pleasure, creativity, compassion or care for the environment? And how do these values interact and guide the decisions we make?

In mainstream society, for example, virtually everything we do directs us towards the value-laden belief that consumption drives happiness. Our media is filled with ads urging us to consume more; our shopping centres are designed to make us buy more (things we didn’t come to buy); our news bulletins always include market reports; perhaps most fundamentally, we are referred to as consumers far more often than as citizens or people.

The story of modern life has become the story of consumption. It has attained the power of a creation myth.

This is a prime example of how values embed certain behaviours and practices in our culture, how narratives develop to cement those values in place, and how behaviour in turn entrenches the culture. But how does it work?

We’ve known for a long time that values are at the heart of politics and campaigning. If we haven’t learnt this from theory, we should have picked it up from the success of right wing values politics, not just in winning elections but in dragging our entire polity to the right. We should have recognised how anti-environmental commentators such as Andrew Bolt, Miranda Devine and The Australian’s editorial writers consciously use values and cultural norms to their advantage. They deliberately portray concern for the environment as a “luxury of the rich”, as contrary to “more important” needs, and ridicule those who express such concern as outside the norm.

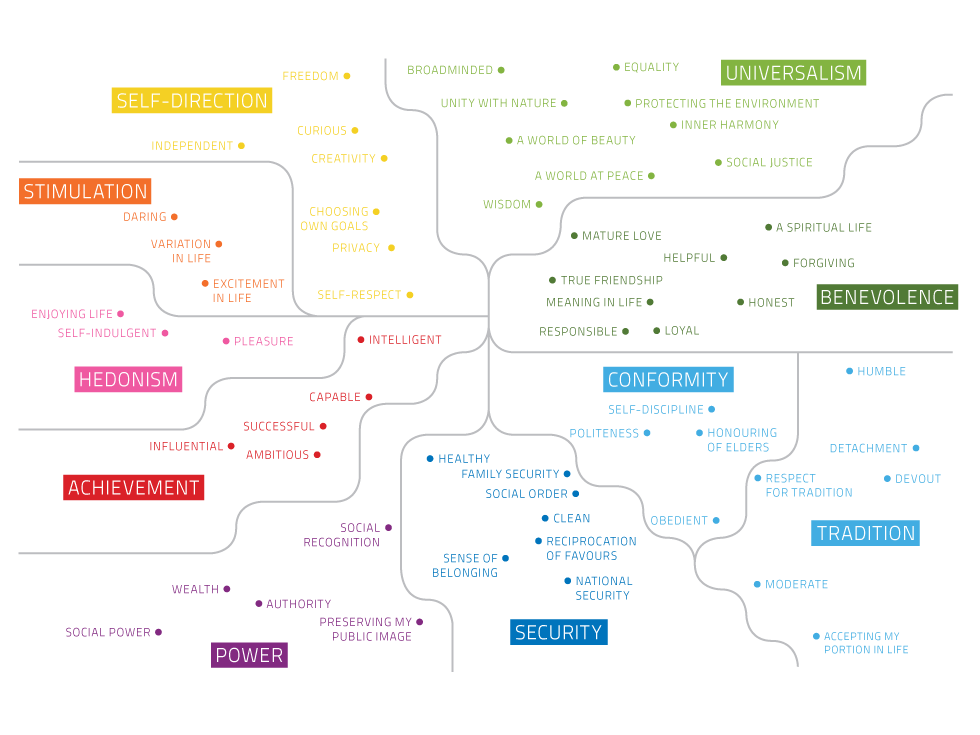

The most sophisticated work going on in this area, in my opinion, is the research undertaken by the Common Cause project. Here, psychologists involved in values mapping – analysing the way values relate to each other in our minds – have shown that emphasising “extrinsic values” such as wealth, status and security undermines and suppresses “intrinsic values” of sustainability, compassion, creativity and universalism, and vice versa.

Consider what that means for our society, where we are constantly bombarded with advertising and financial reporting, being addressed as consumers and shoppers, with our governments and corporations focussed on popularity polls and profits. How can we hope that people will actively support a carbon tax, or even a renewable energy target, when they are constantly being told that wealth and status today must be prioritised over everything else?

Culture is often established through narratives, from creation myths to fairy tales, which embed values and norms.

We need to tell a new story. And we need that story to be so compelling that it trumps and subordinates the existing story of modern life.

In order to change culture, we first need to identify the narratives that underpin our current culture.

This is, of course, very much up for debate, but I suggest the following:

“It’s the economy, stupid”

That we can consume our way to happiness. That greed is good. That everything can be boiled down to money and the economy.

“Me, myself and I”

That there is no such thing as society. That hyper-individualism is king. That if every person is enabled to seek their own benefits, everything will work out for the best.

“Human dominance”

That the Earth and all its creatures and resources are “man’s dominion” (from a one-eyed reading of the Bible), there for us to make use of as we please.

“This is just the way it is”

That change is impossible. That politics is the art of the possible, so we have to adjust our goals to match what is currently possible.

These four cultural narratives emphasise values of wealth, status, material possessions, and a narrowing of the value of security to the smallest scale – protecting me, my family, my culturally homogenous white bread country, and excluding the broader conception of security as a universalist need for us all to work together to learn to share this tiny planet.

Put these four value-laden stories together and you find out why we are not tackling climate change, why we accept dehumanising brutalisation of refugees, why we desert public schooling, why we no longer join unions, why we fail to face up to our past and present mistreatment of Indigenous Australians, and so much more.

Here is my attempt at creating a new set of stories to replace those four cultural drivers:

“Can’t buy me love.”

Readdressing what makes us happy is at the heart of it. We need to demonstrate through modelled behaviour, through experiential programs and through new stories, that consumption and materialism do not make us happy. There is reason to believe that if some of us stopped campaigning for climate action and started campaigning towards greater happiness, we might be more successful.

Critical aspects of this are limiting advertising, especially in public spaces, refusing to be called “consumers”, and getting off the treadmill.

“We are one, we are many”

To overcome hyper-individualism, we need to rebuild the power of community as stronger than the individual, through modelling, story and experience.

There are important cultural processes in this realm already underway, sometimes referred to as the empathy revolution and the sharing revolution.

“Living on a pale blue dot”

We need to rebuild a culture that understands that human civilisation is one small part of, and entirely dependent upon, the natural world. We need to rekindle our sense of wonder, rediscover our humility.

An obvious part of this is to heal the nature deficit that Richard Louv and others have written about.

Another aspect is to embrace the biomedical understanding that each of us is, in fact, an ecosystem, rather than an individual member of an individual species! We have an entire biome within and surrounding ourselves, living in our guts and on our skin, sustaining us as we sustain it.

A third is to tell the powerful stories of how ecosystems work, not just tales of collapse but also of re-wilding. George Monbiot’s beautiful description of how wolves heal rivers is a perfect example of this.

“Change or be changed”

In order to move from a culture of stasis to a culture of transition, we need to tell stories that explain that “change is coming – whether it’s positive or negative change is our choice”.

Individual experience is central to this process – the idea of “being the change”.

****

Narrative is, of course, not just about telling stories. Often narratives are conveyed, and values embedded, through behaviour. Personal experiences, empathic encounters, immersive experiences and modelled behaviour are very powerful ways to embed new narratives and reprioritise cultural norms.

Climate communications expert, Susanne Moser, focusses on behaviour in discussing the goal of “bring[ing] about changes in social norms and cultural values”. As she notes:

“through efforts to influence behavior not just situationally, but fundamentally—via early education, effective interventions later in life, and pervasive modelling of certain behavioral norms—it is possible to set new or change existing social norms, portray less consumption-oriented, energy-intensive lifestyles, promote new values and ideals around family size and reproduction, and lay a foundation for broad acceptance of policy interventions…” ((Susanne Moser, ‘Communicating Climate Change: History, Challenges, Process and Future Directions’ (2010) 1(1) Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 53, 38.))

Moser notes that, where narrative can be seen as an externally imposed driver, leadership by example and behaviour change are most effective when interactive, enabling a deeper engagement with the issues.

Supportive, if not essential, here are dialogic forms of interaction, which can be used to involve audiences in shaping the new lifestyles and visions of a more sustainable society rather than simply ‘deliver’ them from some external, higher authority to the public for implementation.

So, how do we put these theories and ideas into practice?

“Changing what is possible”

If we understand the political, social and ecological situation we find ourselves in as a cultural phenomenon rather than purely an economic one;

If we understand power as exercised through culture, and our capacity to act as mediated and limited by culture;

If we see cultural narratives embedded into our world through news and entertainment media and the narrowing of political discourse, through advertising, through urban design, through public policy decisions made incrementally so as to be less obtrusive, and much more;

Then we find ourselves at a moment of astonishing opportunity.

Right now, with the collapse of confidence in politics, with the collapse in news media consumption, with the rise of the internet and social media, and with over-reach by governments, the whole aedifice is at risk of collapse.

If we now systematically and systemically seek to reprioritise cultural values, model different behavioural norms, and tell new culture-defining stories, we can, as Naomi Klein calls us to do, Change Everything.

So what will this entail?

Much of the task will simply be about challenging ourselves to ensure that our campaigns, outreach and communications are helping to create a culture more conducive to caring for the environment, rather than buttressing the old culture. But we should also look to new ways of leading by example, creating experiences, involving people in participatory processes.

There are numerous models which can be brought in as tools in the broader movement for climate action if we embrace the need for deep cultural change. Some are well-understood ideas that take on new importance through this understanding of cultural politics – ideas like downshifting and reducing working hours; replacing Gross Domestic Product as our measure of national success; introducing new governance models around bioregionalism, worker owned cooperatives and deliberative and participatory democracy.

Some fantastic thinking is going on at the moment, bringing together suites of ideas like these into new systemic proposals by groups like the New Economics Foundation. I would go deeper than some of these, such as The Next System, launched in the USA in March, which still frames the world around ideas of ownership and exchange instead of social interaction and ecology. If we are to achieve deep change, that too must shift.

A number of ideas mentioned in the section on new narratives above deserve more exploration.

One of the most promising is the identification of and response to what Richard Louv describes as Nature Deficit Disorder. ((Richard Louv, Last Child in the Woods, (Algonquin Books, 2005), 335.)) The fact that we are bringing up generations of children who have less and less direct experience of playing in nature has serious implications for how we understand our relationship with nature. How can we love nature, how can we fear and mourn its loss, if we have no direct experience of it? Fascinatingly, it goes a lot deeper than this. Louv points to medical and psychological research attributing all sorts of problems to a lack of connection with the natural world, from obesity to depression.

There are now several organisations, including Nature Play, Natural Change, and Project Wild Thing, dedicated to driving broad cultural change through engaging children and adults with nature. Through modelling and immersive experience, these projects can make a significant contribution to the fourth thread of narratives above – the story that our society is a small part of, and entirely dependent on, the natural world – and shifting deep cultural values expressing our place in the world.

Alongside this thread is the recognition that, as a society, we are losing our vocabulary of the natural world. This discussion was triggered by a decision by a British publisher of a children’s dictionary to remove “blackberry” the fruit but include “Blackberry” the communications device. There is now an active movement to reclaim old vocabularies, driven by the recognition that, if we cannot describe the natural world we cannot truly value it.

The development of the sharing economy is also an important part of the picture. And I do not mean the peer-to-peer rental economy of Uber, Airbnb and others. More radical versions such as the Buy Nothing Project, where people offer things to others in their local community to use or take, and ask for goods and services they need, go far deeper. Ideas such as mini free libraries and recreating commons with community orchards and gardens similarly build a more interconnected, mutually supportive world.

Connected to sharing rather than consuming is the reinvigoration of repair. Free bicycle repair workshops have been springing up, as have “repair cafes”, where you can go to learn skills for fixing damaged goods rather than throwing them out and buying new ones. Practical workshops around installing insulation or establishing garden beds are another way to embed values of community and ecology and tell new world-describing stories through active behaviour change.

Taking on advertising will be crucial. Tim Kasser and the Common Cause project have demonstrated a clear link between advertising and suppression of intrinsic values because advertising boosts extrinsic values such as wealth and status. Working to limit advertising, through regulation of public space, restricting advertising targeting children, civil disobedience campaigns against public space advertising and more, will be a vital part of addressing climate change culture.

The concept behind Green Music Australia is that, if we musicians can start to convincingly walk the talk, if we can green up our own industry through cutting waste streams, by using LED stage lights, efficient refrigeration, and on site renewable energy, and by tackling transport to and from gigs, we can become very powerful cultural leaders. By tying together modelling of behaviour, experience and participation, both for the musicians themselves and for their surrounding industry and audience, and the cultural power of the music itself, the idea is that this will drive change at a deeper level than has yet been achieved by the environment movement.

Bringing these threads together is a most fascinating idea, filled with opportunity for the role of the arts in driving climate action. That is contained in a recent paper published by Common Cause suggesting that engagement in arts & culture in and of itself can encourage values of compassion, social justice, and sustainability.

The value of care for the environment sits on the map close to values of creativity and curiosity, amongst the values collectively referred to as “intrinsic”, and opposite “extrinsic” values, such as desire for more material possessions, social status and power.

“If we accept the sensible proposition that engagement in arts and culture activates values such as “curiosity” and “creativity,” then the implication from the research … would be that the intrinsic portion of the human motivational system could be encouraged and strengthened, while the extrinsic portion could be suppressed, as a result of participating in arts and cultural activities… As such, it may be that the more that one engages in artistic activity for these kinds of intrinsic reasons, the more the intrinsic portion of the motivational system will be strengthened, and thus the weaker extrinsic values will become.” ((Professor Tim Kasser, in Mission Models Money & Common Cause, The Art of Life: Understanding How Participation in Arts and Culture Can Affect our Values (2013) 10-11.))

It may well be that, beyond their role in helping to most effectively communicate messages and support social movements for change, the arts may in and of themselves change our culture to one more conducive to tackling the climate crisis.

****

There is more research to be done in this area to confirm the link in practice. Indeed all of these ideas are yet to be demonstrated.

But what I believe is beyond doubt is that, if we continue to attempt to solve the ecological, social and political crises we face from within the current socio-political culture, we are attempting to do the impossible.

It’s time we changed what is possible.

For further discussion on the ideas presented in this essay, see the following responses: